I just left the Lean Product and Process Development Exchange conference in Durham North Carolina. It was alive with lean PD practitioners sharing results of their experiments in the art and science of improving (lean) R&D. We heard experiments into improving the way people map and integrate their innovation work, methods to teach engineering principles, and ways that joy and the human side of work life could be driven by better thinking.

A second thread running through the conference was a reflective question about the scope of the lean product development field. What is the purpose of lean PD? Where are its limits? Who plays, and what is “out of bounds?” Such an identity “crisis” is thrilling to see. It is the hallmark of an emerging science.

When material science and genetic engineering emerged, researchers struggled to carve out their own identity separate from physics and chemistry and differentiated from the regular biology and engineering – wonderful staid sciences that no longer kept pace with the needs of the science around them. This crisis of identity was/is the marker of great innovations to come.

That said, it never hurts to have a little help in corralling all of that creative energy. If we can develop a framework to put our new lean product development energy into useful practice, we will accelerate our own art and science. To this point, I propose that we use lean thinking itself to help us along. We might begin by asking, “What is the purpose of R&D?”

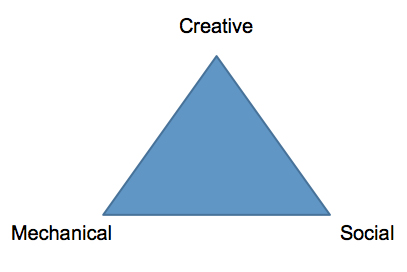

In my view, this is straightforward. The purpose of R&D is to create valuable knowledge faster than others, that is, to innovate ahead of competitors. What then, is innovation? Innovation can be broken down into three required acts. A creative act generates a (potentially) valuable idea. That idea is only useful if proven so through a mechanical act the lawyers call “reducing to practice.” But so far, we have only invented something. For an invention to become an innovation, other people must adopt it. This requires a final social act. From these three elements, the creative, the mechanical and social, we can formulate a framework, the innovation triangle:

Lean manufacturing, of course, is powerfully effective in the mechanical realm. Putting laboratories together that efficiently process experiments and tests has become a minor industry, and with good reason. “Lean labs” can radically reduce testing time and laboratory costs. However, every researcher knows this is just the tip of the iceberg. No matter how efficiently run, a bad experiment results in nothing of value.

Lean PD has been expanding our thinking beyond the mechanical, and there is much of value to be gained by the knowledge already created. Set-based engineering radically alters the effectiveness of our reductions to practice. Meanwhile, concurrent engineering and product development value stream mapping create clear paths linking the socio-mechanical aspects of R&D. Reduction to practice is covered quite nicely by many established lean thought leaders. Take A3 thinking, for example, and by lean PD thinking, trade-off curves, and engineering sets.

But we are just at the beginning. There is an entire field of study about creativity and what makes us creative, but the field is in something of an organizational shambles. The terrific science and management art in this field is mixed in with a mountain of junk science and management voodoo. Even if you can glean nuggets from this pile, those nuggets are often without real world practicality, a clear way to integrate them into a working, beating business system. That is the hallmark of lean thinking. For me, this is our opportunity to create an applied science of improving creativity.

Similarly, while set-based concurrent engineering and value stream mapping help enormously in internal organization of research, we need to think: what can we do to innovate around uptake? In other words, how to help people pick up these concepts. So many brilliant inventions fail, only to be revived by someone else in a later decade by someone who found the link between invention and the customer’s imagination.

As a lean community and a product development community, we have much exciting work ahead of us. I look forward to contributing to LEI’s new effort to gather lean product and process development thinkers and practitioners together at leanpd.org. And I look forward to hearing about your experiments. What succeeded and what failed, why those successes and failures occurred. And finally, I anxiously await the new tools that you design, prove and make part of the LPPD innovation work itself.