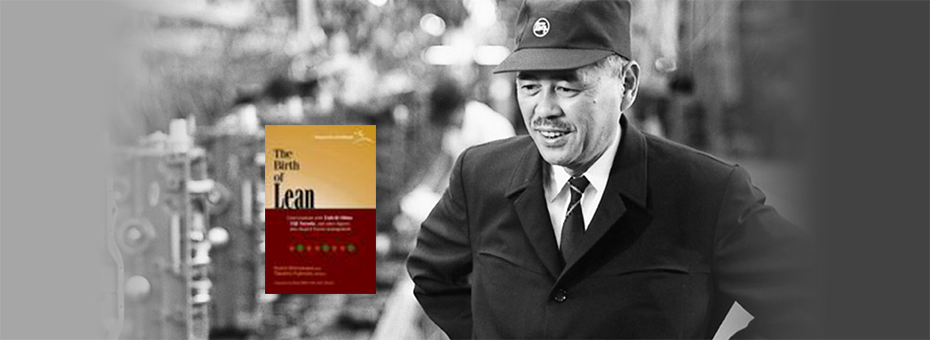

Are you struggling with the challenge of introducing lean to a team? If so, you will find guidance and inspiration in The Birth of Lean, a 2009 book published by LEI that is comprised of interviews with Taiichi Ohno, Eiji Toyoda, and other creators of the Toyota Production System. This stellar resource can help individuals shape their future, by sharing the history of the thinking of TPS, which many refer to as the thinking production system.

Many of LEI’s best-known thinkers have identified the power of this collection in deepening their understanding of the essence of lean. Jim Womack, John Shook, Jean Cunningham, and Michael Ballé have all identified notable elements of lean practice that are uncovered in this book.

One huge takeway is that TPS was never conceived as a new and comprehensive system designed to replace conventional enterprise. Rather, the system evolved over years, and then decades, as the founders persistently tackled emerging problems and then folded their learning into practice. The term continuous improvement refers as much to this open mindset as it does any list of specific new techniques and practices.

“The ability to nurture a capacity for perseverant organizational learning amid chaos is arguably Toyota’s most essential core competence,” note Koichi Shimokawa and Takahiro Fujimoto in the book’s preface.

LEI founder Jim Womack identifies this emergent quality in his foreword:

“At a time when all of us are struggling to implement lean production and lean management, often with complex programs on an organization-wide basis, it is helpful to learn that the creators of lean had no grand plan and no company-wide program to install it. Instead, they were an army of line-manager experimenters trying to solve pressing business problems, in particular a lack of financial resources, to grow rapidly without accumulating large inventories.”

As Michael Ballé argues in his review, the organic process that led to the creation of “Toyota’s revolutionary approach to knowledge creation” came about through careful and deliberate trial and error over time. He elaborates:

“This is no longer thinking on one side and executing on the other, but a continuous process of challenging, experimenting, and learning. Vision here is not a destination, but a few key high-order problems we need to resolve to get ahead on our markets. Execution is not about applying what has been developed elsewhere, but relentlessly using the analysis method which has given good results elsewhere, in the spirit of kaizen—small, rapid improvement cycles.”

Ballé also identifies the way that the spirit of discovery can be nurtured but never controlled. Lean is not a disembodied school of abstract thought taught in a classroom by distant teachers; nor can lean practice be planned and directed from those without an active presence at the work itself. Lean was discovered through constant experimentation by a unified team of eager improvers who proposed and tested ideas, and then rolled up the improvements that proved successful into a better way.

“I do not believe lean culture can be implemented by having a ‘lean’ body of knowledge on one hand and a traditional implementation approach on the other. Lean culture is the result of acquiring lean values and lean practices. Yet many lean programs tend to be built around a traditional vision of implementation. One usually finds some sort of roadmap (tools to be implemented, by phase according to a set sequence), implementation by staff specialists who conduct training sessions and workshops, and control by an auditing structure of how ‘lean’ the sites are—not according to their operational results but to their implementation of the roadmap. By contrast. The Birth of Lean shows how senior managers have acquired a deep understanding of the principles and relentlessly challenge their operational line to solve the corresponding problems rigorously. This is a radically different sort of lean program, where the priority is getting a sensei to work with senior executives and define short-term and mid-term challenges to be resolved in a ‘lean way’ (no investment, and applying the tools properly.) Certainly, this requires some initial training to the tools at the shop floor level, but the emphasis is on maintaining the kaizen pressure to resolve the problems one by one.”

This work involved a constant balance of the technical and the social—learning how such practices as standard work and Kanban could create an environment for kaizen. As Jean Cunningham notes in her Thoughts on the Birth of Lean, “Standardized work is a framework for kaizen improvements. People are not doing their job if they leave standardized work unchanged for a month.”

Finally, for those who want to dive into the many gems to be found, you can start with John Shook’s Thinking About Buffers and Production Systems, which shares and contextualizes many quotes from chapter four. Or you can read his Michikazu Tanaka of Daihatsu on What I Learned from Taiichi Ohno which highlights excerpts that John considers close to his heart.

(You can download the foreword, preface, and introduction to the book here. And you can download chapter two of the book here. Finally, the complete book is available for purchase in the LEI bookstore.

And if you are interested in learning more about this topic, join the free session about Lean Thinking’s Past, Present and Future, led by Jim Womack in the upcoming Virtual Lean Learning Experience.)