Be among the first to get the latest insights from LEI’s Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) thought leaders and practitioners. This article was delivered to subscribers of The Design Brief, LEI’s newsletter devoted to improving organizations’ innovation capability.

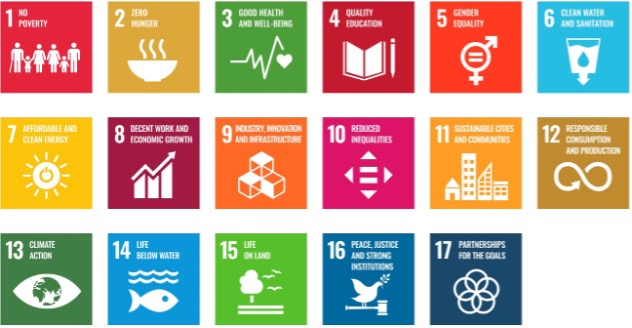

In 2015 the United Nations and its member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The framework provides a true north for the well-being of humanity and the planet. If we think of the planet as our common set of limited resources and society as our common human enterprise, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) define our global hoshin.

We may not be able to contribute to every SDG in our limited work sphere, but Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD), and lean at large, certainly help to build a better, less consuming, less damaging society. With that aspiration in mind, companies, including Toyota, have started to incorporate the SDGs into their corporate strategies.

Now, what have over four decades of LPPD taught us about sustainability?

1. If we observe how customers use our products, we can learn a lot about the waste designed in them.

Whether in industry or services, our mental model is a design-to-delivery process. In circular economy parlance we call this cradle-to-gate. We are obsessed with design intricacies, marketing options, production issues, and logistics. But once delivered and paid for, we pay little attention to our products. We often ignore the difficulties customers encounter when using them and have, until recently, paid little attention once they reach the end of their lives or are discarded. We mask declining sales and lost customers by frantically launching new products or expanding to new markets through mergers and acquisitions.

One of the best examples of this today is Shein, the world’s largest clothing retailer. On average, the company releases a staggering 6,000 new styles per day and relentlessly markets them via social media influencers. The message to consumers is to buy lots of cheap clothes, wear them once, throw them away, and start all over.

On the other hand, good products or services, which are continuously improved and enhanced based on usage feedback, fully satisfy customers. This fosters brand loyalty and results in comfortable profit margins.

Observing how customers reuse products can reveal powerful insights. Take this golf pushcart example: initially, the customer was satisfied with his purchase as the pushcart was light and easy to fold into his car’s trunk. However, issues arose in winter. The customer had to stop every three holes to clear mud stuck between the wheel and its fork. This problem stemmed from the fork’s design being too close to the wheel, which did not account for the mud a golf cart could collect on a soaked golf course. Consequently, the customer discarded the cart soon after and moved to another brand.

This simple example illustrates the importance of the design phase. Decisions taken at that stage will massively impact the product’s overall cost and its environmental footprint. LPPD tools and concepts offer many opportunities to think about those consequences and how to resolve them in development.

Our mental framework must evolve from a cradle-to-gate approach to a cradle-to-cradle one. This means thinking about how our decisions impact a product’s end-of-life, such as options to reuse, recycle, or upcycle in its overall package.

2. We can massively reduce our resource consumption if we learn to see waste in production and logistics.

There are endless opportunities to reduce our impact in production and logistics. Here are just a few challenges to consider:

- Have we recently revised our purchasing agreements to check whether our demanding specs are not creating undue waste? For example, think of the uniformly sized and shaped fruits and vegetables in our stores. How many were discarded to achieve those wondrous rows of perfect oranges?

- Can we learn from assembly issues encountered with existing products before designing new versions? An easy, intuitive assembly should be the goal. Think of Ikea: their easy-to-assemble-at-home models were a winner, and the same principle applies to manufacturing!

- Can we optimize the number of shapes cut from a single sheet of metal or fabric to reduce scrap?

- Can we use returnable containers rather than cardboard boxes?

- Can we reduce the space we use rather than rent or purchase a new warehouse?

- Can we achieve the same processing results using less energy?

- Can we recycle the water we use and collect and retain rainwater?

- In batch production processes, such as oven curing, can we use kaizen to arrange parts inside the oven more efficiently and fit more into each batch?

- Can we design equipment that uses gravity and simple mechanisms like springs – versus electricity – to move parts? Toyota calls this karakuri and uses it prolifically.

- Are we sure the total cost of ownership manufacturing in far-away, low-cost countries is not more expensive than manufacturing closer to home?

- Can we insource external treatments, such as painting and coating, that increase lead time and require transportation?

- Can we adjust packaging to match its contents to avoid transporting air?

Exploring these opportunities to refine production and logistics can lead to substantial reductions in environmental impact and efficiency improvements. Achieving zero waste in production is possible! Subaru’s assembly plant in Lafayette, Indiana has sent nothing to a landfill since May 2004.

3. When the challenge is complex with multiple trade-offs, aim for hybrid and modular solutions rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

Consider the complex challenge of cars. We are not ready to relinquish the comfort of vehicles that can take us from point A to point B whenever we wish. And we are not ready to stop making online purchases with their cozy front-door deliveries.

We value not just their function but their aesthetics, as cars are symbols of success.

We want protection from violent crashes, but fuel economy demands reducing vehicle weight.

Given the impact on the environment, we need to move away from fossil fuels as soon as possible. However, electric vehicles raise infrastructure issues, such as managing battery lifecycles and building charging stations.

In addition, vehicle use varies widely, from urban commuting to outdoor exploration, long-distance deliveries to last-mile trips, and from business travel to family outings.

The European Union thinks we can answer this challenge with a single solution: ban sales of gas-powered cars from 2035 onwards.

Toyota, on the other hand, is taking a set-based approach to the problem. Depending on the vehicle size and the driving distance, they believe the optimal solution will be different. Electric vehicles would be best for small urban commutes; hybrid powertrains would suit medium to large cars for those who commonly travel long distances; and long-distance haulers, such as buses and delivery trucks, would perform best with hydrogen. Consequently, Toyota is working on all three solutions.

Toward Sustainable Innovation

Embracing the 17 SDGs as our shared guiding principles and employing the powerful tools of LPPD can guide us toward a more sustainable future. This journey demands a new way of thinking about product development, but the rewards will be a world where prosperity and environmental responsibility go hand in hand. But we need to remember that automation and AI collect data far faster than humans, perform recurrent tasks flawlessly, detect problems humans cannot, and take on heavy burdens. As we test new ways of thinking and adopt these powerful tools, let’s retain our kaizen spirit and scientific thinking. That is what nurtures societal improvement and generates sustainable innovation.

Designing the Future

An Introduction to Lean Product and Process Development.

I find this article very inspiring and current. It highlights the importance of Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) in sustainable product design. I particularly like the idea of moving from a cradle-to-gate approach to a cradle-to-cradle approach, which focuses on reuse or recycling to reduce the environmental footprint. I also appreciate the reflection on customer observation and the integration of their feedback into the design process to create more suitable and sustainable products.

As a future supply chain engineer, I now understand how these principles could be applied in business. However, I wonder how companies in general can measure and assess the real impact of their sustainable Lean initiatives. Are there specific KPIs you recommend?

Hello Halm

KPIs are needed, they help to understand where we stand and whether we are making progress. But I am sure you are well aware of their risks : managing by KPIs instead of being on the gemba, focusing on one aspect because of a given KPI (for example sales) while forgetting to track another vital aspect (quality).

Nevertheless, you may want to explore the following paths :

– customer claims : few customers will actually complain, most will move to another brand unless they need you to solve the problem. Nurture the claims you receive and investigate them thoroughly, you will learn plenty about your products and services.

– A to D defect segmentation : Sam Nomura explains it, in his great book The Toyota Way of Dantotsu Radical Quality Improvement. D are defects detected by the customers, C, by final inspection, B by the downstream process, A, by the operator himself. The whole point is to bring defects back from D to A and to learn from each defect analysis.

The above is more than just counting numbers : it requires investigation with the purpose of improving and learning. Another interesting approach is the Life Cycle Analysis of your products or services : by far the best way to initiate a thorough cradle-to-cradle approach.

And, I forgot, if you think of sustainability in production, you will need KPIs pertaining to carbon emissions, water consumption, unrecycled wastes…

Very educational, if all of us have a friendly enviromental awareness we can get a better world, our life style is killing us.