Dear Gemba Coach,

Does respect for humanity mean the same as respect for people? I hear that the literal translation of the Japanese phrase “respect for people” is really respect for “humanness” – whatever that means?

I honestly don’t know, but it’s a very interesting point. I don’t know a word of Japanese, but Jon Miller, who does, makes a similar point here: He says the original Toyota phrase really means “holding precious what it is to be human.”

Assumptions are always so easy to make, in particular with assumptions on underlying theories. Our Western approach to organizing work is deeply steeped in the desire to turn human beings into robots. We keep thinking that humans are fallible in a way systems are not – human error. Modern organizational thinking started with Frederick II of Prussia who beat the hell out of his neighbors by creating the first modern army, transforming haphazard regiments of condemned criminal and aristocratic officers into obedient automatons, inventing much of the bureaucratic concepts we now take for granted, such as rules, roles, uniforms, controls, etc.

Respect for people doesn’t start with challenging others – it starts with challenging ourselves.Adam Smith and Max Weber codified this system by showing that (1) work could be broken down into smaller and smaller specialisms and that (2) very large organizations could be run as “rational” bureaucracies by requiring individuals to play impersonal and dispassionate “roles” – the perfect grey civil servant (to oppose the arbitrary, colorful aristocrat). Frederick Taylor perfected the system by having experts minutely optimize the working rules and create incentive systems to persuade workers to conform. From the mid-sixties, these techniques that had so far been applied to blue-collar workers spread to white-collar workers as computer systems could now regulate everyone’s work. (In the lean movement, we see traces of such thinking in ideas such as “leader standard work” and so on.)

In this context, respect in the usual sense of the word is a real concern. Indeed, the very system is brutally disrespectful as it forces human beings to behave like machines: passionless, repetitive, mechanical. Not surprisingly, such organizations take all meaning out of work by taking people for granted and forcing onto them mindless tasks, disconnected from their values and day-to-day problems, which overrides their everyday judgment and demands they have no supportive relationship at work. Of course “respect” is an issue, considering what the Taylorist/bureaucratic system demands of a person in exchange for employment.

Core Concept of Lean

On the other hand, this is very much the reflection of the Western organizational tradition (with its corresponding dream of abandoning all forms of organization and returning to craftsmanship as if it were better, sort of the heroic fantasy of the working world). Industrial firms in Japan did pick up many of these traits, but, certainly in the early days at Toyota, they, from the start, valued humans over machines. The goal of early jidoka was to make machines more human-like, not humans more machine-like. These engineers understood that, first, only humans could really master any operation and (as well as because) only humans could be creative.

To this day, Toyota cultivates a few operators that make parts by hand who continue to perfect their craft, for engineers to draw their inspiration from them when designing new generations of machines. Sharpening manual craft is seen as the key to smart automation. Indeed, the idea when automating is not just to reduce the work burden with machines, but indeed to have machines stop and identify what the problem is.

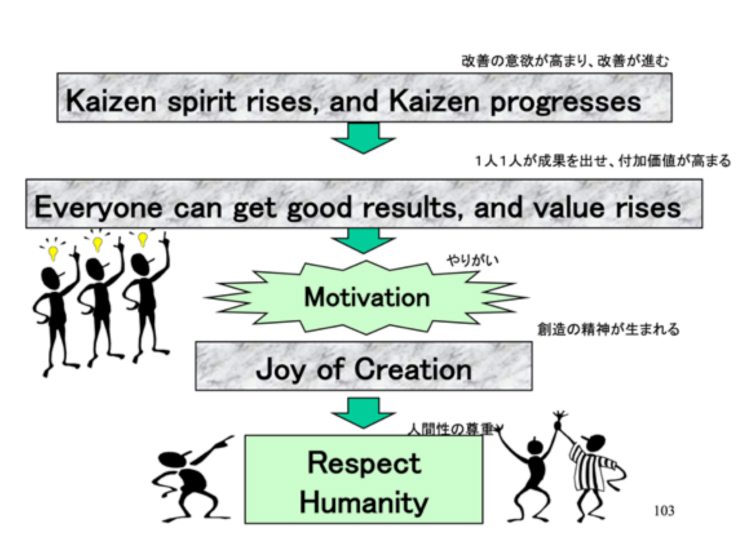

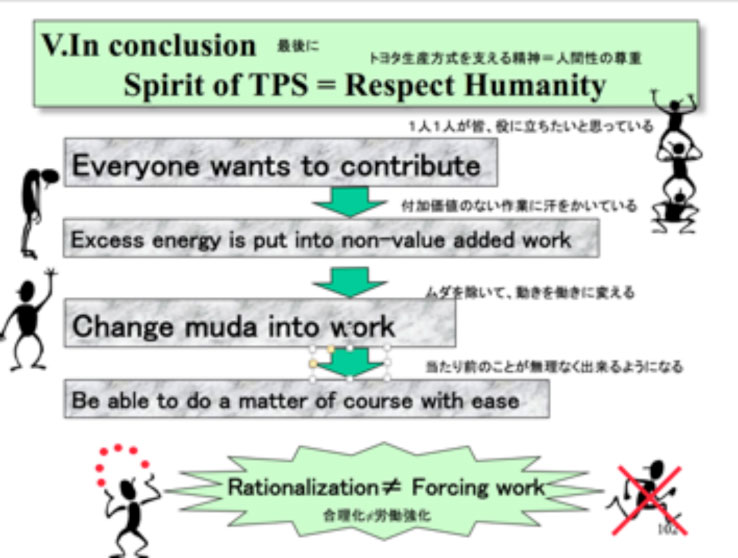

Kaizen, or the opportunity for humans to be creative and display this creativity, is the core concept of lean’s entire managerial approach. The two following Toyota slides from my father’s sensei describe the reasoning about human resources:

If we take this at face value, it does change radically how we can think about “respect for people.” The management imperative is to create an environment where people can be creative and truly enjoy their work.

What Humans Need

Interestingly, this is also a question the high profile tech companies such as Google, Facebook, etc. are asking themselves. Rather than work with tradition, they attack the problem by pouring over the reams of data they have about performance, and although it is very, very hard to generalize about human performance, some common themes are appearing. To work serenely and productively, humans seem to need:

- Clear line of sight: Understand the purpose of work by the leader and fundamentally agree that this purpose fits with one’s own values (not being asked to do something that goes against one’s deeply held beliefs);

- Good team: A team where each member feels confident both in the competence and goodwill of fellow team members, and doesn’t need to wear the “corporate face” at work, but can come as oneself, discuss ideas aloud, make suggestions, take initiative and most importantly, try things and make mistakes knowing that this is okay and will be supported by the team, not blamed;

- Supportive immediate boss: People join companies and leave their bosses – having a supportive boss makes a huge difference. Supportive means being (1) fair, (2) showing you how to do stuff and (3) taking into account your opinion when you have one and taking on board the obstacles that you encounter so you can work out specific solutions together.

- Intuitive work environment: The more intuitive the environment, the more we trust it. The harder we work to make the environment intuitive, the more we get attached to it. On the other hand, if the very work environment is a daily challenge, it’s easy to get distracted from the core mission and only focus on how the workplace is supposed to work. There is nothing more dispiriting than being constantly interrupted in the process of achieving simple tasks.

- Stability and space to grow: Humans need both stability and challenge, which is part of the fun. They need stability of working conditions as well as some space for initiative and development. We are all both loss averse and prone to habituation (we get used to what we have so it’s no longer so desirable). This is precisely what keeps us creative, but also an incredibly difficult balance to manage.

Where Respect Begins

If we place it in this context, we can see that “respect for people” can mean something quite different from the casual sense of respect as being polite and not criticizing others. Respect means seeing the potential in every person and working hard at creating the conditions for this potential to realize itself, which means designing a working environment “natural” for humans to work, think and be creative, rather than one that constrains humans into behaving like soulless robots. As a manager, this can be tested on the gemba at any moment by looking at any person there and asking yourself:

- Do I have a mental image of the potential I see in this person (or do I immediately focus on what they are doing wrong that I have to correct)?

- Can I see what I can change to support this person in realizing their potential (or do I focus on how they should better adapt to the existing work environment)?

Respect for people doesn’t start with challenging others – it starts with challenging ourselves.