We will come out of this, one way or the other, whether we stagger out of it, uncertain of where we are going, or emerge stronger than ever remains to be seen. But for now, we will still need to produce things and, in fact, many manufacturers continue to produce things today. Others are preparing to go back to work soon.

Can producers emerge stronger? My feeling is that some sectors will eventually be stronger than ever, finding opportunity amid crisis. Some companies will be stronger simply by virtue of emerging more adeptly than their competitors. Others will be wounded seriously, some fatally. How can each of us ensure that we emerge as strong as possible, with as much stability as possible, to face the new uncertainties that lie ahead, the as-yet-unknown new-normal that awaits us after we all finally go back to work?

I have written about how lean thinking applies to the design of production work under normal circumstances; and explored how lean thinking and practice and the Toyota Production System never strays far from looking deeply at the value-creating work to be done while in the process engaging those who do the work in a partnership to make their work more meaningful. But what about work design in this unprecedented but possibly new-normal circumstance? How can we let lean practice anchor our thinking during a time of massive disruption in the foundations of how we work together to create value?

Above all, what does lean thinking have to say about the design of work in light of the concerns, constraints, and challenges presented by the coronavirus and social distancing?

Many of you are engaged neck-deep in the scramble to establish effective working conditions in real time at the Gemba right now. While I am not writing this from a production site, I have had the opportunity to speak with folks doing this hard work, and will share a few principles and practices that we know to be true. Lean practitioners are coming up with innovative countermeasures in the course of tackling unprecedented yet common challenges.

I reached out to two companies with deep lean experience GE Appliances, a Haier Company (GEA) and Herman Miller to learn how their leaders and production teams are responding. Rich Calvaruso of GEA and Matt Long of Herman Miller report that lean thinking and practices have enabled them to respond quickly and with great agility to current frontline challenges.

Applying Lean Principles in Principle

GE Appliances and Herman Miller are both still operating right now. For GEA, home appliances are considered essential infrastructure. People need to refrigerate their food and wash their clothes, so is allowed (under national and local guidelines) to continue to operate. For Herman Miller, production for general industry has ceased but continues for critical orders from healthcare organizations and government agencies, as well as production of PPE for nearby (western Michigan) hospitals.

Leaders from the two companies generously shared the many details of how they addressed their current situations by implementing practical countermeasures to maintain production. In this article, I’ll share the lean thinking that informed the changes, with a focus on the physical work of production, not office or knowledge work though I believe the principles will apply there as well. You can learn details of how the companies identified and implemented the changes in The Impact of Social Distancing on Assembly Operations.

Problem #1: What Is the Problem to Solve?

The efforts of GE Appliances and Herman Miller reinforce several core lean principles and tap into basic lean practices that can lead to needed solutions while developing essential skills and mindsets. Let’s start with the first and perhaps the primary principle: The application of lean practice begins by considering what problem needs to be solved. The question What job needs to be done? applies to the myriad principles and practices associated with work design.

Regardless of the current state, we always wish to design jobs that are safe, effective, efficient, and friendly to the human doing the work. Today, the conditions impacting safety, effectiveness, and efficiency present tremendous challenges. Also, work comes in many varieties, so the work design must specifically address issues encountered at the Gemba. A job shop will look different from a large OEM, an emergency room, even more. Still, work process changes derive from the same, or at least similar, questions:

- How does social distancing impact the work?

- Are companies jumping to conclusions or adopting solutions to problems without breaking them down for a more in-depth understanding?

- Are they stuck in unproductive hand-wringing, unable to move forward productively?

- Are they addressing issues methodically, one at a time?

Problem #2: Arriving at Your Work Area Safely

The first order of business is to get people into the factory safely. Knowing what we know of how the virus spreads, we don’t want sick people in the factory. This virus can be carried by individuals unknowingly. What’s a basic test to know if someone is sick? So far, the standard approach is to check if they have a fever (this isn’t perfect, but it’s a logical initial hurdle). Sounds easy enough. But, as with solving most problems, even seemingly easy ones, it can take several tries. Such was the case for the GE Appliance team, which was guided by Rich and a cross-functional team that included Quality, EHS, and Operations. When the group first looked at the problem, they discovered they had two problems to solve: what type of test to use and how to scale the solution.

As a result, to design the work of checking temperatures of the thousands of employees entering the massive GE Appliance Park facility involved conducting a series of trials. With each iteration, the team tackled identifying a safe way to measure each employee’s temperature while achieving takt and cycle times that were practical. The result so far? Each employee gets their temperature taken by a thermal camera as they walk into the building with a simple pass-fail test and two lanes: pass and go to your workplace; fail and follow an exit path. The resulting cycle time was an impressive six seconds. Still two seconds off the takt time of four seconds, but getting close!

Rich Calvaruso testing the thermal imaging process at GE Appliance Park

Once the first (simple?) hurdle is passed — entering the factory safely without endangering others — we need to get to work. And a thousand more problems crop up. Not least of which is the configuration of the work itself.

Work Design — Standardized Work in Normal Conditions

Configuring, improving, and addressing the problems raised by standardized work are among the most fundamental of lean practices. Standardized work means recognizing the required output, defining the steps and their sequence, and determining the amount of WIP (the amount of stuff that needs to be available and maintained to complete the process). It also requires setting the Takt Time (the customer demand rate) and the Cycle Time (the amount of time required to do the work as currently designed). Sometimes the customer demand rate is quite steady over a specified time; other times, not so much. The cycle time is sometimes consistent, repeatable, and stable; other times, not so much. Wrestling these variables to the ground is a focal point of standardized work in normal times, and this principle is more critical during a crisis.

To establish and steadily improve standardized work, we have three primary tools: Standardized Work Chart, Standardized Work Combination Table, Process Capacity Sheet, which are sometimes combined with others, such as the operator balance chart, known by many now as the yamazumi Board. Importantly (always, but especially today given the challenge at hand), we define standardized work not for just one person, but every worker. We must be cognizant of how the work of different workers intersects, maintaining vigilance as we design the work and seeing how the work of worker A impacts worker B, how they may help each other at times, and stay out of each otherís way at others.

Problem #3: Creating Standard Work that Meets the Conditions of Social Distancing

Take an assembly line with a takt time of 30 seconds and a work station pitch of 3 feet. Three feet constitutes close quarters — entirely too close for today. What to do? Can you slow the line down to half speed (60 seconds) and increase the pitch to 6 feet? Or, slow it to 120 seconds and 12 feet? Of course, that reduces line output accordingly (unless you have the space to extend the line, which would take time to implement).

If reducing the line rate and increasing the spacing between pitches is not possible, can safety shields between each worker be employed? They would need to be procured or fabricated, of course, but perhaps something simple can suffice. They don’t have to be pretty just a barrier between workers. It would be great if they can be transparent (think of curtains that protect workers from sparks flying from welding equipment).

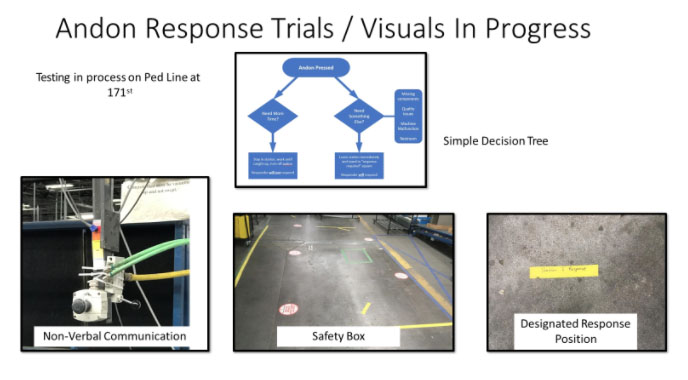

And what to do about Team Leaders responding to Andon calls? Ordinarily, Team Leaders go directly to the worker’s side to help. What care must be taken in these conditions of social distancing? Can you create rules of engagement, with carefully and visibly cordoned safety boxes?

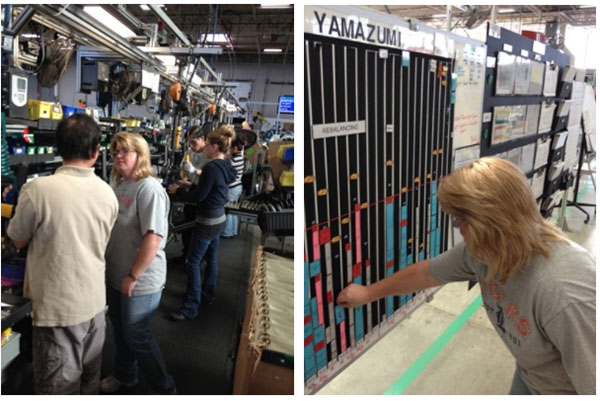

At job sites that are operating, Herman Miller has responded by redesigning all jobs and developing new rules of engagement for Team Leaders. The company has used standardized work charts and yamazumi boards to rebalance its assembly work.

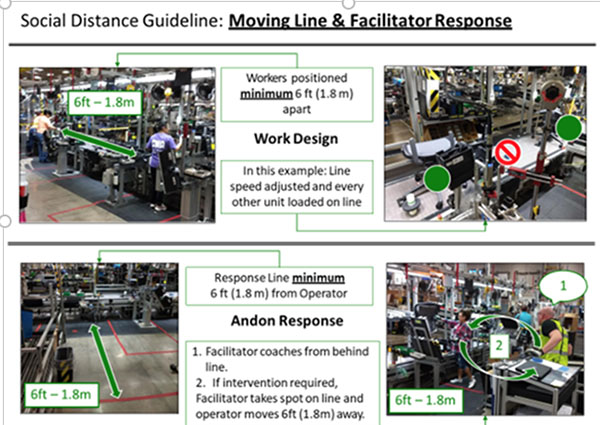

Example of Herman Miller guidelines for work design and team leader Andon response with social distancing

Problem #4: Creating Standard Work to Keep Team Leaders Safe

Team Leaders have long been trained to step in quickly to help any struggling Team Members with problems — this is a preexisting and almost genetically coded habit at both Herman Miller and GEA. Team Leaders now maintain a six-foot distance when responding to any calls; this standard is reinforced by markings that clearly indicate the safety zone, as Team Leaders practice to develop new habits.

With the new standard, when Team Members call, the Team Leader will respond as usual but will stand at six feet distance. If the operator’s problem is one of timing or something the TM can take care of by him or herself, the T/L allows the TM to take the time needed to sort it out and then inform the T/L of the issue, so it can be documented. If the problem is something that requires T/L to step in, the TM steps aside, the T/L steps in and intervenes, then steps away, and the TM returns to the station. New choreography.

Another challenge Herman Miller addressed is how to handle new team-member training. In this case, the T/L, already wearing a mask, adds a face shield to protect the TM while administering JI training in close proximity. The company is also testing technology to help the TM be able to see step-by step-instructions while trying it themselves.

Safety Box: A designated response position for responder. Entails and requires non-verbal communication.

A New-Normal for Lean Operational Practices ñ At Least for Now

Traditionally, we have used the lean work design tools to move things closer together. The LEI workbook Creating Continuous Flow, for example, describes the conversion of traditional process village layouts into u-shaped cells. Moving equipment closer together, reducing the distance, time, and amount of WIP between each machine, combined with carefully orchestrated handoffs between workers, enabled a suite of advantages. Among them: shorter lead time, reduced inventory, less space, improved visibility of quality performance, easier problem solving, more engagement of team members, and better teamwork.

At least temporarily, the direction of improvement will, in some ways, be the exact reverse — things will be moved apart. Fabrication cells may become larger. Assembly lines longer.

Further, takt times will likely fluctuate, probably be even more unpredictable than ever.

So the winds facing manufacturers have taken a drastic turn. As Kiyo Suzaki says, “We can’t change the wind, but we can trim our sails.” In this environment, those who are most skillful at trimming their sails will win the race. The lean capabilities developed by lean producers like GE Appliances and Herman Miller won’t prevent loss of customer orders or a sudden tsunami of orders (such as some toilet paper manufacturers may have faced). Still, they will enable companies to adjust as rapidly, with as much agility, as possible.

These two images from my eLetter of December 2012 show Herman Miller assembly line leader Dawn Lowrie in one instance supporting an assembly line worker and working the yamazumi board in the other. One of the scenes, team leaders examining work reconfigurations, should become an ever more common sight. The other, team leaders working shoulder-to-shoulder with team members ñ we may not see for a while

How New Practices Created in Crisis Will Lead to Lasting Improvements

Will Team Leaders learn to make a habit of stopping to check before rushing in, relying more on coaching and letting Team Members solve more of their own problems? Might this pay rewards in fostering a greater sense of problem ownership and skill development on the part of the workers?

Will we eliminate overburden instead of spread it around? Job rotation to distribute the burden of a difficult job is common today in many companies. Herman Miller has found that the need to clean surfaces and equipment has required them to reduce the frequency of job rotation. They have discovered that the reason for the frequent job rotation on some jobs was the burden of doing that job. Since they can no longer rotate so frequently, they have been forced to look at the actual work itself, asking what can be done to eliminate the burden, rather than merely share it more frequently. This led to the recognition that, in some instances, frequent job rotation was being used as a workaround for poor job design! With this insight, they are examining the jobs anew with classic lean thinking: see the problem for what it is (go see), identify the cause of the problem (ask why) and eliminate it at its source, relieving the unnecessary burden on the workers (show respect).

Cleanliness. Awareness of the benefits of a clean worksite has never been higher. It seems reasonable to expect these new habits to pay dividends next flu season, helping prevent the spread of ordinary flu and colds.

Don’t come to work sick. Mom’s advice was right — when you’re sick, stay in bed. Yet, many of us push through, we go to work even when sick, perhaps to show the boss and peers that we are dedicated and tough. Or, sadly, we don’t want to use up limited sick days (“I don’t want to waste a sick day staying home sick.”). And this is compounded by the poor sick leave policies (and healthcare benefits in general) of many companies (not GEA and Herman Miller!).

As operations engineers and workers make improvements for social distancing in cell production and job shop environments, what practices can be brought into office work? While I have long been a proponent of the open office, how might the new-normal impact the trend to more open office environments? Will this trigger a revival of high-partition cubicles? Or even, egads, private offices?

GE Appliances and Herman Miller have adjusted many existing standards. They are looking at others, especially those at the Gemba, such as halting the use of all personal fans that blow horizontally, limiting the “incidental closeness” that occurs at water fountains and in the restrooms, and even the process of safely providing new PPE like masks, face shields to all workers. For more examples of and details about the countermeasures theyíve applied to several other problems they have faced, read The Impact of Social Distancing on Assembly Operations.

The question of when auto factories can resume work is a hot topic here in Michigan. State Governor Gretchen Whitmer is expected to issue guidelines soon, which will precipitate auto assembly lines getting back to work. The UAW is hesitant. Whether you produce cars or car parts or appliances or furniture, you can go through the same process as GE Appliances and Herman Miller to redesign your assembly lines ñ and other work as well. The deeper your experience with the lean tools associated with standardized work, the more ably you will be able to make the shifts necessary and get back to work SWIFTLY and SAFELY.

The Perfect Rallying Cry

I think the phrase “Emerging Stronger” is the perfect rallying call for all of us now. I borrow it from a lean champion at yet another company, Bernardo Sole, at the oil and gas supplier TechnipFMC, who coined it as an operating theme to cope with the virus crisis. Facing the same challenges as GE Appliances and Herman Miller, in addition to adjusting to a collapsed market due to the oil price drop, TechnipFMC has been grappling with sheltering in place, customer order uncertainty, financial market jitters and, wherever onsite work is continuing, social distancing. After the same initial flailing about that most of us went through, TFMC is settling into new routines, new ways of collaborating when staff can no longer meet face to face, with the determination to emerge stronger. Going back to the old ways isnít an option for them. Companies are challenging the way everything is done, recognizing that they must emerge stronger or face the possibility of not emerging at all.

For all of us, the crisis is happening, whether we like it or not. What choices can you make, what actions can you take, to ensure that you — and we all — emerge stronger.