Dear Gemba Coach,

We use a kamishibai board along with standardized work and visual management to sustain our lean efforts on the factory floor. It works great. You’ve written about standardized work and visuals but not kamishibai cards. Don’t you use them?

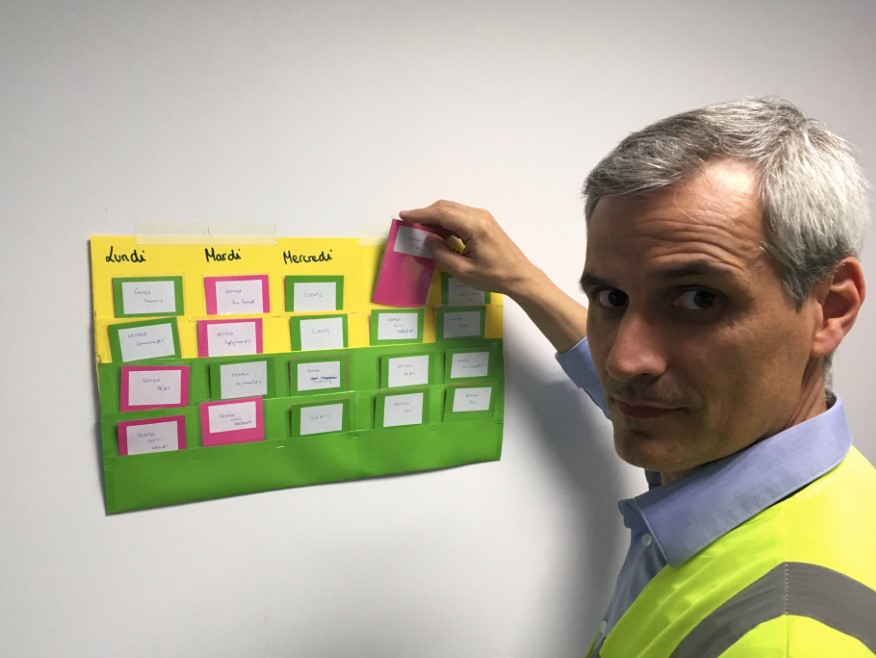

Oh absolutely. Here is Cyril Dané, the CEO of AIO using a kamishibai board for his gemba walks.

I first saw a kamishibai board in the maintenance area of a Toyota cell. It looked like kanban cards for maintenance. At regular intervals, the maintenance operator pulled a card that told him “go and …” At the time I thought nothing of it because I’d seen Toyota use cards to steer activities in many different contexts, from production to components picking in the warehouse.

The kamishibai board he uses is not about control, but about keeping a fresh mind and, regardless of the pressing concerns of the day (he has many), take a deep breath, open the chakras, and go and investigate some aspect of his business to look into conditions, not just causes.I was surprised to learn later it had a name – kamishibai – and that name came from Japanese traditional storytelling. Children are taught to create a mini-theatre and show pictures as they tell the story, like storytelling supported by a storyboard in cards.

In any case, I started paying attention to kamishibai applications when visiting plants and what I mostly found was, you guessed it, yet another form of pretending to do the work. People used the kamishibai format for auditing or checking processes, not for involving maintenance operators in their work. Some specialist department drew a list of all the tasks maintenance should do, there was a planned maintenance plan in the computer, and the cards were used to check whether the plan had been done or not – while the gemba remained as uncared for as ever, indicating that neither the plan nor the auditing was being done.

The question to ask oneself with kamishibai is the same as with all lean tools: how are we supporting voluntary participation in quality? Maintenance is specific because it’s complex to plan and quite spread out. Maintenance work essentially breaks down into:

- Responding to breakdowns

- Changing critical parts at a regular cadence

- Checking all the small things to make sure they don’t go awry

The nature of life is that small invisible forces eat at everything, whether organic or mechanic. This is entropy. Organic beings have ways to cope with it to some degree and self-heal. Mechanical beings have us. The kamishibai board responds to a very specific challenge:

|

Challenge |

Response |

|

Breakdowns |

Show up quickly, fix as fast as you can |

|

Planned maintenance |

Change the part at a fixed rhythm |

|

Random things that go wrong |

Have a routine to go and see and look whether all is okay can something be fixed immediately, or must a job be added to the to-do list |

An Aid for Better Understanding

The list of things that can go wrong in a plant is so long that it simply won’t fit in anyone’s mind. Which is why breaking it down into “go check this today” and “go check that tomorrow” is very helpful.

But it’s only helpful if you understand what you’re supposed to check and how what you see triggers action or not. The storytelling part of kamishibai is essential. The deeper thinking in the technique is about discussing with maintenance teams the story of how the plant runs, their routine journeys through the plant to make sure all is A-OK.

In other words, to develop their understanding of the plant as a system and to learn to recognize which variations can be lived with and which are a problem.

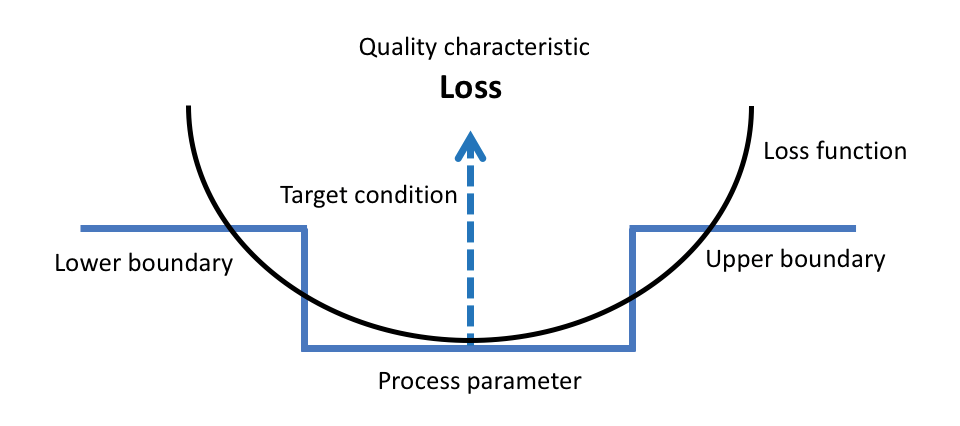

Deeper thinking here is to look at the entire plant as a complex machine and develop an understanding of the Taguchi curves of its components:

How close are we to the edge – when the machine breaks down – or how far – it can tolerate some more wear before we have a problem.

Kamishibai, as I understand it, is not about layered audits, leaders standard work, team leader routine and so on, so that maintenance becomes habitual. But, on the contrary, it’s a support for deeper observation and deeper discussion to test our assumptions about how mechanical systems work and which part is sensitive to which kind of conditions.

If you use kamishibai as a convenient way to pilot and monitor your planned maintenance with cards, you miss the essential point. We don’t want to reinforce routine. We want to create “surprise” cards so that people go and see something they have not planned to and investigate:

- Normal or abnormal?

- Do we have a problem? What would be the cause?

- Do we need an immediate countermeasure?

Which is how Cyril came to set up his own gemba walks kamishibai. As his business expanded from manufacturing karakuri (haha – from Japanese mechanical toys) to designing apps and complex software, he felt he was losing track of production as the number of important topics to “go and see” exploded.

It’s for Storytelling, not Control

The kamishibai board he uses is not about control, but about keeping a fresh mind and, regardless of the pressing concerns of the day (he has many), take a deep breath, open the chakras, and go and investigate some aspect of his business to look into conditions, not just causes.

To answer your question, I don’t write much about kamishibai because I feel it’s one of the more advanced tools with a huge potential for misinterpretation in terms of creating visual controls to routinize work, with the added advantage from command-and-control management that we can, visually, by looking at the board see if the control tool is used or not – I know too many managers who’d just love that.

On the other hand, having a kanban instruction for go-and-see is indeed very powerful and, yes, we do try to introduce it as soon as people are ready to grasp the paper play (Kami = paper, shibai = play) dimension of the tool. The cards, as a whole, should tell a story of what we understand of how the plant, as a system, works and what kind of variations should we look for.

The story of a breakdown is the same as the script of any movie: once upon a time … every day all day … until one day … because of that … because of that … because of that … until. To maintain the continuity of business we need to learn to spot the “until one day” and correct it before the chain of “because of that” becomes catastrophic. The story told by the cards is the tool to help us deepen our understanding of conditions, cause by cause.