Dear Gemba Coach,

If it works, why worry if it’s called lean, operational excellence, or the company’s excellence system? As long as we get results, what does it matter?

Of course, it matters. Let’s go to the gemba and consider the one question I wait for – and rarely hear: “Which book should I start with?”

That’s how most of the transformative lean leaders I know started their journey – by reading a book (often Lean Thinking or The Toyota Way). Sure it sounds self-serving for an author, but there you have it. Curiosity and seriousness are probably the two most important qualities to look in a would-be lean leader. They want to succeed. They read around to figure out how to do it.

What I’ve learned – the hard way – over the years is that lean is a people development system, not just a production system. And indeed, this starts with understanding talent: looking for it, supporting it.

On the gemba, people are challenged to show their improvement topics, to explain what problems they’re working on, and to detail the logic of their thinking. Most get defensive as they’re pushed out of their comfort zones, and no matter how careful you are, and how hard you listen to their point of views, you need the conversation. But some are cool with discussing problems and assumptions and want to know more. So they ask: where should I start?

This is precisely the signs of curiosity and inquisitiveness we are looking for.

What’s in a Name? A Lot

Now, assuming that many more people will wonder about what we’re doing but not necessarily think of asking (or dare) in the situation, they might still wonder: what book should I read; where can I learn more about this?

At this crucial step, the name of the approach matters enormously because it orients inquiry. Operational excellence, for instance, will orient the curious mind towards tools, tools, and tools to reduce costs by eliminating waste. Six sigma (thankfully not mentioned so often these days) will point towards eliminating variation in the process – regardless of purpose or outcomes.

“Lean,” on the other hand, will orient people toward a confusing amount of stuff, but with some luck, people can start with the classics and move on from there. They can get onto the Lean Post, or Planet-Lean and discover current thinking about lean. Certainly, there is no consensus and lean has attracted its fair share of haters and misrepresenters over the years, but overall there are so many good examples published, as well as so many solid works that chances are they’ll stumble on a good starting place.

Considering that dedicated readers will go through about ten books a year, the first three really, really matter to forge an initial opinion and start structuring the thinking. Consider the two different paths:

- Okay, this is the usual continuous improvement to cut costs in every process,

- Wow, what do they mean by customer value and people development?

We’re in two completely different mental spaces, and as a result, two completely different inquiry processes.

Go the Thinking Way

We’re back to deep assumptions in lean: results can be good or bad depending on the quality (and repeatability) of the process to achieve them. Good results without a good process reflect luck, which is really nice to have, but not that much of a step forward in lean terms because we haven’t learned anything that we can try at another time or in another situation.

One thing we’ve finally understood from studying visual management and people development in Toyota’s way of doing things is to switch from command-and-control to orient-and-learn-by-doing.

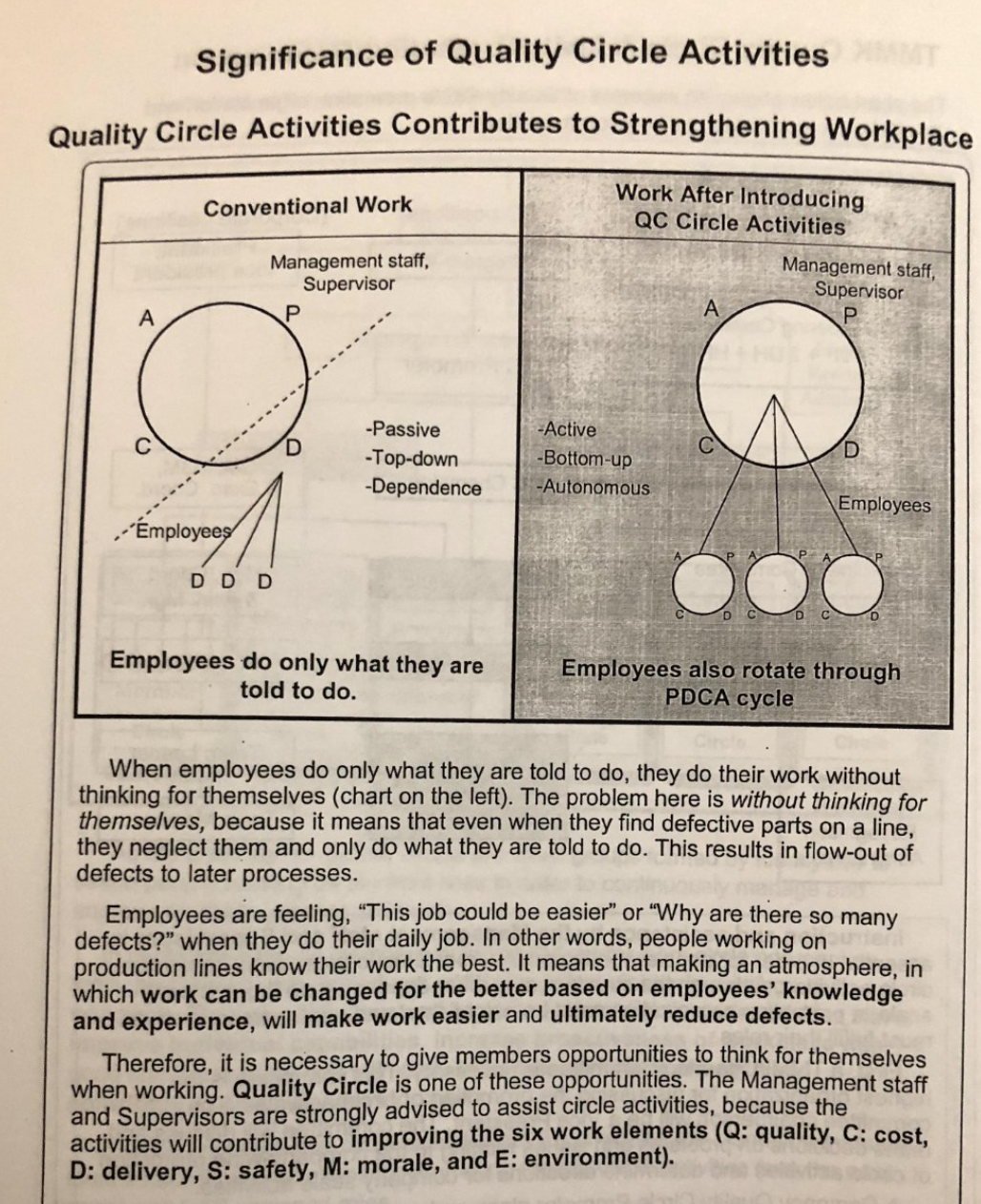

Tracey Richardson, Toyota veteran and co-author of The Toyota Engagement Equation, recently shared a page from the quality circle manual she was trained with as a group leader:

The aim of lean activities is explicitly to “give members opportunities to think for themselves when working.” This is so widely different from most management approaches rooted in the belief that bosses think and workers do, that it takes an effort to fully integrate it into one’s own thinking. This is what makes “real” lean so different from any other approach out there. Improvement activities are not aimed to just fix stuff, but to make people think so that they understand better what they do, feel greater responsibility, produce higher quality more productively and, in the end, make work easier and reduce defects by changing things based on their knowledge and experience.

Calling lean “lean,” if lean is what you’re after makes tremendous sense as it orients the whole endeavor and where people look to learn more on their own. Debating what “lean” means also is not just arid and meaningless philosophizing remote from the gemba, but essential to determine the direction of the endeavor and give signposts for everyone to know which way to go autonomously. “Would you tell me please,” asks Alice, “which way ought I go from here?” “That depends a great deal,” answers the cat, “on where you want to get to.”