It may seem surprising that about 60 years since Toyota and a few other companies first introduced hoshin kanri there is still a need to write about what may seem to be its basics. Those of us who see the Toyota Production System, or “lean,” as a highly effective and beautiful sociotechnical system have for decades been telling anyone who would listen “it is not about the tools.” And here we have a foundational tool, or process, that can help align everyone in your organization, vertically and horizontally, toward common business objectives. But that is if, and only if, it is viewed as part of a sociotechnical system, and not simply a technical tool. Or we might say, it is a socio-technical tool or process.

This is now brilliantly explained in great detail with a fictional but realistic case study by Mark Reich in his new book Managing On Purpose. What we can learn from Mark’s book is not just the abstract concept that hoshin kanri is more than a technical tool, but we can see the sociotechnical system come to life through the detailed example.

Imagine

If each of your 10 or 10,000 or 100,000 team members were fully aligned. They knew deeply and were fully committed to the organization’s purpose and the vision to realize it. They knew the purpose of their own work and what their individual contributions meant to the broader vision. They had a laser-focused view of their purpose and goals and how achieving their goals helped others achieve theirs. They actively participated in the planning process, collaborating and learning together with leaders, peers, team members—leading to shared commitment and knowledge.

Of course, plans are simply plans. The real learning happens when plans meet reality. What if the learnings of each team member as they face obstacles, both predicted and unforeseen, are also shared, enabling collective adaptive responses to changing conditions?

Would all of this be a certain kind of organizational nirvana? An ideal? A target condition? A True North?

Striving for such a condition is the aim of the process variously known as hoshin kanri, strategy management, or more often (and misleadingly) policy deployment, or perhaps most accurately, “navigating organizational direction”: a vision ties together an organization’s broad purpose, its strategy, and its goals and targets to daily execution. Yet even the best practitioners of this approach realize this perfect condition will never be reached, but they also understand that hoshin kanri keeps them moving ever closer toward the desired state.

Hoshin kanri:

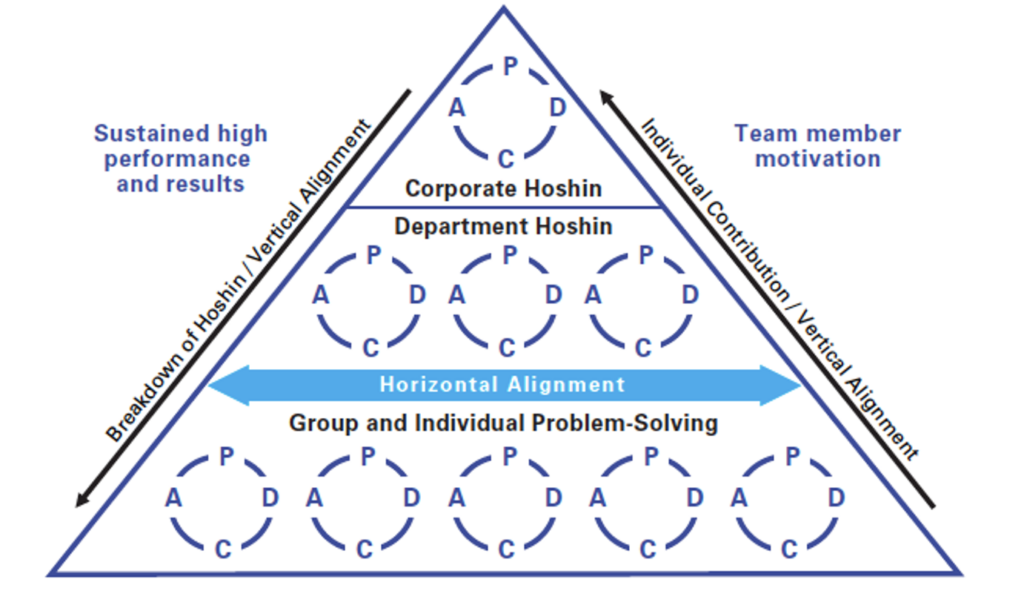

- Is dynamic wayfinding based on situational awareness;

- Aligns activities across levels in pursuit of a challenge; and

- Embodies PDCA (plan, do, check, act), both long-cycle and short-cycle. The hoshin kanri process supports long-cycle PDCA (occurring over months and years), where many organizations struggle and where big gains are possible. Short-cycle PDCA (as with daily management or cycle-to-cycle work) is more intuitive, often focused on managing deviations or implementing clearly recognizable improvements, but even short-cycle PDCA takes strong problem-solving skills and benefits from a clear way of prioritizing what to work on.

Hoshin kanri is a collaborative deliberation and decision process as well as a dynamic execution and learning process. It keeps organizations and individuals aligned to their purpose. Hoshin kanri, when practiced consistent with the philosophy of Total Quality Management, is a process that is equally top-down and bottom-up.

Hoshin Kanri at Toyota

Toyota is one exemplary practitioner of the hoshin kanri process, with a full 60 years of experience. Hoshin kanri grew out of the Total Quality movement in the early 1960s, with much of the technical detail developed by Japanese quality experts based on the experience of Bridgestone Tire Co. Hoshin kanri has been quite widely adopted in Japan, but spottily adopted elsewhere.

At Toyota, by the early 1960s, Eiji and Shoichiro Toyoda saw the need for the company to strengthen its management systems and the managers who led and worked within them. The Toyodas directed company executive Masao Nemoto (who provides his first-hand account of the company’s introduction to Total Quality in The Birth of Lean[1]) to lead the company’s adoption of hoshin kanri to fill a critical need as the enterprise grew. Those leaders knew that Toyota needed to compete globally and, therefore, needed to develop itself into a door-to-door excellent enterprise. Quality at the time was below average. They recognized that the heroic efforts of a relatively small number of exemplary leaders had helped the company achieve its success to date, but that their grand dreams required all leaders to collaborate and contribute in a big way.

In those days, while they competed fiercely with each other, Japanese corporations were extraordinarily collaborative. The post-WWII demands to rebuild the country led to a collective effort of the entire nation. Inter- and intra-sector competitors shared quite openly. Bridgestone is often cited as the first to formally adopt the term “hoshin kanri” and in 1965 published the results of a study they had conducted about the hoshin kanri activities of various companies.

It was in 1963 that the Toyodas challenged Nemoto and team to look at how to apply TQC/M (Total Quality Control/Management) across the enterprise. Nemoto, accepting the challenge, put together a team, began the process of learning, and instituted TQC throughout Toyota. Mikio Sugiura depicts the process in his book (Japanese only, though John is working on a translation) Toyota ‘Global 10.’[2] He tells how Toyota put its hoshin to paper for the first time in January 1963 and socialized the thinking and gained alignment among all employees. It consisted of three parts: basic hoshin, long-term hoshin, and annual hoshin. The basic hoshin was:

- Leverage the full potential of each person of the extended enterprise to develop into a “Global Toyota.”

- Enhance our reputation as the “Toyota of Quality,” thoroughly committed to “Good Thinking, Good Products.”

- Contribute to national economic development through establishing a production system that provides high volume and low prices.

Sugiura goes on to describe company hoshin and the annual hoshin kanri process as extensions of the “kanri cycle” of PDCA. Just as PDCA evolved in Japan—building on ideas taught by Dr. W. Edwards Deming—hoshin kanri emerged as a Japanese innovation based on American inputs from Homer Sarasohn, Charles Protzman, Deming (and, vicariously, Walter Shewhart), Joseph Juran, and Peter Drucker. The ideas of these Americans were combined with the strong sense of need and local ingenuity among Japanese protagonists, led by Kaoru Ishikawa and his team at the University of Tokyo and industrialists, including leaders at Bridgestone, Matsushita, Toyota, and others. One could say that hoshin kanri as it developed during this period was essentially the structured application of PDCA to the macro level of an enterprise.

There are now a variety of sources to learn about hoshin kanri, going back to Joji Akao, Tom Jackson, Pascal Dennis, Mark Reich, and others. Many people we know seem to come away from reading about or attending a seminar about hoshin kanri thinking that it is equivalent to senior leaders filling out a form like an X-matrix or identifying objectives. If only it were so simple. “Jumping to the tool” causes its own set of challenges, especially when the tool is applied at the enterprise level.

Hoshin kanri is a process of not just filling out forms, but collaborative planning at all levels to align visions and goals. What all too often is missing when we focus primarily on outcomes and high-level activities is critical information about how and who. How will the organization go about executing as it learns dynamically along the way? Who will the organization involve to get alignment both horizontally and vertically in each key initiative. The processes of getting the information and developing the plans, the communication within and across departments, executing collaboratively via a robust process of PDCA, and the coaching to develop problem-solving capability are the real essence of hoshin kanri.

While hoshin kanri is powerful in its own right, it is best seen in the context of a complete enterprise management system that includes daily management—managing the day-to-day work of running the business—and mid-level management processes to facilitate smooth end-to-end value-creation on behalf of customers. The real power comes when managers at each level take responsibility, acting as entrepreneurial owners of problems and challenges while at the same time developing the capability of team members. We often speak of ownership. In this context, ownership means I want to know what others need from me so I can figure out what I must do to help them succeed. My failure can lead to their failure. Ownership is self-commitment to successfully fulfill one’s role.

The process of developing the plan and checking it later (months later in the case of an annual hoshin kanri process) takes one of the most taxing and difficult cognitive skills. In Daniel Kahneman’s words, it takes slow thinking. In this case slow thinking is what Toyota calls problem-solving. In Toyota diagrams about hoshin kanri they say it depends for its success on two human processes: problem-solving and on-the-job development (OJD). OJD is the daily coaching process of developing your people to solve problems at the root cause. Even in the planning stage of hoshin kanri it is not sufficient to deploy targets and get everyone to agree.

When your boss shares the goals they have agreed to with you they are asking what you will work on to help them achieve these goals. You might submit a proposal A3 that clarifies what they are asking for, summarizes the current state, and identifies key process variables that you believe are drivers of the outcomes they want (in fact, you might have already submitted that proposal, the means by which each individual contributes to not only execution but development of the hoshin). In other words, they want you to go the gemba to study the current process and work to understand causality or what Toyota calls root causes. Causal reasoning is much more difficult than simply taking the outcome goals of your boss and calculating out your contribution.

At Toyota, your boss is almost surely more experienced and skilled in problem-solving than you, and their job is not just to sign you up to goals but to engage you to take ownership of the output of your own work, to solve problems and do kaizen to continually improve performance, and to coach you to further develop your skills, just as their boss is coaching them. At Toyota every leader is a coach and a learner. Thus, we can say that hoshin kanri is not only a process to get results, but an opportunity—even a necessity—to develop people.

So What?

You are not Toyota. You are probably not a Japanese company, and you may very well not be a manufacturer of any sort. You may be in an organization that looks seemingly nothing like the pyramid illustrated above. Still, we are convinced that you can benefit from embracing the intent and process of hoshin kanri. How so?

There is a gap between what is often taught as the application of hoshin kanri as a technical tool and the practice as exemplified by companies like Toyota that successfully apply it as a socio-technical process. The critical question, then, is how can we close that gap? It clearly takes more than a high-level description of the process.

Years of learning from Toyota and many other companies has taught us that copying best practices is rarely successful and that certainly applies to hoshin kanri. Many if not most efforts are superficial, resulting in a process that is little more than rebranded management by objectives (MBO), perhaps labeled objectives and key results (OKR), with a top-down cascade of KPIs. The mindset and fundamental shift in management practices remain elusive for most. We figure those shifts, especially the mindset (and associated culture), will take time to reach a tipping point for organizations in general. But, where there is a will, we have seen that a best practice enabling structure can help.

True of any best practice but especially an enterprise-wide one, hoshin kanri needs to be adopted and evolved as part of the culture and very fabric of each organization. Every organization has its own aims—and its own problems. Hoshin kanri, just like its more famous sister TPS, takes root when adopted wholeheartedly, systematically, and situationally. From a lean thinking perspective, it starts with gaining clarity, from top to bottom, on value-driven purpose and developing the capabilities to address the problems, obstacles and challenges to achieve it.

As illustrated even in Mark Reich’s book, a success story, the road to adoption is rocky as the enterprise works to adopt this new and very different way of thinking, collaborating, and planning. If you are already using hoshin kanri, then think about whether you are using it as a purely technical tool or as a social and technical one. If you are new to hoshin kanri, perhaps try it on a pilot basis for a part of your organization. Whatever you do, however ambitious, it can only help you deliberately determine and remain focused on your purpose, set goals accordingly, and make and execute plans to achieve them as you learn your way forward. There is no pass-fail, only learning. Toyota would not be the company it is without hoshin kanri. We believe it can have a profound effect on any organization.

[1] Koichi Shimokawa (editor) and Takahiro Fujimoto (editor), The Birth of Lean (Brookline, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute, 2009).

[2] Masaki Shibaura (aka Mikio Sugiura), Toyota’s ‘Global Ten’—From Mikawa to the World (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2017).

Welcome to The Management Brief — a weekly newsletter from the Lean Enterprise Institute delivering actionable insights, strategies, and stories on lean management. Each issue explores proven methods like hoshin kanri for strategic alignment, A3 problem-solving, and daily management that foster stability, improvement, and innovation. We aim to help you build resilient, high-performing organizations prepared for long-term success. Subscribe for free and join a community dedicated to management excellence.

What a great article. Even though I have been a student and practitioner of total quality management for over 30 years and lean management (TPS) since 2009, I learned how they fit together. Also, the history was fascinating on how Hoshin Kanri started and evolved. The best article I have read on this subject.