New Balance at a Glance Boston, MA, headquarters Makes and markets width-sized performance footwear and apparel for women, men, and children Privately held Commitment to domestic production based on lean principles; three plants in ME, two in MA $1.55 billion in 2006 sales in 120 countries Employs nearly 2,800 people globally Wholly-owned subsidiaries in the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Canada, South Africa, Brazil.

Every Wednesday at noon managers and employees at the New Balance athletic shoe plant in Lawrence, MA, meet in a training room above the shop floor to devour lunch and problems.

During a recent visit, front-line supervisors and flow coordinators (a post similar to team leader) from the plant’s four value streams took turns giving presentations to plant and senior management over a company-provided lunch of baked ziti, chicken, and salad served on paper plates. There were no fancy PowerPoint presentations. Employees used storyboards — white cardboard posters bearing pictures and hand-written data gathered from their work areas — to explain how they were using the plan-do-check-act process to attack key problems on the shop floor.

“They pick one of the problems they’ve had, they state the business case for solving it, and they explain what they are doing for correction,” explained John Wilson, executive vice president of manufacturing, as the presentations began. It took about 30 minutes for the four teams to make presentations to the room of about 25 people. (Learn about the executive’s role in a lean transformation in the Lean Leadership Series Q&A.)

The Red Value Stream’s report was typical. From time to time, shoes were being embroidered with the wrong color thread, leading to rework. After careful observations, the team believed it had identified the root cause: thread and needle combinations varied from sewing machine to sewing machine. For example, needle type “A” could have red thread on one machine and black on another. As operators switched machines and needle types based on the shoe type being made, it was easy to use the wrong color thread. The team devised a standardized system so the same type of needle would have the same color thread on every embroidering machine. Team members said they were in the process of implementing and testing the proposed solution and would report back on the results at the next meeting.

Seeking Higher Performance

When it began a lean transformation in 2003, New Balance, the only athletic shoe manufacturer that still makes some products in the U.S., focused on using lean tools to improve product flow through its five New England plants to retailers and final customers. Next, with help from the Toyota Supplier Support Center, management began organizing the change effort around problem solving and process improvement to create a culture that would engage the workforce while moving the company to higher levels of performance.

“The early lean implementation work like creating flow and producing to takt time improved the output of the factories, the availability of products, and obviously costs as well,” Wilson said. “We grabbed the low-hanging fruit — the problems that were relatively easy to solve. To get at the fruit that was not hanging so low was more challenging. To take that next step, we started organizing ourselves around problem solving to get employee involvement, buy-in, and culture change. Those are the keys to driving lean further.”

Problem solving also helped Lawrence’s 215 associates understand why lean principles and tools such as standardized work, takt time, and kanban were important. And it improved the quality of work life by giving associates a way to solve their own problems, Wilson noted.

Lean Education

The company laid the ground work for the renewed lean transformation, which it called New Balance Executional Excellence or NBEE, by developing two short workshops to train associates on the basics of lean and waste detection, respectively. It also made a promise. “The cardinal rule we made when we started was that that no one was losing his or her job,” said Wilson. “If people leave and we don’t replace them that are a different story.” When productivity gains freed people, they were re-deployed to other areas. As the lean transformation progressed, people who couldn’t adapt were moved but not fired. Over time, many came around to the new way of working.

“We also explained to people what we were trying to do and that we needed their input if we were going to be successful,” said George Skafas, production manager. So the early ground work included asking associates to submit improvement ideas in writing, but at first management didn’t require ideas to be implemented. Associates submitting ideas had their pictures and ideas hung on a “wall of fame” in the cafeteria. As their problem-solving skills grew, associates had to implement their ideas, too. Within a year or so, each associate was averaging three implemented ideas annually.

Managers, including senior executives, learned lean principles, as did finance and product development staff. Executives’ 30 hours of instruction included Toyota Production System (TPS) concepts, lean product development principles, and observing a value-stream mapping event in sales. Factory management got 100 hours (not including self-study) of training in such areas as TPS, strategy deployment, the plan-do-check-act problem solving cycle, standardized work, and lean leadership. Small laminated cards identifying eight deadly wastes carried by all associates and managers reinforced the training. (New Balance added “unused creativity” to the traditional seven wastes. See glossary below.) The training fostered a different way of thinking. Instead of directing solutions to problems, managers would “go and see” the problem and work with associates to establish a point of cause and a hypothesis for implementing a countermeasure.

Most problem-solving activity begins at daily shop-floor meetings. Flow coordinators in each value stream meet with supervisors at 7:30 a.m. and 11 a.m. for production meetings at the stream’s problem-solving kiosk. They also meet with quality assurance engineers on the shop floor daily between 9:30 a.m. and 10 a.m. to review quality issues. “We try to keep the meetings brief,” said Skafas.” We try to speak to the facts.”

The kiosk is a compact stand where critical information is kept, including preventive maintenance schedules by machine, a binder for tracking problems and countermeasures, and another binder for holding standardized work audits. During twice daily audits, each team’s coordinator uses a check sheet while observing whether operators are following the step sequence for their processes within takt time. Supervisors spot check that the coordinators’ audit sheets are up to date.

At the kiosk meetings, coordinators and supervisors quickly assess the audit results and other key indicators such as downtime, quality, and production volume, looking for abnormalities. For example, within the production cells of each stream, supervisors record hourly output on white boards. If a target is missed supervisors and coordinators identify the reason why, and then record it as a written problem statement in the kiosk binder along with planned countermeasures. They work with employees to come up with a solution during the shift. Results are charted and reviewed at subsequent meetings. To sustain improvements, follow-up audits or reflection times are often scheduled.

“You have to become much disciplined and react very quickly when you fall of the pace, said Wilson.” Last year, Lawrence, was consistently around 99% in achieving its production goals. “We never cut the schedule by even a pair of shoes.”

If necessary, production is made up on overtime at the end of the day, but it’s a premium option that management tries to avoid by consistently producing to takt time, the rate of customer demand. “We’re working at stabilizing the value streams, getting to complete flow, and problem solving the issues we have that knock us off takt time,” Wilson said.

Identifying Problems by Business Needs

Besides day-to-day problems, variations from the plant’s business goals generate problem-solving activity. A strategy deployment matrix (see glossary) that aligns improvement efforts with business goals, guides coordinators and supervisors in prioritizing what problems to tackle when hold kiosk meetings. The matrix takes five top-level corporate business goals, such as “dramatically decrease product cost” and “significantly increase product quality” and aligns them with specific manufacturing activities at each plant along with assigning responsibility to functional area managers. For example, a quality manager would have a detailed list of activities to meet a goal of improving quality significantly.

“Deciding what problems to work on has to be an intelligent decision based on business needs,” said Skafas. “People are told to see a problem through to resolution once they begin working on it.”

The red value stream’s project to standardize needles and thread colors was a case in point. When associates had to rework a case of unfinished shoes because the wrong color thread was used, a team observed the existing production process to identify the root cause and propose a solution. “It usually becomes apparent what you can do today to put a countermeasure in place,” Wilson said.

The new problem-solving focus has bottom-line benefits, like helping the plant achieve a goal of boosting daily output on all four value streams from 35 cases of finished shoes to 50 cases. The pilot project “took us 17 days and 25 ideas” to achieve the jump in output, Wilson noted. And when metrics indicated that progress was needed to improve material cutting efficiency, an important objective, plant management asked a team to examine the problem and make suggestions.

Another objective was to increase the capacity of a process for gluing shoe components together in final assembly. During observations and time studies, flow coordinators and supervisors realized they were losing 3 to 4 seconds every time a glue spray gun was cleaned. Two teams working on the problem came up with about 10 new procedures and devices to speed up cleaning the gun to ultimately achieve a 100 case-per-day spraying capacity.

The Bad Old Days of Batching

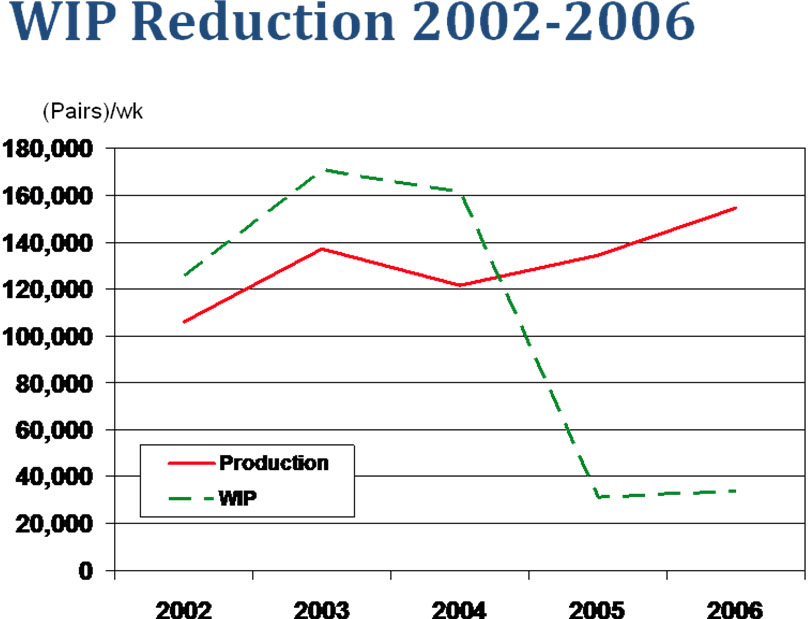

“Before we started this lean journey we had nine days of work in process on a good day,” said Wilson standing on the Lawrence plant’s shop floor near a value stream making walking shoes. “It took us nine days to make a pair of shoes. We were in full batch mode. Now it takes us, on average, four hours.”

Batch mode organized production traditionally — by departments specializing in one type of operation and that were spread over multiple floors of the building, a former textile mill. Big batches of partially completed shoes were moved from floor to floor — from cutting, to prefit, to computer stitching, to hand stitching, to lasting, — through all the production steps — and finally to packing. For example, as many as 60 people in the prefit department worked one floor beneath the production floor, adding components, labels, and embroidery to uppers.

“We had piles of inventory between floors, between departments, and between operators,” Wilson recalled. Producing and moving big batches of partially completed shoes took a lot of time, hid quality problems under piles of inventory, and lengthened lead times, an especially

perilous problem in the retail shoe business where styles get hot and cool off quickly. The negative effects of batch production were compounded by a pay system based on piece work that encouraged operators to produce as much as possible, adding to the piles of work-in-process (WIP). (In 2000, the plant completed a migration to hourly pay that includes some incentives.)

One-pair Flow

Today, the production floor is arranged in value streams making a family or products sharing similar processing steps. “We created flow by bringing the right quantity of operators and machines together to enable us to make and move one pair of shoes at a time,” Wilson explained.

On one side of the plant’s center aisle, a value stream uses pre-made uppers from overseas suppliers to create finished shoes. On the other side, three value streams make “cut-and-stitch” shoes from scratch. In all the value streams, operations that once were separate departments now are arranged side-by-side in tight U-shaped cells. Electronic displays in the value streams indicate the takt time and compare scheduled production to actual.

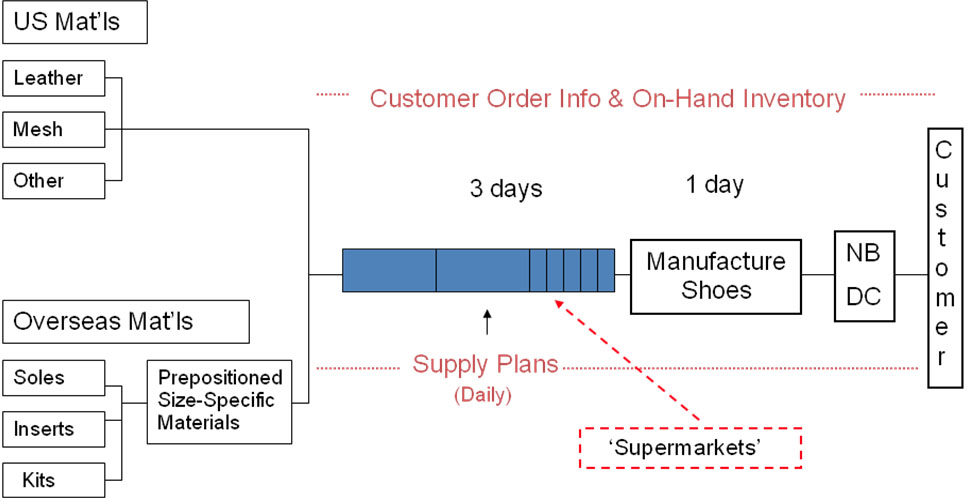

Work begins when the production office on the shop floor, using information about what retailers are ordering from the company’s distribution center, issues work orders designating the materials required to make the needed shoe types, sizes and widths. New Balance is unique among athletic shoe makers because it produces shoes in multiple widths, not just one or two as most of its competitors do. The work orders, which are scheduled to switch to an electronic format, go to the floor below where raw goods, such as pre-made uppers from overseas suppliers or bolts of materials from domestic ones are kept. The material needed for the next production run is organized on a cart and brought upstairs to die cutting.

When manufacturing “cut-and-stitch” styles, the first step is to die cut rolls of raw materials to shape. The die cutter is the shoe industry’s equivalent of the metal-bashing industry’s blanking press. It’s a big expensive machine serving multiple value streams. There’s no economic sense in cutting material for just one pair of shoes at a time.

Materials handlers deliver the rolls of materials hourly by cart to die cutting. Handlers, responding to kanban signals, deliver the various die cut parts every 10 minutes tooperators. Shoes move through production one pair at a time, with one pair between stations, as they are stitched, cut, glued, and formed into finished pairs, put into shoe boxes, then loaded into cases for shipping at the end of the value streams.

On a recent day, a production operator at a sewing machine periodically was waiting a couple of seconds for the operator at the previous station to hand him shoes. Wilson noted that as part of creating a problem-solving culture, associates have learned to stop when there is no work, rather than building ahead or finding something else to do.

“We want to see where a problem or bottleneck is,” he explained. In this situation, the area flow manager will perform an audit to see if standardized work was being followed at the operations. “She’ll be able to determine what the problem is,” Wilson said. With batching between steps, finding a problem or bottleneck was “like looking for a needle in a haystack.” Ultimately, the objective is to have flow coordinators work with individual operators in real time to solve problems. “The goal is to tackle problems, flesh out ideas, and make hundreds or thousands of improvements during the course of the day,” Wilson said.

Lean Fulfillment Stream

The switch from large batch production to one-pair flow has freed so much space that raw material storage is moving next to production from the floor below. Less inventory space means more space for ultimately adding equipment to increase domestic shoe production. Some of the former inventory space downstairs already is being used for “learning centers,” production cells where New Balance trains new operators and tests new products. “We want to make sure the product is engineered for manufacturability so when a new style hits the manufacturing floor we can hit the takt time 100% right from the first day,” Wilson said.

Domestic inventory for New Balance’s five domestic plants is replenished several times daily in small lots by nearby suppliers. Several key suppliers are on an electronic kanban system. The company is in the process of transitioning all suppliers to the system.

Managing the international inventory, primarily soles and uppers, based on lean principles is “a little bit more of a challenge,” Wilson said. “Getting Asian factories to support us with very quick response is going to take us four or five years.” New Balance has started helping Asian suppliers make the transition to lean, shrinking lead times from 17 or 18 weeks to 10, including five weeks of transit time. New Balance maintains a safety stock of raw materials and uses MRP to plan long-term raw material needs.

“There’s no doubt that by shrinking our lead times we’re collapsing our suppliers lead time so there is some commitment of raw material inventory that we make but raw materials have the least value,” Wilson explained. “It will be a lot more cost effective for us to obsolete some raw materials if we have to, than it would be to obsolete finished products.”

In contrast to New Balance’s cellular layout, a typical Asian shoe factory uses long straight production lines staffed by 80 to 100 people, Wilson said. Their output is equivalent to the output of 15 people in Lawrence thanks to the lean manufacturing improvements and selected automation. Labor at a shoe plant in China costs $0.50 per hour compared to $14 at a U.S. facility, not including benefits, according to Wilson. “We’re paying a lot more in Lawrence but we’re significantly more productive,” he noted. He estimated Lawrence improved productivity by at least 25% between 2003 and 2006.

Connecting the Business and Lean Manufacturing Models

For many athletic shoe companies, becoming more competitive meant moving all operations to Asia. So why hasn’t New Balance moved?

“There are two reasons for that,” explains Wilson. “One is that owners Jim and Anne Davis believe it’s critical for New Balance to be a manufacturer as well as a marketer.”

The other reason stems from the company’s business model. Unlike most athletic shoe companies, New Balance doesn’t pursue endorsements by big-name athletes, proudly preferring its “endorsed by no one” tag line. (The company notes that it uses world-class athletes to develop and test products, just not for advertising.) And unlike most athletic shoe companies, New Balance makes shoes in up to six different widths from a narrow 2A to a broad 6E, based on a belief that shoes that fit better perform better. The company’s business model combines this commitment to performance over fashion with a commitment to providing retailers with high service levels. The impact on manufacturing is significant.

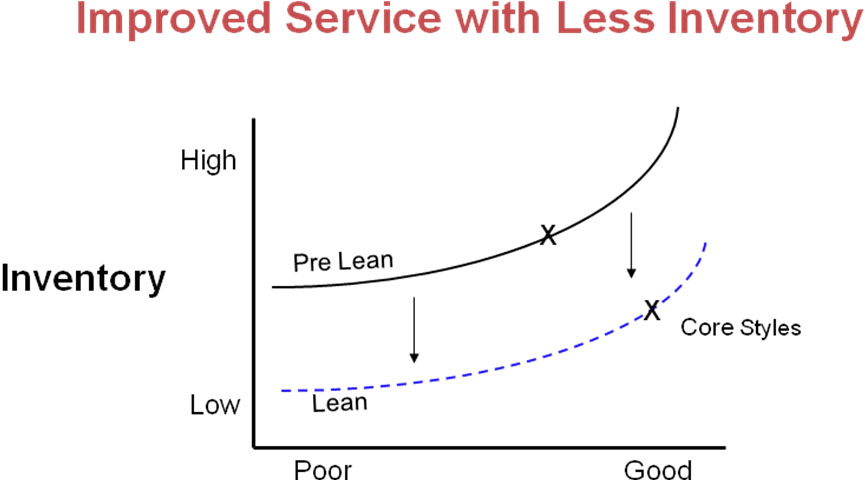

Wilson, pointing to the 992 model shoe he was wearing on a recent day in his office, explained. “We make this shoe probably in about 80 stock keeping units (SKUs) because we make it in AA, B, D, EE, and EEEE widths. And we make it in varying sizes, beginning around 6 and going up to 17. So, maintaining a high service level would require us to have an extraordinary amount of inventory to provide all those variations. Typically if you have one width in a shoe, which is what most all of our competitors do, you’re talking about 17 or 18 SKUs at the most. In our case we have about 80 for the 992. For other shoes, the range can be as low as 40 SKUs or as high as 82 or 83. The median probably is in the low 60s range. So every one of our styles is equivalent to four styles of the competitions. Plus, we’re doing a lot of business with a lot of smaller retailers and they don’t have a lot of buying power or space for a lot of inventory.”

These retailers replenish inventory in small lots because they have to and because New Balance has been educating them and larger “big box” retail stores about its lean-inspired manufacturing and distribution capabilities to rapidly replenish its “core styles.”

The vast bulk of New Balance’s product line is divided between what it calls “core styles” and “in-line styles.” (A much smaller third category is specialty made-to-order styles.) New Balance promises retailers that it will turn around orders for core style shoes in just 24 hours. “We will ship it in 24 hours from receipt of order,” Wilson said.

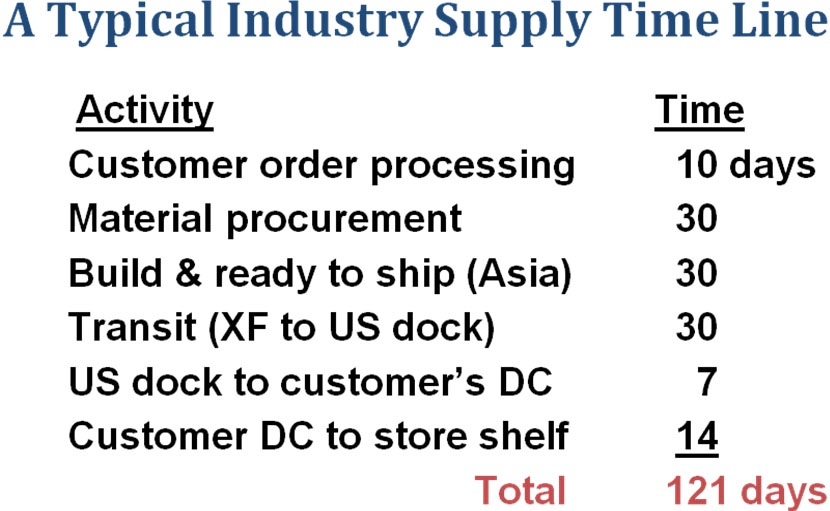

For competitors, the lead time from Asia could be as long as 121 days, which means a shoe style could be out of fashion by the time it arrives in U.S. stores. “Lowest product cost cannot be the major criteria for determining manufacturing location,” Wilson said. “If we are going to succeed with U.S. manufacturing, we must connect the company’s business model and the manufacturing model. Because we have manufacturing capability here, we can turn around and ship an order in a day then turnaround and replenish that within two days. This also frees up money from inventory and allows for additional styles to be placed with retailer.”

To meet the 24-hour promise, New Balance makes core styles at its domestic factories. “The management team felt to achieve the service and quality we were looking for in our premium products, we had to manufacture those products here in the U.S.,” Wilson said. It splits manufacturing of in-line shoes between them and Asia. Overall, the company makes about 25% of its shoes in the U.S. “To be successful, we blend production between the U.S. and Asia to re-curve inventory,” Wilson said. “Averaging the costs allows us to achieve our goals.”

In general the “cut-and-stitch” styles are manufactured in the U.S., accounting for about 75% of U.S. production. The remaining 25% of U.S. production are lower-priced shoes built from pre-made uppers imported from Asian suppliers. Having the flexibility to rapidly replenish both types in small lots from U.S. plants gives New Balance the capability to respond quickly to demand without carrying excess inventory.

The most popular domestic styles have annual inventory turns as high as 18, but Wilson believes domestic plants can generate at least 24 turns of finished goods due to the lean production improvements. “We’re working towards that goal but it’s going to take us a couple of years to do that consistently, he said. ” We’ll be able to change on a dime to what customers are buying.”

Production planners see what customers are buying by electronically monitoring what shoe styles, sizes, and widths the distribution center has shipped to retailers during a one to five day period. They schedule production to replenish what’s been shipped, maintaining a level of finished goods to provide a 98% “at once” availability to retailers.

The ideal level of finished shoes inventory is as low as possible without running out. “It’s easy to have 100% availability if you’re carrying 200 days of supply,” Wilson said. “We’re trying to keep finished goods inventory down to 22 days or even lower.” Currently some styles are made daily. Most are made weekly, but the company is gradually moving these to daily production as the lean transformation progresses. Planners adjust inventory levels to account for demand spikes in peak months or the introduction of new styles.

“We’re going to be making smaller and smaller quantities because it allows us to level out demand to eliminate the peaks and valleys of building inventory,” Wilson explained. “We have a lot of activities going on that will culminate in great, great capability and a competitive advantage.” For instance, the sales team is working with retailers to have them place smaller, more frequent orders that go directly to stores instead of placing large orders that go to retail distribution centers. “It will be more efficient for us and the retailers,” Wilson said.

| New Balance Box Score for the 990 Series Shoe | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2006 | |

| At-once availability (core styles) | 84% | 98% |

| Inventory turns (core styles) | 3.5 | 13 |

| Time to make a pair of shoes | 9 days | 8-12 hours |

| New Balance | Competitors | |

| Order to Ship (2,168 SKUs in core styles) | ||

| 24 hours | 121 days |

Managing on Purpose with Hoshin Kanri

Learn how to develop strategy and build alignment.