“Everything you see has its roots in the unseen world.” – Rumi

Grasping certain qualities vital to understanding why something works requires going back to its roots. What is unseen, or at least seen less well today are the roots supporting lean management’s heritage.

When we think about the foundation of the Toyota Production System (TPS), the prototype lean system, often the focus is on the process improvements made possible by practices that are visible, such as just-in-time deliveries, waste reduction, and standard work.

While necessary, these seen practices are lacking, and holistically incomplete.

Lean practitioners identify, invent and test improvements through problem-solving conversations. A conversation we had in the fall of 2016 looked at whether lean is constrained by a deliberate analytical and rational way of thinking, and whether we are blinded to some new possibilities for understanding lean by focusing on it as a purely scientific discipline.

We discovered there are non-scientific perspectives worth considering, and that these new perspectives could contain clues leading to a wider and longer embracing of lean practices.

Over the course of three days, we met with a group of artists to learn through experiences, conversations, and reflection their perspectives on lean thinking and practices. Helping us in this effort were John Shook, Deb McGee, Karyn Ross, David Verble, Niklas Modig, Robert Martichenko, and Bryan Wahl. We anticipated that as most of the work investigating lean has been through scientific thinking that an artistic perspective would yield important insights that have been invisible, or at least not very deeply explored, to students of lean. This choice complemented an observation from Tom’s work in the building industry, wherein architects as design professionals tend to be most resistant to lean practices.

Three valuable insights were gleaned from the artists’ perspectives. We believe the interest, acceptance, and longevity of lean practices will improve through consideration of these insights. The first, Lean is a creative ethic, is discussed in a previous post.The second, lean has its roots in spirituality, is perhaps one of the most foundational insights of the three. Lean is a practice in search of a language, our third insight, will be discussed in a coming post.

We consider our second insight foundational in that it is not only where lean began, but where we must go in the future when sharing lean practices.

Lean has its roots in spirituality.

Ford and Confucius

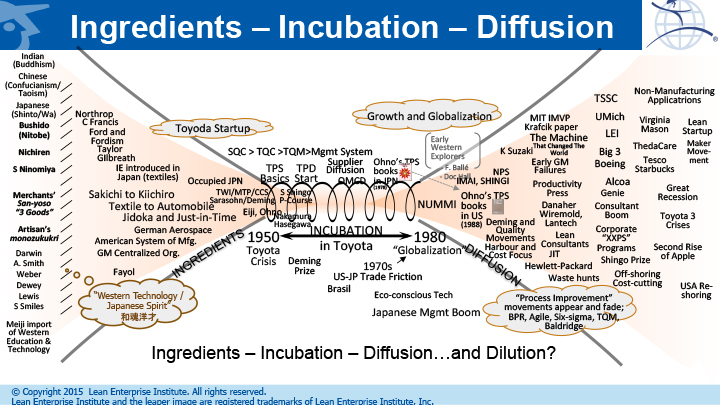

The actual statement made by one of the artists was, “Lean has its roots in arts and spirituality.” The statement resonated with the other artists. It was voiced during John Shook’s description of a diagram he created to illustrate a 30-year incubation period for the Toyota Production System. There are several dozen influences, including several religious traditions, as well as pioneers in industry and science.

30-year incubation period for the Toyota Production System.

While all these influences are known, we tend to reflect more on the influence of Henry Ford and Frederick Taylor than Confucius and Samuel Smiles. The work of Ford and Taylor fits more neatly with process-centric thinking. In doing so, we have likely missed an opportunity to highlight those influences that are best able to seize the interest and imagination of the working world, through an emotional connection. As humans, we want to know our work, take ownership of our work, and contribute to something bigger, something for the overall good. To know why something works or does not, we have to look at its root. TPS works because it has stayed true to its founding identity, which we like to refer to as core identity.

Near the beginning of Toyota Motor Company, Kiichiro Toyoda documented a summary of the teachings of his father Sakichi in a document known as the Five Precepts.

- Always be faithful to your duties, thereby contributing to the Country and to the overall good.

- Always be studious and creative, striving to stay ahead of the times.

- Always be practical and avoid frivolousness.

- Always strive to build a homelike atmosphere at work that is warm and friendly.

- Always have respect for God and remember to be grateful at all times.

All five refer to qualities of the human spirit, as opposed to material things. Together they express a great purpose, the embrace through work of ideal qualities that would lift up the peoples of a nation. These are emotional and powerful ideas that fueled not only the development of TPS, but also its endurance.

Consider this report from the Toyota Motor Corporation website:

Sakichi always maintained a sense of gratitude, not only towards members of his family or those who helped him, but also towards society as a whole. He believed he owed his success to the world at large and that it was important that Toyota be of service to humankind by working in good faith, not purely for monetary gain.

Sakichi Toyoda’s sense of gratitude was arguably a very strong emotional connection to the purpose of his work – a connection that was passed on through his son and the people that staffed Toyota in its formative years.

This mindful awareness of purpose defined by his core identity, a core identity that while teachable must be experienced. It’s this awareness that can be said to be “in the air” at Toyota. An awareness that we argue needs to be practiced daily throughout lean enterprises if they are to attain the same kind of productive and enriching working celebrated at Toyota. There is a need for a shift or refocus back to core identity aligned with purpose, avoiding repeating routines without thinking.