Editor’s Note: This article, updated in March 2022, is the second of 3 focused on exploring the crucial role standardized work plays in a lean enterprise. Read the first and third articles in the series.

In the previous column, we looked at the first three of the Five Missing Pieces in Your Standardized Work. Now, let’s pick up where we left off, with Neglected Piece No. 4, practice, and Neglected Piece No. 5, the role of the leader/manager.

4. Practice, Practice, Practice

For some reason, most of the time, most of us come to see our day-to-day work as mundane. I guess it’s because we do it every day.

But is that necessary? Craftsmen do their work every day. Artists paint or sculpt every day. Athletes run or swim every day. Musicians play every day. But we choose to put our daily work in a different, lesser category. The focus that lean thinking puts on frontline work changes our attitude toward work. It elevates it to a higher level of visibility and importance. For example, in my recent column about Starbucks, I suggested, “…think of the best bartender or waiter/waitress you’ve ever seen. Remember marveling at how he or she could handle orders coming from all directions without missing a beat.”

The focus that lean thinking puts on frontline work changes our attitude toward work. It elevates it to a higher level of visibility and importance.

Mastery of any skill requires diligent practice. When I was there, Toyota typically followed a sequence whereby workers would first master one job, then move to the preceding and following jobs, eventually mastering each job of the team. When I was at the Takaoka Plant, the process of learning each of the five or so jobs in a team took several years.

In the book Outliers, author Malcolm Gladwell offers evidence to support the argument that mastery of any skill requires about 10,000 hours of practice. Musicians, athletes, artisans, artists, professionals of any discipline can all be observed as requiring this 10,000-hours hurdle. Gladwell provides several examples that reminded me of some of my own favorites:

- Tiger Woods, working with a coach to rebuild his swing from the ground up following his first Master’s win, possibly the greatest victory ever in golf.

- Michael Jordan may have been about the most talented player of all time. Still, every observer and Michael himself emphasizes that the real distinguishing factor was that he practiced harder than anyone else and was the most prepared.

- Sonny Rollins, after (that would be AFTER) achieving stardom as one of the very top saxophone players in the jazz world, took three years off from performing to take his playing to a new level. Practicing alone every day on the Williamsburg Bridge in New York City, he blended his notes with the passing traffic, so no one heard his new sound until he felt it was ready. His song and album “The Bridge” were instant classics.

There is a saying in Japanese, “Three years on a rock,” meaning that it takes about three years to deeply learn any subject of substance.

- When I was at Toyota, there was a saying that one could understand the basic concepts of TPS in three hours, learn to “explain” the basic concepts of TPS in three days, and be proficient in “actualizing the concepts” of TPS in three years.

- In Toyota’s engineering and R&D world (entirely independent from the rest of the company, with even its own separate Human Resource Development Department!), it was commonly stated that “it takes 10 years to make an engineer.”

- For quick reference, Gladwell’s 10,000 hours would ordinarily translate into about four years of essentially full-time effort, or longer if pursued at a more leisurely pace.

Of course, while the specific numbers that Toyota (or Malcolm Gladwell) puts on these things is interesting, it’s not exactly the point. The point is: what do you think? What fundamental thinking regarding skill development informs your organization’s approach, system, and methods of developing your people?

(Toyota’s training, especially for employees who work on or around the front lines, is heavily informed by the Training Within Industry (TWI) program they learned from the United States following the Second World War. I’ll offer a little more information about TWI in the next section, but if you don’t know about TWI, learn it!)

5. Don’t Forget the Critical Role of the Leader/Manager

When I encounter managers struggling with getting standardized work firmly established, their questions and concerns always center around the worker, around how to get the worker to follow the standardized work. Usually, however, bigger problems are always found well before getting to the worker, often beginning with the role of the leader, especially the immediate frontline supervisor.

Frontline supervisors won’t change their behavior from compliance officer to support for success unless (1) the new expectations are made clear, (2) the requisite training is provided, and — last but not least — (3) time allocation is provided. What that adds up to, of course, is standardized work for the supervisor.

My first encounter with standardized work was in January 1984 at Toyota’s Takaoka Plant. I was fortunate to be provided the experience of six learning-packed weeks working production jobs in each of the major auto processes: stamping, body welding, paint, final assembly (followed by time in the production control office learning kanban calculations, observing training, and learning other similar support operations). All my leader/mentors were outstanding, patiently (mostly patiently) teaching me each job. It was in final assembly that I had my most intense experience with standardized work and the role of the team leader.

I was too tall for the job I was assigned on Toyota’s Corolla assembly line. I’m six feet tall, and Toyota’s guidelines in Japan would ordinarily have placed me in other jobs rather than getting in and out of a Corolla 500 times a day. But, they made an exception in my case since I was to perform that particular job for only one week, and the job was among those that were being readied for trainees from NUMMI who would begin arriving a few months later.

In addition to being relatively tall, my legs are long for my height. So, I found it hard to do the job exactly as instructed, which was to enter and exit the vehicle in the highly specified proven, safe, and effective manner — butt first. So, I quickly found my workaround, which was to enter right-leg-first. Entering right-leg-first was no problem in and of itself, but it meant that my legs would get stuck in an awkward position. Nevertheless, it seemed OK to me and was “easier” or preferable to me than doing it the prescribed way. (This all falls under the heading of “knack.” When Toyota teaches standardized work, in addition to stipulating the sequence of work elements (as noted previously under the three elements of standard work), they teach each work element using the TWI Job Instruction methodology. However, many elements of the job require a certain “knack” to accomplish satisfactorily. People generally assume “knack” to be an individual thing that can’t be specified. But, the TWI and standard work approach stress that “knack” can and should be standardized and can therefore be improved.)

My team leader observed what I was doing. He watched for a while, his brow steadily furrowed, and soon asked me why I couldn’t do it as I had been instructed; that is, according to the standardized work instructions. I explained that it was easier for me to do it my way. He listened, unconvinced, and observed me awhile longer. Then, he asked me to try it the “right way” again, explaining that he was fearful that I would hurt myself if I kept up with my improvised repetitive motion over and over day after day. Perhaps my way seemed easier to me at the time, but the position I was maintaining to do the work would surely cause strain, which would injure me over time. I complied with his instructions and tried again doing the job the standard way, but, sure enough, I found it very hard to perform the work that way. So, I explained that I would really have to go back to doing it my way. He said, OK, for now, again clearly unconvinced, with concern on his face, and again stood there observing me as I did the job.

Then, as I did the job as he continued to observe, I began to feel his observation, and my awkward work slowly attracted a crowd. Before long, the group leader (my team leader’s boss), some adjacent team leaders, and others I didn’t know were all standing there, watching me work. I didn’t have time to worry much about it. My takt time and cycle times were about 56 seconds, and I usually had no extra time to chat or divert my attention as I did my job. (On average, vehicles would pass through that had different option content, so some would require well over 56 seconds, some less — the cars were arranged in a sequence, a heijunka sequence that assured that two high-content vehicles never succeeded each other. There would always be a lower content vehicle that required less time in between.)

Then I noticed that the group of observers huddled, akin to an American football huddle, engaged in intense discussion. Then, as they broke their huddle, my team leader tapped me on the shoulder, instructed me to step aside, and took over my job. He and the others had come up with a NEW way to do the job, neither the original standard work way nor my improvised method, which they all agreed would injure me if I kept it up. My team leader tried out the new procedure, and I joined the others in observing. When the new method seemed to work to his and the others’ satisfaction (many heads nodding approval, but still many furrowed brows as well — this was important stuff), he asked me what I thought. I gave his suggestion a try. Sure enough, the new procedure worked for me and to the satisfaction of the impromptu task force. The other observers had included, I discovered later, a safety specialist.

So, safety comes first, and there are aspects of successful work design that don’t necessarily appear on the various standardized work worksheets. Simply, the team leader (frontline supervisor) must understand the work deeply. But most importantly, first, we must observe the work closely to ensure it is safe and effective. Then, we’ll work on efficiencies, improvements, and other problem-solving. And, beginning to end, we are going to … observe the work … very … closely.

More on Leaders

I’ve been discussing the key role of the frontline supervisor, but there also is a role here for senior leadership. Too often, standardized work is viewed as one of those mundane things and is taken for granted. People assume that standardized work is working, and if it isn’t, well, people should just do their jobs better.

But, everyone has a role to play here. Engineering needs to design work that is easy to perform in a standard way and easy to improve. Middle management needs to support the frontline supervisor, ensuring they have the time to support the workers. When I worked at the Corolla plant in Toyota City, roughly half of the team leader’s time was made available to help his team members when they got into trouble. And he had only five or so workers to support. So, here is where you should be asking yourself here, “Do we make that kind of support available to our workers?” As I visit companies, it is very rare that I see this kind of commitment to support the frontline supervisor in supporting the worker.

At some point, every high-level objective comes down to a matter of how someone on the front lines performs their work …

Senior managers need to take the time to understand what standardized work really is and how it is nothing if not a mechanism to enable them to achieve their corporate objectives. At some point, every high-level objective comes down to a matter of how someone on the front lines performs their work — this is where, as the saying goes, the rubber meets the road. Until it’s reflected in someone’s standardized work, any corporate objective or initiative is just talk or words on a piece of paper.

So, we must take responsibility to ensure that the worker learns, is supported, and has every opportunity to complete the standardized work every time he or she performs the work. Providing that support is the role of the leader: Much less policing of compliance to enforce standardized work; much more support to enable success.

Standardizing Non-Standard Work

Now that we’ve established a baseline understanding of basic, Toyota-style, standardized work for production workers, what about standardized work for non-standard work?

This topic is less a matter of a “here’s how Toyota does it” and more of a question to explore together. I think of standardized work in three levels (this is similar but different to the Toyota view):

- Level 1 – repetitive production-type work, which is the type of work we’ve been exploring in this column

- Level 2 – supporting repetitive work, which we considered in the section “Don’t Forget the Role of the Leader/Manager.”

- Level 3 – knowledge-based or service or project-based work, for which success is still a matter of

- Timing

- Sequence and content (including “knack”)

- How much “stuff” is needed to complete the work

- Output

No matter the type of work, standardized work is all about … establishing conditions in which PDCA is possible, then carrying out structured learning and improvement cycles.

No matter the type of work, standardized work is all about plan-do-check-act (PDCA), establishing conditions in which PDCA is possible, then carrying out structured learning and improvement cycles. That is called science, the scientific method. Do we think science isn’t creative? Hah — perhaps it often isn’t, but it should be!

Standardized Work is the Basis for Kaizen

So, what shall we make of this discussion of standardized work? Two motivations drove me to write a bit extensively about standardized work. The first is to emphasize that standardized work is a fundamental building block for any lean system but remains woefully misunderstood, misapplied, and often disregarded. I think one reason it’s neglected relates to my second motivation.

Second, I want to emphasize that well-designed standardized work will recognize all the social factors that go into producing good quality in a repeatable way. Poor work design could easily lead to a mistake by the worker and a subsequent quality failure. The work design must produce the required output, as defined by the technical requirements, the specifications, and as specified by the engineering design of the product. That comes first. But, the work design must also include the “human factors,” the considerations that make it possible to do the job the right way and even difficult to do it the wrong way.

These two points bring us back to the thesis that the technical/process side and the socio/people sides of the standard work equation are equally important. You can’t separate them.

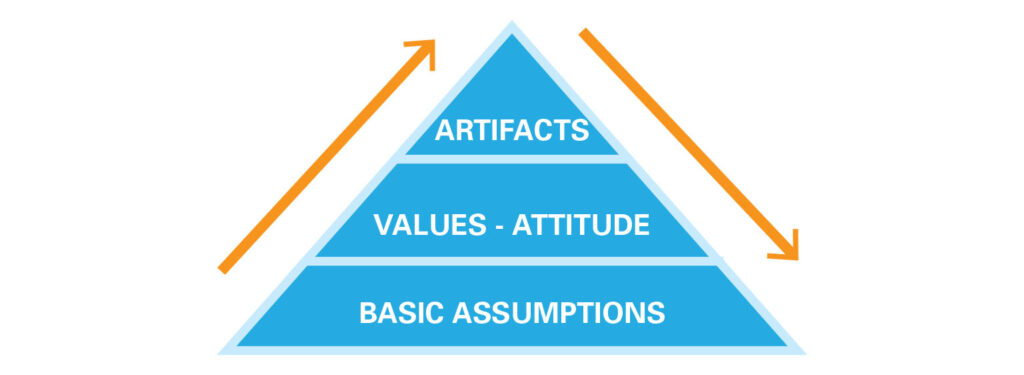

Look at your standardized work and structured improvement process (kaizen) — that is where you will find your culture!

Intro to Lean Thinking & Practice

An introduction to the essential concepts of lean thinking and practice.

See the need for more support from upper management to the supervisor and definitely more support from the supervisors to their departments. They need to be more involved in driving these standards in their departments, not working on production.