Lean.

A four letter word. Rhymes with mean. When used in a sentence, it creates visions of hardship, such as getting by with less. Lean and mean. Leaning out the workforce. Doing more with less. Yet in my experience, none of these things accurately describe what lean thinking is really about. So why do they so quickly come to mind?

In 1997, our entire salaried organization participated in diversity training led by Wayne and Cynthia Shabaz. Wayne said something during the training that has stuck with me ever since: “Perceptions may not be accurate, but they are real and must be dealt with.” (Wayne, if you are out there, I was listening!). This truism can be applied broadly, but I share it here because I think it’s important in light of how lean is being applied or not being applied in organizations today.

If perceptions (about anything, lean thinking or anything else) are real – then, to use lean language, that’s part of the current state we’re dealing with. Our current state inevitably affects our ability to create a new ideal future state. So it’s worth gathering the facts, getting a real assessment about how Lean is viewed in your organization, in the minds and hearts of the people in your organization.

It’s worth asking, what’s your organization’s REAL, honest perception of Lean? If you could be a fly on the wall throughout the gemba, what would you hear? Would you hear words and phrases like engagement, problem solving, learning, “making my job better than now”, and “empowered to bring forth ideas”? Remember, we are talking about conversations at the gemba, the actual place of work where value is being created, not the few people who are participating in a kaizen event now or have participated in one in the past… not the people participating in a leadership meeting, but the masses, the people you’ve yet to work with yet who you’re looking to engage.

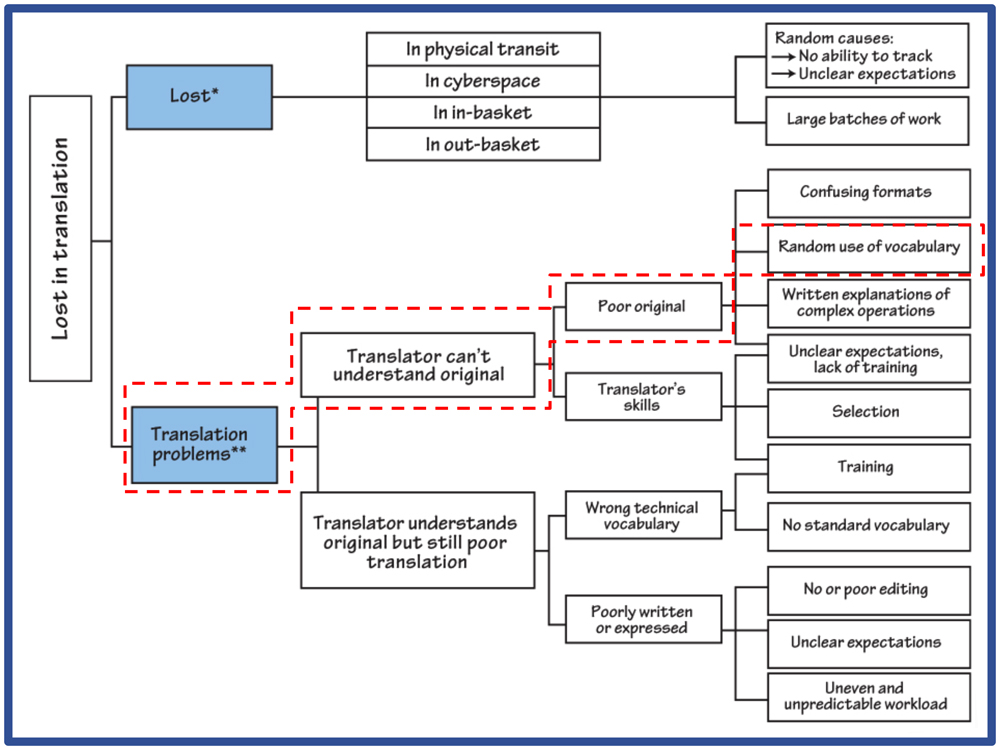

Once you’ve gathered this information (it might require some research and talking to people), try an interesting thought experiment. Take one of those perceptions and break it down using the Why process. I would suggest a tree format similar to the one in the book Managing to Learn. Once you arrive the likely root cause(s), do something about it. Let me know what you find.