Have you ever walked another organization’s gemba and spied one or more visual controls that you thought worthy of emulation? I know that I have.

Your interest may have been piqued because it was the embodiment of some of the tried-and-true characteristics of an effective visual, such as: self-explaining, worker managed, and effectively prompting “self” correction of the highlighted abnormality.

But, perhaps the magical visual had some other, more superficial attributes – it was colorful, and pretty, and it just looked so…so…lean. So lean that it made you think, I want to be the first guy on our gemba with a cherry red Lamborghini! (The Lamborghini is a metaphor.)

And then, you surreptitiously take a picture of that visual(s) with your smartphone.

And you go back to your own company.

And you show your team the picture…with almost the same joy and amazement as when you showed them the picture of your newborn son years ago.

And then you say to them, “We need to make a visual just like this and put it over there.”

And then they act impressed and copy that visual and put it exactly “over there.”

And it doesn’t “work.” Nobody uses it. It’s like the visual is invisible to them.

So you chastise your folks for not using it, but eventually you give up. And now the Lamborghini is dusty and it’s missing most of its magnets and…it’s just a sad reminder of yet another failed, ignored visual control.

Does any of this sound familiar? Where did we go wrong?

Well, we probably violated a major tenet of lean. We did not start from need. We started by copying someone else’s stuff.

Indeed, as John Shook has said, lean is situational. We must apply lean principles, but we also must apply them within the context of the problem(s) we are trying to solve within our own company. Our own value stream. Copying rarely fits any situational need.

Now as we introduced in a previous Lean Post, visuals can be placed into two broad categories based on purpose: visual process adherence (VPA) and visual process performance (VPP). Here, I want to focus on VPA.

As the name implies, VPA is about adherence to process standards. However, when incorporated with gemba-based leader standardized work, it also has to do with the sufficiency of the process. VPA tools include things like operator standardized work; material replenishment systems; and their cards, totes, boards, etc.; and production analysis boards. These tools help the workers and lean leaders quickly identify abnormalities, ask why they are occurring, and make the necessary adjustments.

So, how do we start with need when designing VPA?

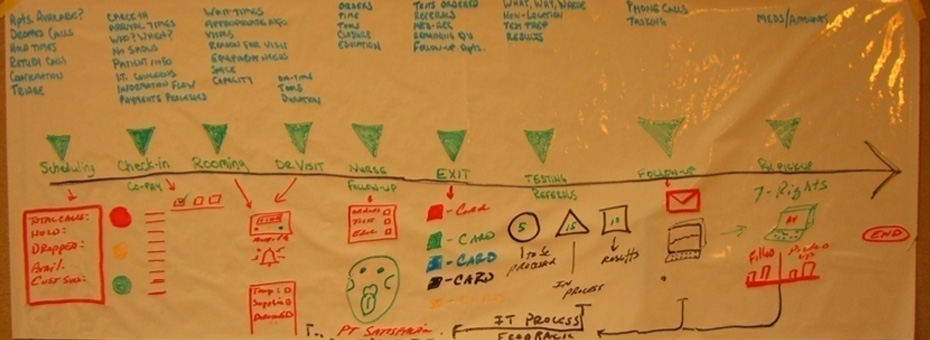

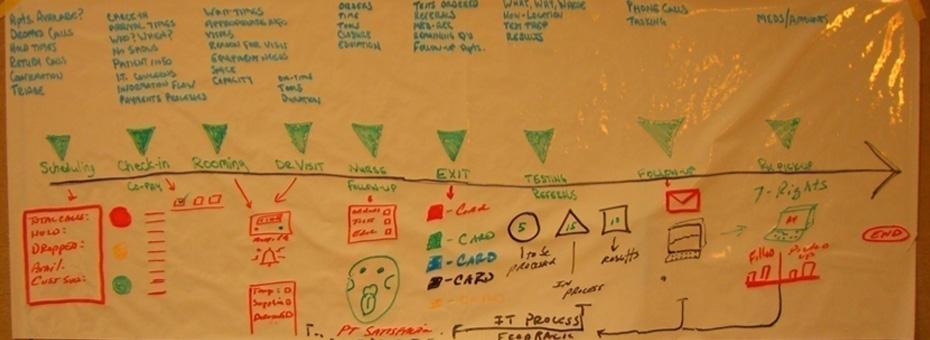

I always recommend a tool that is the brainchild of my business partner and fellow LEI faculty member, Joe Murli. We call it the pulse point arrow (PPA) – see the picture below for an example.

The PPA is ostensibly simple, yet requires, as many good tools do, some deep thinking on the part of the practitioners! The notion here is that when anticipating the gemba walk, there are physical places along the value stream (perhaps virtual in a knowledge flow environment) where we would like to stop and take the pulse of the operation. Taking a pulse, think healthcare, is indicative of an important, but relatively quick and cursory check. If need be, we can take a much deeper dive from the perspective of more stringent direct observation and, if need be, inquiry and beyond. This might be the equivalent of an MRI or biopsy.

Now that we have identified the pulse points, as captured on the PPA’s horizontal arrow down the middle of the paper, we now move on to the need. This is what the upper half of the PPA is used for.

What are the questions relative to the process control that we want to answer (visually)? What do we need to know? For example, at the Check-In pulse point within an ambulatory healthcare value stream (sorry, we’re really stretching this medical pulse-point metaphor), I may want to know if we are checking in our patients in accordance with standard work (right steps, right sequence, right cycle time, right standard WIP). Within the Rooming pulse point, I may want to know if the patient has been alone (meaning waiting for the doctor or mid-level) longer than the standard period. The questions, and often there are many, must emanate from needs based upon the system intent and design and its control.

Finally, we get to the bottom half of the PPA where we design the visual controls that give us the information needed to effectively answer the questions above. There are three status categories of visuals:

- They already exist and are sufficient (meaning they answer the question quickly and effectively)

- They exist but need to be improved

- They don’t exist…yet

Ultimately, these visuals must be incorporated within the gemba-walk leader standard work and undergo some PDCA cycles before they go “live.”

So, here are two questions for you: 1) how many once-sexy Lamborghinis are cluttering your visual ecosystem? and 2) are you ready to replace them with, perhaps less exciting, but truly effective visual controls that start from need?