The past few quarters have been brutal for the U.S. office furniture industry. The global economic decline, which has caused profits to evaporate, slashed corporate budgets and eliminated thousands of jobs, combined with general uncertainty over when things might turnaround, has furniture dealers scrambling to drum up new orders.

As sharp as the current downturn has been, Herman Miller, Inc. (Zeeland, MI) has weathered economic maelstroms before. After the IT-industry bubble burst, and the economic fallout following the events of 9/11, the company’s sales fell 40%. That downturn from 2001 to 2003 coincided with an enterprise-wide rollout of the Herman Miller Performance System (HMPS), the company’s interpretation of the widely emulated Toyota Production System. The HMPS rollout helped it respond to the steep market decline eight years ago, and laid the foundation for a completely different reaction this time around. This Lean Enterprise Institute success story shares how Herman Miller has applied lean thinking across the company, and how company leaders are leveraging that knowledge to navigate this recession, and emerge even stronger.

Because we are a much leaner enterprise today than we were 10 to 15 years ago, our ability to weather cycles is much greater.

Brian Walker, President and CEO, Herman Miller

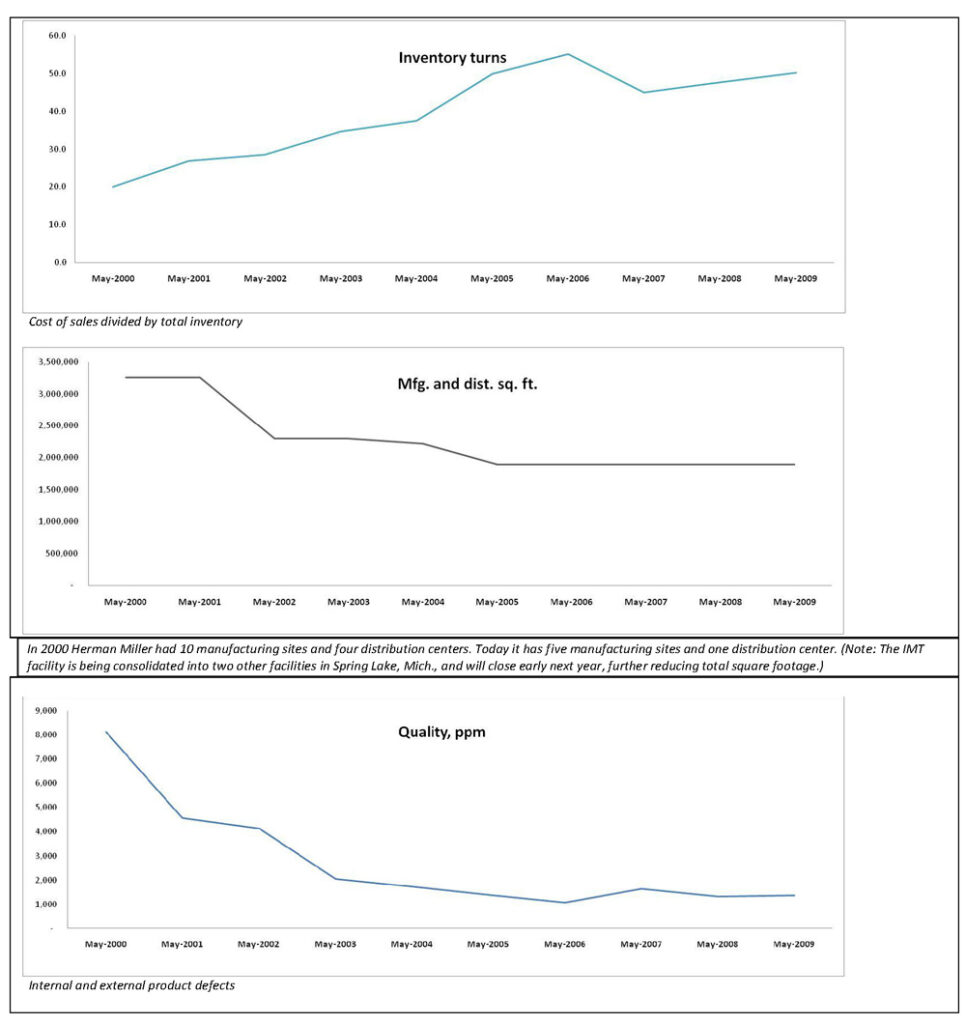

“Because we are a much leaner enterprise today than we were 10 to 15 years ago, our ability to weather cycles is much greater,” says President and CEO, Brian Walker. Walker has been with Herman Miller for 20 years. He previously served as CFO, and was president and COO until 2004. “We have a much smaller footprint in terms of asset size. We turn inventory so fast, and the balance sheet is so liquid, that when the business turns down we can adjust quite quickly and make sure that we can remain cash flow and operating income positive.”

This flexibility reflects a lean-enabled manufacturing strategy to limit fixed production costs, source component parts from strategic suppliers, and increase the variable aspect of the company’s cost structure. “In our last quarter we were down 28% or so in revenue, and yet we were still profitable and EVA positive. Being able to cycle that much has a lot to do with lean, and it also reflects our people’s willingness and ability to adjust,” he adds.

Confronting Reality

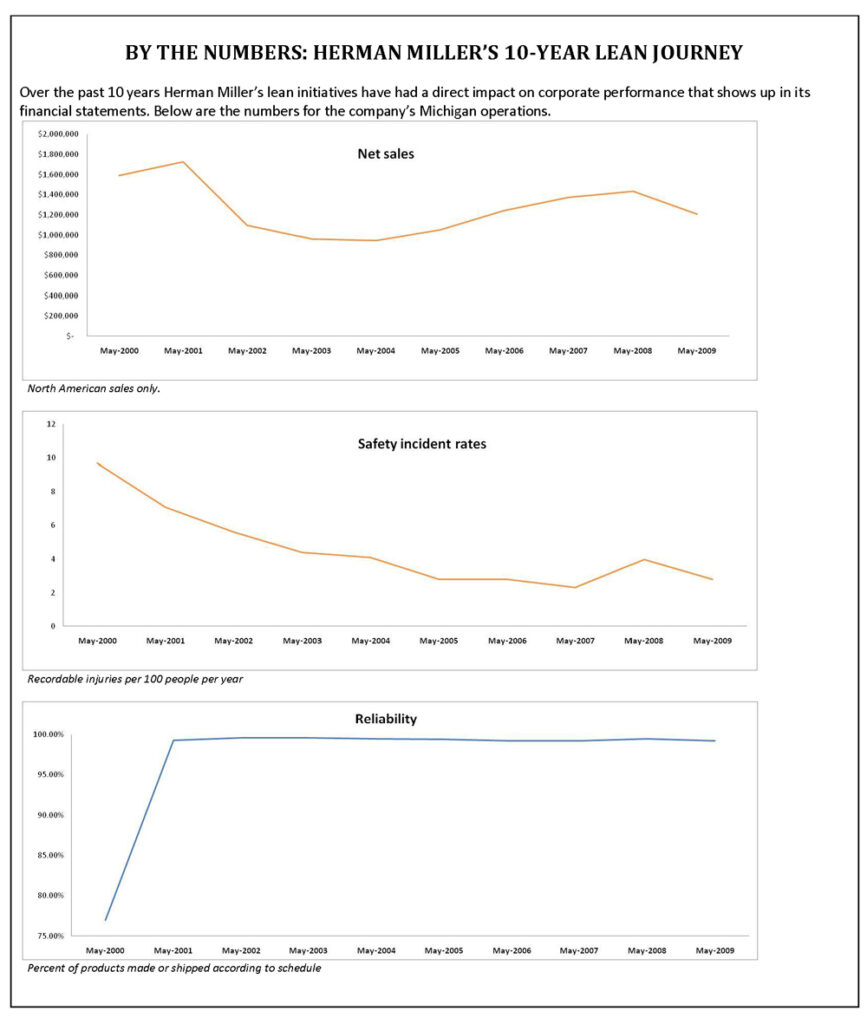

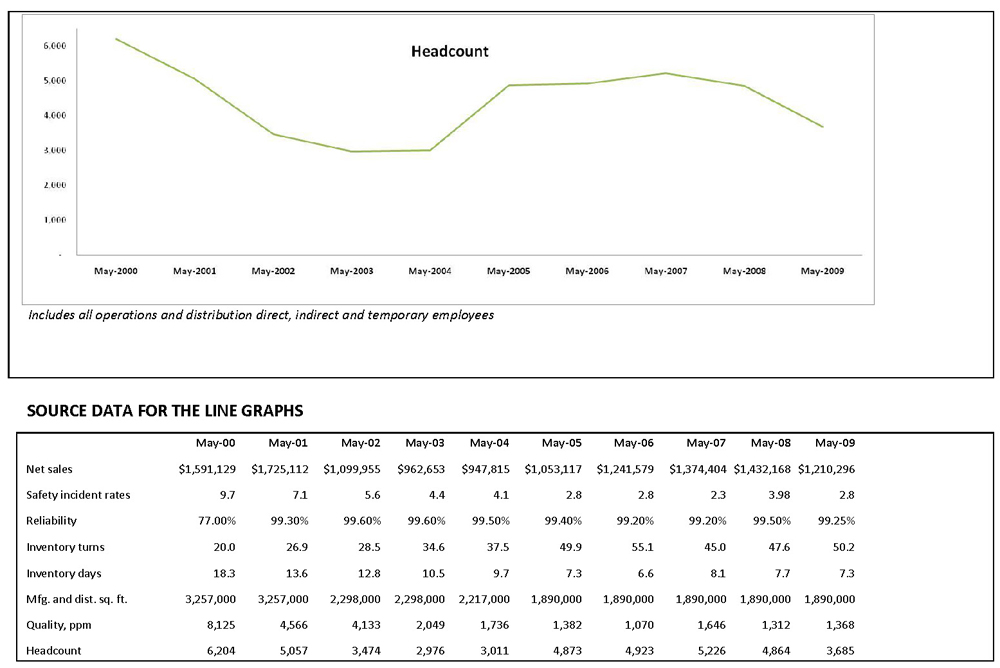

Before reviewing how Herman Miller’s embrace of lean has helped it respond to today’s realities, here are the painful facts. After climbing almost 5% to just over $2 billion at the end of its fiscal year ending May 31, 2008, the office furniture market and Herman Miller’s sales were hit hard by the downward spiral of the U.S. and global economy. Revenues compared to the previous year fell slightly in the company’s first and second quarters, then plummeted 28.5% in the third quarter ending February 28, 2009. As the company’s 2009 fiscal year came to a close at the end of May, consolidated revenue totaled just over $1.6 billion.

In response to the volume decline, starting last September, Herman Miller initiated a number of cost-cutting measures, including 1,400 voluntary and involuntary job layoffs, more than one-fifth of its workforce. The company has reduced the number of shifts on most of its assembly lines from two to one, and is currently operating on a nine-out-of-ten weekday production schedule. Company executives, who have worked hard to communicate the reality of the business situation, have taken salary cuts as well.

“We’ve had lots of pain, and lots of people have been impacted by the downturn, and that’s never easy,” says Walker. Those job losses reflect a simple calculation that matches current and projected volume to labor requirements. These reductions are not linked to the success of the company’s lean efforts. In fact, starting in 2003, total headcount had remained relatively constant as sales grew more than 50%. Prior to the downturn, employees had routinely received annual bonuses based on Economic Value Added (EVA), which generally worked out to around 6% or more of their base salary. The bonuses factored in productivity improvements and asset reduction, including square footage savings and inventory declines.

“If we hadn’t done this HMPS work, I’m afraid the name Herman Miller wouldn’t be on the front of our building,” says Director of Continuous Improvement Matt Long, who leads the HMPS team. “We would have been bought by somebody else. That’s what’s happened with some of our suppliers that haven’t done this type of work; they’re getting swallowed up by stronger companies.”

Herman Miller’s Greenhouse facility in Holland, MI, offers just one example of the how far they’ve come. Designed to minimize energy use and to blend into the local terrain, the building was completed in 1995, a full decade before green buildings became de rigueur. These days it produces just 16 pounds of landfill waste per day on average; all other solid waste is recycled. With large and colorful Oaxacan animal wood carvings standing like silent sentries along its main hallway, the showcase facility houses the company’s design and engineering teams in addition to its chair assembly lines.

Aeron chair assembly line

When seating operations moved into the Greenhouse facility in 2003, the standard amount of floorspace allocated to a new chair line was 6,000 sq. ft. Today the standard allocation is 3,500 sq. ft., and it continues to shrink. Most of that space savings has gone to new models, allowing the company to introduce a steady stream of new chairs without having to invest in any new factory space. (See box, “Innovation Is Problem Solving.”) Such progress did not come from a single period of intense focus and revolutionary change. It came from a steady stream of one-second and one-inch improvements.

For example, a recent project on the Aeron chair line, which continues to yield improvement opportunities almost 15 years after the initial product launch, tackled the positioning of an automatic screwdriver. The people working on the line had to lean over excessively to pull down the driver, which created an ergonomic problem.

“It took two days to move a screwdriver two inches. I view that as a tremendous victory,” says Ken Goodson, Herman Miller’s executive vice president of operations. According to Goodson, any change that improves employee safety and customer quality—the two progress indicators he emphasizes above all others—is a victory. With no job rated higher than a five on a 10-point ergonomic difficulty scale, and with the goal always to get to zero, safety incidents at Herman Miller plants are rare today, and fairly minor.

“Anything that you do to make a job easier and less stressful for employees speeds things up,” he states. “It happens naturally. You’ve taken away inhibiting factors. The end result: More throughput.”

Recession Lessons: Losing Touches

When pushed Goodson distills the company’s entire HMPS effort down to the “simple elimination of touches.” Lean process improvement tools—5S, setup reduction, pull, one-piece flow, standard work, and so on—reduce the handling and movement of stuff. “Eliminating handling minimizes the number of people you need. Ordering one at a time simplifies the process, and you don’t handle material as much. You eliminate space in the plant, you eliminate inventory clogging your system, and you free up cash,” he says.

As the recession has intensified the need to cut costs, Herman Miller’s process improvement team has redoubled its efforts to track touches from when material enters a building to when complete orders go out on a truck. They’re figuring out how to move order consolidation further upstream from the distribution center to their factories—because lower volumes have opened up space there—and ship more product directly to customer job sites. Such changes can eliminate significant costs, even if they’re only possible in the short term.

“One of the biggest things that we learned from 2001 to 2004,” adds Brian Walker, “is that there’s a tremendous amount of cost that you can never see, and that the accountants can never find, that is tied up in the movement of goods and people. If you stay focused on eliminating wasted movement, costs drop out that you didn’t even know existed.”

Another thing that they learned during the last recession, reports Walker, is not to be afraid to experiment and take chances. A company’s lean journey can actually leap forward during slow times when lower volume reveals opportunities that are hidden when factories are running full out. It can also open up some flexibility to try new things. For example, if managers can condense weekly output that’s running on just one shift to three days, it opens up a full four days to move equipment, change workflows, and get the production line back up and running. When production is running five days a week across two or three shifts, substantial changes are much harder to manage.

Of course, to make any improvements, you have to have people who can lead the changes. Many of the manufacturing companies that have laid off employees in response to market and volume declines have reduced the size and activity of their improvement teams as well. Herman Miller managers have done whatever they can to protect such people at all levels. Continuing to invest resources in process improvement work, management’s thinking goes, will help the company get better and emerge from the downturn even stronger.

“I’ve seen something different this time,” says HMPS leader Matt Long. “In the past, we would have done across-the-board layoffs. It didn’t matter what a person’s knowledge or capability was. Now we’re three years into a very deliberate training process for our work team leaders and facilitators. By the time they’re trained we have six to twelve months invested in their learning.”

“When we’ve had to eliminate a shift,” he continues, “our general managers are making sure those work team leaders and facilitators get reassigned to a problem that they can work on and make use of their learning so we continue to make progress. We’ve stayed true to the idea that we’re going to invest in people and we will do whatever we can to protect individuals and their learning for the future.”

Having these people has allowed the company to apply more resources to problems and make faster than normal progress, according to Long. In addition, contrary to what he expected following the layoffs, a heightened sense of urgency and the desire to protect jobs has released some of the best improvement ideas that he’s ever seen.

“I’ve seen a huge pull for the HMPS team to go into areas that we haven’t looked at before,” he adds. “Even our sales group is asking us to come in and help them identify non-value-added work that they do.”

In manufacturing the HMPS team is helping area managers leverage the crisis to meet demands for dramatic space reductions. They’ve already consolidated work in the panel plant and the work surface plant where material previously moved between multiple facilities prior to completion. This has eliminated material handling equipment, work-in-process inventory, and all of the work required to organize that inventory.

“With business volume roughly half of what it was,” says Long, “We’re asking our general managers to figure out how to do the work in half the space. The goal is that when business volume comes back, we’ll be able to do the work in a much smaller footprint. It forces us to take non-value added steps and inventory out of the equation.”

To capture some of the anticipated reductions and floorspace savings that have accumulated over the past couple of years, Herman Miller announced in May that it will be moving out of its 211,000-sq.-ft. Integrated Metal Technologies (IMT) facility in Spring Lake, Mich. The closing of the IMT facility is a bittersweet indicator of the success of their lean efforts. The facility, where employees currently fabricate, paint and assemble a variety of pedestal bases, cabinets and other case goods, is where Herman Miller?s lean journey first began back in the mid-1990s.

Let the Journey Begin

A typical order for Herman Miller includes chairs, cabinets, work surfaces, cubical walls, support posts, all of which are shipped to the customer site for assembly. Everything is built to order. For a complete order to come together requires careful coordination of production activity across each of its facilities. Today the company owns and leases manufacturing and distribution facilities in Georgia, Wisconsin, and three locations in Michigan. It also has production facilities in China, Italy, and the United Kingdom. In terms of total square footage, the company occupies a third less floorspace than it did at its peak in 2002.

Visitors to these facilities will recognize many lean manufacturing approaches and tools in action:

- Yellow lines on the floor and shadow boards (5S)

- Standardized work

- Kanban cards and bins

- A supermarket in paint and metal fabricating that triggers part production based on demand in assembly

- Assembly lines that handle mixed models and colors

- ABC lanes to balance different work content between different models

- Red, yellow, and green Andon lights at each work station indicating trouble spots

- Small quantities of parts on flow-forward rack being replenished from behind by dedicated material handlers

- End-of-line billboards tracking daily output

- Hour-by-hour charts for recording actual to target output, and any issues

- Magnetic work balance boards.

- A3s to focus kaizen work and document improvements.

Work balance board and Hour-by-hour chart

Many of these pull-based, lean techniques have been used heavily in recent months as the production lines have had to adjust to falling demand. For example, team leaders and facilitators use the work balance boards (also known as yamazumi boards) to rebalance each line according to a twelve-week order demand window.

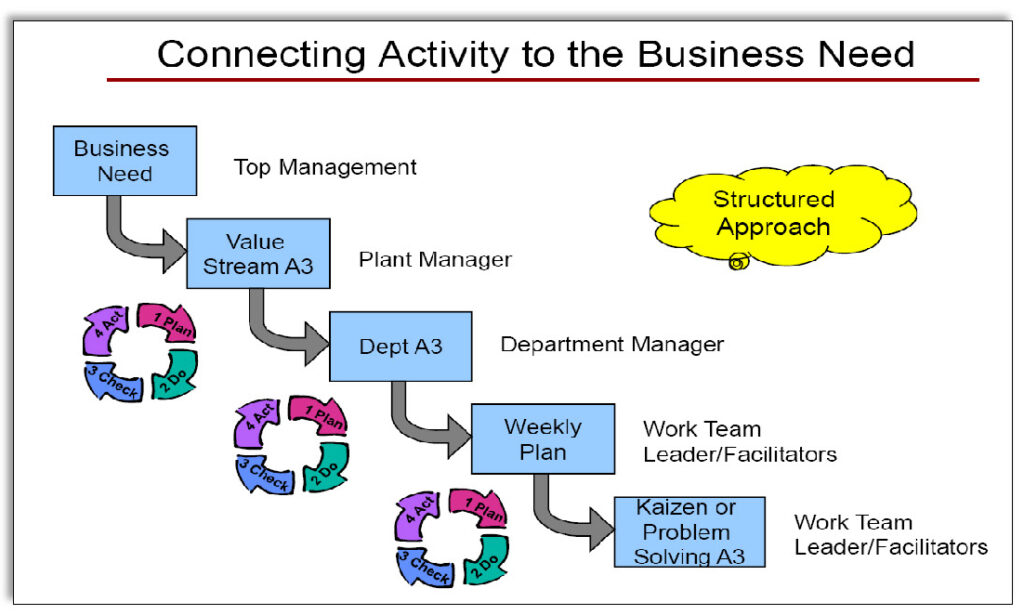

But when it comes to the success of the Herman Miller Performance System, these techniques and visual status indicators are only part of the story. (See box, “The Lean Enterprise: Long-Term Success Factors.”) A clue to what’s beneath the surface lies in the many hand-written notes and diagrams that are posted near each production area. These simple problem-solving sheets document the ongoing process improvement activity currently being carried out by line operators, facilitators, and work team leaders. Each initiative links to monthly and annual improvement plans for each production line, the facility, and the business as a whole. These plans (prepared as A3s) cascade high-level business goals down to each value stream, department, production line and shift.

The disciplined problem-solving culture wasn’t born overnight. In fact, it was a long journey that began around 15 years ago. Ken Goodson, who was in charge of the IMT facility in 1995, received approval from his boss to find out more about the Toyota Production System (TPS) and figure out how it could be applied to Herman Miller’s operations. As part of this task he made repeated requests for assistance to Toyota, which was not responsive at first. In time the company learned about a nearby automotive supplier, GHSP, that was working with the Toyota Supplier Support Center. GHSP managers offered to teach IMT about TPS in exchange for some free manpower on their kaizen team. Goodson sent two people (one of whom was Matt Long) to work full time at the facility for 6 months. When they returned to Herman Miller, the plant’s departure from batch production toward one-piece flow began in earnest.

During this period the operations team was trying to respond to capacity limitations, and was fighting never-ending quality battles. On one occasion a welding fixture was dropped and knocked out of alignment; it wasn’t discovered before an entire day’s worth of production had to be scrapped. The plant was also using trailers in the parking lot to store work-in-process inventory, where heat and condensation often caused the metal to rust. Scavenging from one order to complete another, they would sometimes repaint cabinets up to three times. When Long returned to the factory, one of the first tangible benefits of IMT?s lean program was not constructing a $6 million expansion that had already been approved by Herman Miller?s board of directors.

During one of his visits to GHSP, legendary TSSC General Manager Hajime Ohba made an unannounced visit to IMT to see the work they had started. In a very brief time he assessed the condition of the plant and gave them some “homework” and some very lofty goals. IMT leaders started to work right away and during a follow up visit Mr. Ohba was impressed enough with their diligence that he agreed to work with the plant. He sent his people to the facility every other week for three years, and later to conduct Friday progress reviews. At the time the pedestal line, where employees assemble metal cabinets, included two production lines with four cells and 126 people working across three shifts. After walking the line, Mr. Ohba said they could achieve the current output with one line, two shifts and 16 people. After 10 years the line hasn’t quite achieved Mr. Ohba’s ultimate productivity vision, but it’s very, very close.

One of the challenges that managers encountered was transitioning away from a craftsman mentality for orders of 1 or 2 pieces. In some cases people used to build an entire product, putting their heart and soul in it. Moving to pull and flow, building small orders on the main production line, required a huge shift in mindset. Managers spent a lot of time on education to overcome the belief that the changes being implemented would hurt rather than help customer quality.

“After three years with TSSC, we had learned to build a working system and they told us it was time to stand on our own and spread our learning to other areas,” recalls Long. “They continued to push us to make the pedestal line a Toyota showcase line, a value stream that demonstrates an effective working model of TPS. Like a “mini automotive plant,” you can stand in one spot and see the whole system. “Never in that time, I don’t think, did anyone ever answer a direct question with a direct answer. They always asked questions back, forcing us to come up with solutions on our own.”

In 2000 Goodson became executive vice president for Herman Miller’s North American operations. He was charged with rolling out HMPS in a systematic way across the corporation. With a long history of independent leadership, up until this point the general managers of each of the company’s then 13 facilities had been following their own unique production and improvement program.

“Lean practices are hard to install, hard to get people to understand, and they’re counterintuitive,” says Goodson. “It requires cultural change whether you’re rolling it out in one building, multiple buildings in a region, or worldwide. I don’t think there’s any area, any department or any building where it’s been easy. People don’t realize how hard it is. It’s not a fad diet. It’s a lifestyle change.”

“Over time it doesn’t get any easier. I don’t want to say it gets harder because one thing that has gotten easier is that people understand the value. They know this isn’t a flavor of the month,” he adds.

When asked why Herman Miller has been successful at rolling out lean manufacturing across the company when similar efforts at so many other companies have failed or lost momentum, Goodson cites unwavering leadership support and a singular focus. “Our general managers understand that they need to apply these techniques in the way we want them applied. I’m not interested in bringing other programs in. I’m not interested in anything else. Our managers are not permitted to pursue anything else or modify the HMPS program. Period.” He states.

Such focus is aided by a dedicated continuous improvement team that works with the general managers and department leaders to develop their A3 improvement plans and help them make progress toward their goals (See box, “Time for Reflection.”) The HMPS team consists of 18 people. At any given time half of them are working in manufacturing and the other half are working in other areas, including the business side, the distribution network, with suppliers, and with dealers. Turnover on this team of process improvement advisors is intentionally high because their members regularly get recruited to spread learning throughout the organization.

It should be noted that the HMPS team does not oversee specific projects. Their role is to support what each of the business leaders wants to achieve. The business leaders are responsible for hitting certain improvement targets. The HMPS team helps them lay out an improvement plan that will achieve those targets. They provide coaching and conduct weekly, monthly and quarterly progress audits. There’s a strong emphasis on taking risks and learning, even if the results sometimes fall short of the mark.

“If Matt likes what’s going on, that progress is being made and that the effort is there, I’m happy,” says Goodson. “If he’s not happy, then I get involved, and people don’t like that.”

During the corporate-wide lean rollout, every plant had to get approval for new expenditures from the HMPS team before it could spend any money. The point of this hurdle was to make sure that the root causes of any issues had been identified, and simple solutions exhausted, before any money was thrown at a problem. Because of the radical changes required in a short period of time following the dot-com industry implosion, many process and workflow changes were instituted in a top-down fashion. This approach ran contrary to Herman Miller’s collaborative culture. Once the immediate crisis had passed, however, they went back and conducted follow-up training and coaching to reinforce what had been done.

“Going into this recession, I have hundreds of people out there who are experienced in these techniques,” says Goodson. “It’s a totally different experience now. We know what we’re doing, and how to get to the other side.”

People: Key to Sustainability

Herman Miller has been recognized by FORTUNE magazine as one of the “100 Best Companies to Work For,” and is a perennial member of the publication’s “Most Admired” companies list. It has also been recognized by the Great Place to Work Institute, by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, and by IndustryWeek magazine as one of the 50 Best U.S. Manufacturing Companies. (For data on how the lean transformation has affected corporate performance, see the series of charts By the Numbers: Herman Miller’s 10-year Lean Journey.)

While such awards are always nice, of much more importance is the underlying cultural advantage that they reveal. After an initial tool-focused phase, Herman Miller’s long history of employee participation and ownership provided fertile ground for the adoption of the people-centric and continuous learning aspects of TPS.

“An organization shouldn’t ever be only as smart as the leader. It should be as smart as the collaborative whole,” says Goodson. “Our people have the right and the obligation to talk to us. They ask managers questions and demand answers. And we have the obligation to get them answers.”

Each work team leader and facilitator at Herman Miller goes through a six-month HMPS training program that is designed to reinforce their inclination to ask such questions, and give them the knowledge to improve their work areas. The training, which varies in length depending upon the individual, is more of an on-the-job internship than a classroom-based program. In addition to the lean toolkit, the intent is to instill a thorough understanding of the scientific method and encourage experimentation. Core skills include basic machining knowledge so they can mock-up fixtures and test setup changes on their own without relying on engineering or maintenance.

“We can only go as fast as we can develop leaders,” says Matt Long. When the company first started implementing lean in the mid 1990s, and again when HMPS was rolled out across the company, the adoption of lean tools outpaced people’s lean knowledge. When that happens everyone’s first inclination when a problem pops up is to revert back to the old way of doing things.

“The tools and people’s capabilities in terms of thinking and doing must be in balance. As tool adoption advances, people’s capabilities must also advance,” says Long. To formalize this knowledge advancement process, each area has a human development plan (again, written in pencil on one piece of paper) that connects the desired behavior and learning needs to the business needs. It includes a summary of the target condition, and a detailed implementation plan for getting there.

Human Development Plan

One of the defining characteristics of an organization that values experimentation is that it continues to learn and adopt new ideas. Last fall Herman Miller rolled out the job instruction aspect of Training Within Industry (TWI), a World War II-era approach to rapid skill development. They are using it to teach work team leaders and facilitators how to be better trainers. To help minimize the production impact of the staff reductions, the company’s general managers decided to speed up job instruction implementation.

“In January we literally had some lines with all new people who had never run that product before,” says Long. “In the past if we had switched out so many employees on a line, our ability to hit takt time would have dropped 20 to 30 points. Today we’re seeing a minimal drop in operational availability for the lines employing job instruction.”

The job instruction method is even improving productivity in established areas, according to Long. For example, one operator who has worked on the Aeron chair line since it started was achieving five to six seconds of variability at one work station, which meant that he was sometimes stopping the line. Following job instruction training, he now understands the nuances of the work requirements, allowing him to do it within takt time every time.

“You take a job and break it down into the key steps, the key points for those steps and the reasons behind those key points,” Long explains. “People might have seen their peers doing a job differently, but no one ever measured who got the best results or the best quality. With job instruction a facilitator or work team leader studies the people doing the job, identifies the best combinations, and documents the key points and reasons for those key points. Then, through repetition and coaching, they work with everyone to do the job exactly the same way.”

Kaizen Every Day

“Everyone looks for home runs. In the beginning those are everywhere,” says Pete Pallas, director of operations for the IMT plant. “They’re not there anymore. Today three or four seconds is a big gain.”

Still, those two-inch and one-second changes add up. On one chair line, for example, Herman Miller employees completed over one thousand “kaizens” in one year. The average impact was 0.5 seconds, which might not seem like much, but the cumulative result was a 60% increase in capacity, and annual savings of more than $1 million.

Such results are what day-to-day kaizen is all about. On some occasions, when urgent changes are required, Herman Miller managers will pull together a team for a focused project, working over a week or two to analyze the problem, design a solution and implement the changes. But that’s the exception rather than the rule.

“If we look back 14 years, the difference is amazing. But when it was happening you really couldn’t see it,” says Brian Walker. “I remember having conversations with our board in the early days. They wanted to know the end result. We couldn’t describe it to them. We thought it was going to be big, but we didn’t have a way of saying how big we thought it would be.

“We had a watershed moment during our last economic downturn from 2001 to 2004,” Walker recalls. “We took the board of directors into a building that we had just built four years previously. We walked in and it was completely empty. We’d emptied an entire building and had not reduced capacity. They got it then.”

Beyond the four walls of their facilities—what Herman Miller managers refer to as the “first mile” (supply base) and the “last mile” (dealers and distributors)—the company’s lean efforts have proceeded in fits and starts. According to Long, they’re still smarting today from initial supplier development efforts back in 2000 that took a “swat team” approach. Herman Miller’s lean experts would dive in, help their suppliers make process improvements and cut production costs, go home, and then demand price reductions.

Today, with most primary suppliers within a 30-mile radius of its Michigan factories, they have five full-time HMPS people who train Supply Managers to work collaboratively with their suppliers. Expectations for annual price reductions haven’t changed, but they do look at the numbers to make sure their 33 partner suppliers (which represent 70% of total spending) are making sustainable margins. “They now say we’re doing lean with them, not to them.”

The HMPS team tackled the company’s distribution network during the last downturn. Previously, they pushed product out of the factories to seven distribution centers where it had to be sorted by customer order. In 2003 the company reduced its storage footprint to two distribution centers that pull sequenced product based on customer orders. Ultimately, they decreased warehouse inventory from 4.5 days to 1.5 days, and reduced annual distribution costs (not including transportation) by $5 million. Gross sales handled by one of the two remaining distribution centers have increased from $9.7 million per week in 2001 to over $15 million per week today.

“As part of that change, the manufacturing general managers and their people came to the distribution center to unload trucks from their factories,” recalls Long. “That helped them to see the internal customer experience and how it could be changed to reduce extra handling.”

Whenever possible Herman Miller now ships directly to the customer job site, bypassing both the Herman Miller distribution center and dealers’ warehouses. It took time to build up enough trust with dealers that they could consistently deliver complete orders to the customer site. The HMPS team has also worked directly with furniture dealers to implement lean processes. These efforts didn’t really take hold until they moved away from working on business areas—optimizing the dealer invoicing process for example—and focused on furniture installation and setup, something end customers really care about.

In product development, Brian Walker reports, they are working hard today to use the capacity that’s been freed up to accelerate the new product launch cycle. The strategy is somewhat counterintuitive in a downturn, but the objective is to have more new products on the market than the competition when things start to turn around. In addition to furniture, seating and cubicles, this includes a unique plug and play power and communications network system that dramatically reduces the labor required to setup and reconfigure an office space. Again, not having to add any new buildings has freed up resources to invest in what dealers and customers really want, which is the latest and greatest products.

“All of the work that we’ve done leading up to this point sets us up to weather these market challenges much better than a company not using these techniques,” concludes Goodson. The magnitude of the IMT plant closing is just one indicator that dramatic improvements are still possible after so many years. He continues, “What are we going to do two years from now? I don?t know. It’s going to be better. I just don’t know what it’s going to be, which is kind of cool.”

By Definition, Innovation Is Problem Solving

Herman Miller’s long history of product innovation complements its embrace of process innovation.

The original company that eventually became Herman Miller started in 1905 as Star Furniture, a manufacturer of traditional residential furniture. D.J. Depree purchased the company in 1923 and named it Herman Miller after his father-in-law who had loaned him the money to buy it. The company evolved into a leader in “modern” furniture in the 1930s and 1940s, and developed successful partnerships through the 1950s with legendary industrial designers, including Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, George Nelson, and Isamu Noguchi. In the 1960s, Robert Propst developed the world’s first open-plan office furniture system, affectionately known today as “cubicles.” Herman Miller introduced the concept of ergonomic office seating in the 1970s, and in 1994 the company introduced the widely lauded Aeron chair, which is included in the industrial design collections of museums worldwide.

Competing globally from its headquarters in Zeeland, Michigan—on the opposite side of the state from Detroit—today Herman Miller is the second largest manufacturer of office furniture in the world. Net sales grew from $262,000 in 1923 to $25 million in 1970, the year the company went public. Sales of Herman Miller office systems, seating, furniture, and other products exceeded $1.6 billion for its fiscal year ending May 31, 2009. Furniture sales come mostly through independent dealers. Following the fortunes of the commercial construction industry, analysts are projecting continuing market challenges through the second half of 2009.

Regardless of market ups and downs, Herman Miller’s innovation strategy requires constant investment. Design and research spending, including royalty payments to designers, totaled $51.2 million, or 2.5% of sales in 2008. In addition to constant new product introductions, such investments have contributed to a spate of technological innovations. The Patent Board ranks Herman Miller among the top 50 companies in the consumer products sector based on patent-based intellectual property.

Developing aesthetically and functionally innovative new products requires a doing more-within-limits mindset that long-time lean manufacturing practitioners would appreciate. Charles Eames himself defined design as “a plan for arranging elements in such a way as to best accomplish a particular purpose.” He noted that one of the keys to the design problem is “the ability of the designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible—his willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints—the constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time, etcetera.” *

Such an approach continues to this day, according to President and CEO, Brian Walker. “If designers see lean as a constraint, something they have to think through, it can make them better. A constraint may be the desired number of parts, or ease of assembly,” says Walker. “Lean ties very much into Herman Miller’s long-standing belief in innovation. We really believe that our innovations come from problem solving.”

“We have a new chair coming out this summer, called Setu, which is a great example of taking a complex product and tearing it down to its basics in terms of parts and the assembly process,” Walker explains further. “Our designers worked very hard to make sure the base of the chair and understructure didn’t need coloring because they know that having to sequence colors on the production line is very complex for the folks in manufacturing. Their challenge was to not use color and do such a good job with the design and material choice that you’d never want color because it is so beautiful without it. To me that’s lean thinking infused in design that actually made the design better.”

* Eames Design: The Work of the Office of Charles and Ray Eames, By John Neuhart and Marilyn Neuhart, quoting a documentary film about the Eames’ work (Harry N. Abrams, 1989).

The Lean Enterprise: Long-Term Success FactorsAs many companies have discovered, it can be exceedingly difficult to sustain a lean program and continue to deliver dramatic results beyond three to five years, after which performance improvement frequently plateaus. Here are some of the critical factors that have helped Herman Miller maintain its momentum over the years.

Create a crisis. “We have a natural crisis today, but that isn’t accelerating our work. It did during the last recession. What I’ve done over the years is set real stretch goals. One year it was reduce cost of goods sold by 25%. That forced everyone to work together—manufacturing and purchasing, purchasing and marketing, manufacturing and sales. We didn’t hit 25%, but we did get a 12% reduction in our cost basis, which was very good.”

Invest early in developing lean leaders. “Early on, TSSC developed our internal Lean leaders through one-on-one coaching at IMT. We even sent three leaders to work as interns at TSSC for a year or more. These people remain at the core of our HMPS team. It’s important to have a strategy to build your own capability internally rather than relying on outside consultants for the long term.”

Create a model line. “TSSC coached us to carefully choose a key value stream (we chose pedestals) then build a working example of TPS before trying to spread it to other areas. This ‘narrow and deep’ model line approach allowed us to work out the nuances of the system for our industry and provide a compelling story to our leaders. We have followed the same approach in every new area that we go into.”

Focus on learning and behavior, not just physical changes. “If the team is not engaged and part of the learning, any physical changes will quickly revert to the old way. We’ve had to become students of change management and people development.”

Stay on task. “Lean people are teachers. You have to keep them on task. If you allow teachers too much leeway to explore ‘teaching moments,’ managers will get frustrated because they aren’t learning how to solve their immediate problem.”

Keep making improvements when times are good. “We’ll take a look at an area, one of our chair lines for instance, and decide that we need to make it a little longer or a little shorter. It’s already pretty efficient, and yet we’re attacking it and trying to make it better when times are good. That’s tough because things are going well, and people question why we’re doing it. During tough times, like now, no one’s questioning anything.”

Long-term management tenure. “We have people who are well-versed in the industry and the company, and they’re not here for short-term results or short-term gratification. These are all people who see themselves as owners of the business. Not just in financial terms, but they own it emotionally. We see ourselves as being stewards of the company and stewards of our employees. Having a longer-term point of view allows you to make changes incrementally, period by period. You can see them happening, because you’ve been around long enough to remember what it used to be like.”

“The fact that key company leaders Brian Walker and Ken Goodson have been in their roles since the inception of HMPS has been key. They have been constant champions with an unwavering commitment and vision. When we?ve had plant management turnover, and another manager without HMPS thinking has stepped in, we have lost considerable ground and had to rebuild. We have since learned that we really have to groom and train replacements ahead of time.”

It’s hard. Get over it. “People don’t realize how hard this is. It’s not a fad diet. It’s a lifestyle change. We have evolved to that over time. But we didn’t think of it that way initially.”

Time for Reflection

One word that continually pops up in conversation with Herman Miller operations managers is “reflection.” The word reveals a tendency, which arose in part from their interaction with the Toyota Supplier Support Center, to take the time to assess what they’ve learned. It also refers to daily, weekly, monthly and quarterly status reviews.

Work team leaders and facilitators huddle after each shift to reflect on the day’s problems and review progress on any kaizen activities. They also have weekly reflections with their managers to gauge progress on their A3s, reviewing any experiments that worked and those that didn’t work out as expected. Every month general managers do a facility walk through with representatives from the HMPS continuous improvement team. Again, these meetings are meant to track progress and individual learning against expectations.

“It started out as something the HMPS team was leading,” says Matt Long, Director of Continuous Improvement. “But our goal was that the GMs and managers would lead the monthly reflections, and that’s how it’s working now. They used to hate it, and we had to force them to go through it because our vice president said they had to do it.”

The company’s general managers didn’t like the monthly reflections for a variety of reasons. First, they felt that they already had to meet daily output and quality targets, and this was just an extra thing that they had to do. Second, Long’s continuous improvement team habitually uses the Socratic Method, which means that they tend to answer questions with questions to help managers develop their own thinking. Such responses can be frustrating when someone just wants to hurry up and get an answer. Managers were also unfamiliar with the visual format of the A3 form.

“Now they recognize that it’s not enough to just get product out the door,” says Long. “They need to show their managers how they are improving their areas every month. I think the expectation for improvement has become embedded, and they understand that the best way to make improvement is to continually be reviewing the plan, figuring out if they’re going in right direction, making progress, and adjusting the plan as they go.”

When Herman Miller first introduced the review process they scored managers based on their performance, and linked a portion of their pay to the score. “As we learned, that’s not an effective way to motivate people,” Long continues. “Production managers are masters at hitting a number. They would end up putting on a show to try to get a good score, and do most of their work a few days before the walk through. That wasn’t the behavior we wanted.”

Today, Herman Miller uses a red, yellow, green scoring approach. Green indicates that a manager has a good improvement plan and the HMPS team sees good thinking and incremental progress toward the goal, even if the manager has tried some things that haven’t worked out. Yellow indicates that they have a plan but they’re not making any progress. And red, they have no plan. If a manager receives a red or yellow score two months in a row, they get an immediate call from the executive vice president of operations for an explanation why they aren’t making any progress.

Investing in Work(ers) Using Job Methods and Job Instruction

Learn how to develop team members for sustained success.