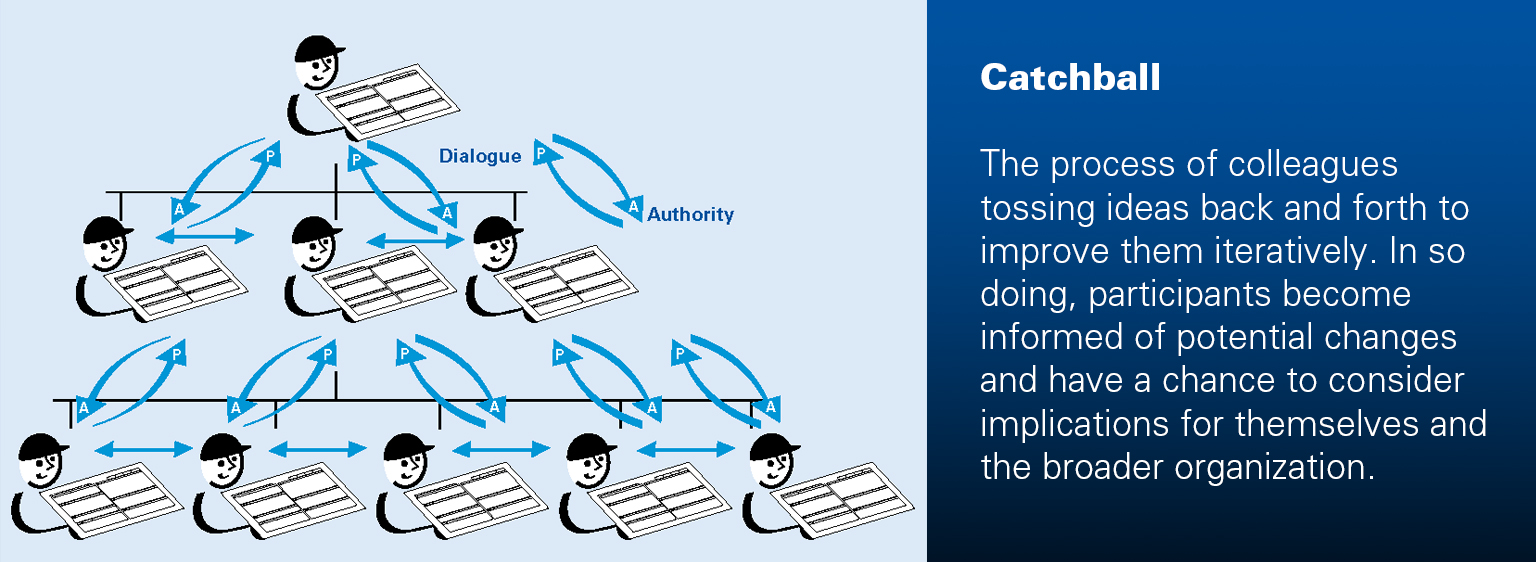

Catchball is a well-known process in lean management commonly associated with hoshin kanri, i.e., strategy planning and execution. It refers to the process of colleagues tossing ideas back and forth to improve them iteratively. In so doing, participants become informed of potential changes and have a chance to consider implications for themselves and the broader organization.

Usually, a few outcomes of catchball, such as better strategic ideas and plans and more engaged and aligned personnel, tend to be emphasized. I say this based on LEI’s research in the field and a review of articles and books that cover the topic. But there’s another potential outcome of the catchball process, one that’s oft-neglected: innovative leaders grounded in problem-solving with ownership of the organization’s strategic objectives.

Maximizing the Value-Add

I played baseball growing up, spending endless hours playing catch. It was a way to pass the time or a warm-up for activities to follow. As such, I played catch lackadaisically. Until I played catch with Coach Mike. He added intensity and intention, turning a pastime into something more.

Coach Mike, a former professional pitcher, could throw a baseball harder than anyone I’d ever met. After a warm-up toss or two, he’d start throwing the ball as hard and as quickly as he could, challenging me to do the same. “What a showoff,” I’d grumble to myself. But now, sitting comfortably at my computer 😊, I can appreciate the dual-purpose of his approach: to get the job done (warm-up my arm) and develop my capability (build my arm strength, quicken my ball transfer from glove to throwing hand)… at the same time.

Herein lies the opportunity — the challenging promise — of every lean management practice. Lean managers, wanting to maximize their impact with limited time, keep asking, “Am I getting the job done and developing capability simultaneously?”

One Way to Catchball (in a Batch)

Recently, I observed a catchball session organized by a senior executive. His company is learning to use hoshin kanri for needed breakthrough results on a few strategic objectives. He invited twenty or so managers from various functions to meet for half a day. With help from one of his deputies, the executive had drafted a strategic objective with activities and targets. To start the session, he shared this pre-work with the cross-functional group of managers and asked what they would modify, add, and delete. Discussion ensued. Edits were made.

Am I getting the job done and developing capability simultaneously?

It was all good: key stakeholders identified by the executive were engaged and made aware of the company’s strategic direction. The group’s feedback improved the plan. Plus, through discussion, the participants began to understand better what was going to happen which, contributed to organizational alignment. Unrelated to the process of catchball, per se, I’d also say that the working session built teamwork. Again, good stuff.

However, after the meeting, remembering playing catch with Coach Mike and the lean management challenge, I reflected on the activity in terms of people development and realized that an opportunity had been missed.

Another Way to Catchball (One-by-One)

Greatly informing my reflections on people development is John Shook’s book Managing to Learn. Although explicitly a book about the A3 management process, not hoshin kanri per se, its fictional story about Sanderson (manager, mentor) and Porter (team member, mentee) shows us how catchball can be used for capability development. In the book, we see vertical catchball taking place between Sanderson and Porter, wherein Porter’s development is facilitated, and horizontal catchball between Porter and his colleagues.

Here’s how the vertical catchball works:

Sanderson sets the direction for Porter by assigning him ownership of a vaguely defined problem to solve. He even suggests a tool for Porter to use: an A3, or an 11” by 17” sheet of paper structured with facts and analysis about the problem on the left side and ideas for solving the problem on the right side. Then, Sanderson sends Porter away to work on the A3, challenging him to do his own thinking about what to do.

(Note: Sanderson does not share a draft problem-solving plan for Porter to simply review and give feedback on. Remember, Porter was given ownership. Plus, for Sanderson to develop Porter as an innovative leader grounded in problem-solving, Sanderson needs to see how Porter approaches the assignment. In other words, Sanderson needs to grasp the current state of Porter’s capability. And finally, since Porter was just given the assignment, Sanderson does not expect Porter to do his thinking about the problem on the spot. More on these points later.)

Porter mulls things over and talks it through with a colleague. Then, once he’s filled out the A3 “completely,” he returns to share it with Sanderson (key point!), expecting approval of the solution he’d like to implement. Not so fast.

Sanderson, a more experienced and capable problem solver, detects several gaps in Porter’s problem-solving process. For example, Porter has not clarified the problem. Furthermore, Porter’s grasp of the current state of the problem, namely the process that generates it, is virtually non-existent. He hasn’t gone to the gemba. He hasn’t identified and talked with folks who work in the process. In short, he had committed the common problem-solving mistake of jumping to a conclusion.

(Another note: Sanderson does not critique Porter’s proposed solution. In deed, he doesn’t even acknowledge it. Sanderson is focused on the problem-solving process and not the result. As such, he knows the solution is baseless and unlikely to be very good. But, he refrains from telling Porter that his proposed solution is not good. And he refrains from telling Porter exactly what to do. Doing so would take away Porter’s ownership. More later.)

Sanderson provides coaching through a series of thought-provoking questions centered on the problem-solving process. This guidance helps Porter realize he needs to do more work on the A3. Specifically, he needs to go to the gemba where he can start learning about the process from the folks who do the actual work.

Over time, less coaching is needed as Porter’s capabilities as a problem solver, collaborator, and leader grow.

This cycle keeps repeating: Sanderson sets direction, Porter updates his A3 and proposes next steps, and Sanderson, having observed Porter’s horizontal catchball with colleagues and seeing his thinking laid out on the A3, provides further coaching and/or authorization to proceed as proposed. Over time, less coaching is needed as Porter’s capabilities as a problem solver, collaborator, and leader grow. And critically, Porter’s ownership of the problem remains intact.

Moreover, the two protagonists are “learning to learn” with a process (A3) that can be improved.

A Proposal to Get More Out of Catchball

Returning to the activity that I recently observed. While organizational engagement and alignment to the executive’s improved plan was achieved, little — if any — development took place. Therefore, here is my proposal:

- Refrain from coming up with the plan. Or better, draft a plan to flesh out your thinking but keep it to yourself. Key leaders of the team should own it.

- In terms of process, initially, go no further than setting direction. Remember, for development to occur, you need to see how the challenge is approached from scratch.

- For those key leaders, at least, set an expectation and give some time for them to do their own thinking: to learn about the “problem to solve” and its key process(es), to talk to the people who touch the problem/process, and to come up with potential next steps to propose.

- When reviewing their work, perhaps by reading an A3 they’ve put together, focus your coaching on the problem-solving process, not its output.

As illustrated in Managing to Learn, this approach develops innovative leaders grounded in problem-solving, greatly increasing the value-add of the catchball process. If followed, the executive would get the job done and build team members’ capability simultaneously, better realizing the promise of this particular lean management practice.

Moreover, the executive would nudge the organization toward taking more initiative. Who knows? Perhaps innovative leadership will emerge on its own next time — which, by the way, is Sanderson’s ultimate objective with Porter’s development. Sanderson, a very busy executive, wants an organization where ownership of problems is taken (vs. assigned) and handled effectively.