Standard work is one of the three elements that Taiichi Ohno established as the foundation of the Toyota Production System, along with heijunka (workload leveling) and kaizen (continuous improvement). Its use in customer-facing operations is well-established, but how do we incorporate it into our lean accounting practice? Mark DeLuzio, a lean accounting pioneer and thought leader, shared insights and examples in a recent interview with Mike De Luca.

Mike: Will you please share a little bit about your background for our readers?

Mark: I started in finance and cost accounting and worked for various companies, including Lego, a typewriter company, and a company that made blasting products for the mining industry. In the 1980s, I went to work for Jake Brake (Jacobs Vehicle Systems, a Danaher subsidiary). Art Byrne and George Koenigsaecker asked me to bring the accounting function in line with the lean thinking in manufacturing.

I studied with Shingijustu in Japan and learned more about lean — that’s when I realized that the traditional cost accounting process was not only inappropriate, but it impeded successful lean transformation. I also learned that the accounting profits don’t really tell you the company’s true financial health — you have to look at other measures, including balance sheet metrics, inventory turns, etc. Among other results, we were able to free up cash flow and reduce actual unit costs.

Our traditional accounting metrics and standard cost accounting were driving dysfunctional behaviors when we finally understood lean management principles.

In 1989, I believe we were the first to bring lean thinking to accounting because it was the right thing to do. I needed to disband all the traditional cost accounting education I previously received and think entirely differently about the accounting function. Our traditional accounting metrics and standard cost accounting were driving dysfunctional behaviors when we finally understood lean management principles.

In my tenure at Jake Brake, I moved into the CFO role, then moved to an operational leadership role, and ultimately moved to Danaher to create the lean business system for the whole company, known as the Danaher Business System (DBS). In 2001, I left Danaher and started my own company, Lean Horizons Consulting, LLC. Since then, I’ve worked with companies in various industries on their lean transformations, including insurance, manufacturing, pharmaceutical, healthcare, and financial services.

You’ve commented in conferences and online discussions about the importance of standard work. In what ways do you feel it’s indispensable for us in lean accounting?

Standard Work is one of the three elements that Taiichi Ohno established as the foundation of the Toyota Production System (TPS) “House,” along with heijunka (workload leveling) and kaizen (continuous improvement) as shown in the illustration below.

The Toyota Production System “House”  Source: “Lean Lexicon: a graphical glossary for

Source: “Lean Lexicon: a graphical glossary for

lean thinkers” 5th edition, Lean Enterprise Institute, page 110

One of the requirements for standard work is that it has to be a repeatable process. So, what does this mean for the administrative side of the business — accounting processes such as payables, receivables, etc.? We must have standard work regardless of what the work is. The components of standard work are takt time, work sequence, and standard work-in-process. Standard work for a repeatable process in accounting has the same components. For other work in accounting where one or more of these components don’t apply, we still have a written standard procedure. We can distinguish between standard work for a “value object” that we’re processing, such as an invoice, and standard work that needs to move forward with a best practice that is written down and everyone follows, such as an analysis. In both cases though, we have to agree to and document the standard work as the “one best way” to perform a task or operation.

I have 10 rules for lean processes; the first one is: “If a process is not documented, it is not a process. Poor quality and customer service, variation, and high costs will be the end result.”

I have 10 rules for lean processes; the first one is: “If a process is not documented, it is not a process. Poor quality and customer service, variation, and high costs will be the end result.” If your process is not strictly repetitive, such as month-end close, report production, and cash collection, it still needs to be mapped out. Creating standard work is important because once we have documented the established process, we can improve it.

To your point, Masaaki Imai has been quoted as saying, “It is impossible to improve any process until it is standardized. If the process is shifting from here to there, then any improvement will just be one more variation that is occasionally used and mostly ignored. One must standardize, and thus stabilize the process, before continuous improvement can be made.” Can you give us an example of improvements you’ve made in accounting, starting with establishing standard work?

One example is our application of standard work to Accounts Payable. By standardizing the work, we improved it so significantly that instead of needing three people to do the work, we only needed one. That allowed us to re-deploy the other two people to other priority work.

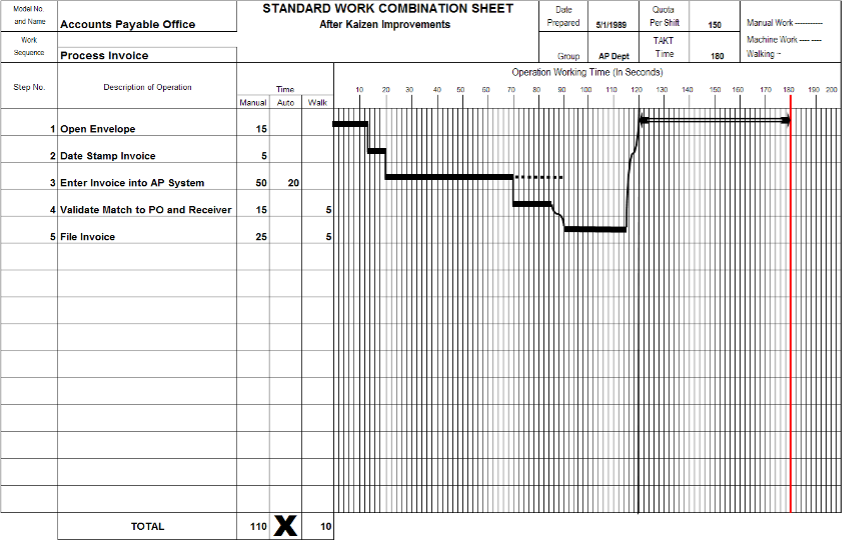

We started by putting the standard work in place as the basis for improvement, in this case, by agreeing to and documenting the one best way to pay an invoice and establishing actual takt and cycle times (rate of demand and standard process time). (See a sample standard work combination sheet below.) That allowed the team to ask themselves what was getting in their way of being able to predictably pay invoices based on the takt and cycle times. In other words, we started with “this is how it should happen when there are no deviations” – but since that’s not always the case, we asked why.

Many of the causes were around quality issues and re-work. So, we worked on moving to first-time quality (an error-free system) by addressing the Pareto of problems and defects. The number one issue was that the purchase order (PO) was missing, so the AP staff member had to track it down. We used a Pareto analysis to determine which functions and suppliers the majority of the missing POs were related to. The analysis helped us focus on engineering, where two to three suppliers were connected with 80% of the purchases without POs. The team implemented a process with a minimal administrative burden to ensure each purchase had a PO.

Standard Work Combination Sheet – Invoice Processing (excerpted from “Lean Accounting Presentation – Jake Brake Case Study” by Mark DeLuzio; used with permission.

Standard Work Combination Sheet – Invoice Processing (excerpted from “Lean Accounting Presentation – Jake Brake Case Study” by Mark DeLuzio; used with permission.

The point is that without documenting a best practice and actual takt and cycle times, we wouldn’t have had the foundation we needed to identify and analyze deviations. You document the one best way to do the work — which you know you won’t be able to meet all the time — then you have the inputs that can be prioritized to do kaizen, use PDCA, and get closer to the ideal. And you have to observe the worker do the work, time it, and understand the rate of demand for the work. This approach can be applied to any transactional or repeatable process, whether it’s paying invoices in manufacturing or documenting insurance coverage in healthcare.

How have you helped accounting and finance teams embrace the importance on lean accounting, especially in the context of some of our less transactional, repeatable work?

I once had a conversation with the leader of a hedge fund, part of which went like this:

“If I gave the same set of data and circumstances to 100 analysts, would they come up with the same investment recommendation?”

“No.”

“Then you have variation in their process. What process do they follow?”

“Well, it’s based on their experience and intuition.”

People think they’ll give up their creativity … but the opposite is true. The greater the degree of standardization, the more flexible you become, which opens the door to creativity.

This issue of standard work discounting or undermining the value of experience and intuition in knowledge work comes up frequently. The analytical work we do in finance and accounting is informed by our knowledge and experience, and creativity comes in as an argument as well. People think they’ll give up their creativity, lose their flexibility in applying their knowledge and experience, but the opposite is true. The greater the degree of standardization, the more flexible you become, which opens the door to creativity.

The reason for this is when you take out all the unnecessary variation and all the distracting noise in the work process, you increase the quality of the output. With a standard best-practice approach to the analysis, you can look at decisions that didn’t result in the intended outcome and analyze common elements that were included or excluded from the analysis. You may discover that there are common elements that should always be considered. Then you can check-adjust the process because you have a standard, best-practice framework in place that makes the best use of the knowledge and experience on the team. (Mike’s side note: I’ve worked with two teams — one a tax audit team and the other an FP&A team — and they came to the same conclusion about the value of standard work for analysis.)

To sum it all up, anyone in business can apply standard work to knowledge work, whether it’s transactional or analytical work in accounting and finance, or research and development, etc. At first, people may think you’re challenging their individual capability. It’s important to help them understand that it’s instead about creating the space for their capability and creativity to really blossom.

Key Concepts of Lean Management

Get a proper introduction to lean management.

Hi Mark. I miss you. Please let me know how I can be in touch with you.

And about the interview: You are right, without standard work, there is no real improvement and without lean accounting there is no lean perspective about next step, about lean results, about nothing.

Lean bless you

Kazem