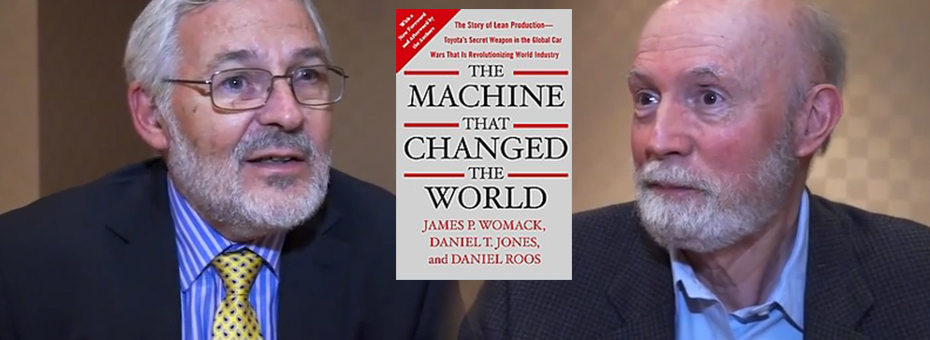

Toyota today stands as the most powerful example of lean as a complete business system, fueling sustained growth and success. Back in 1990, authors Jim Womack, Dan Jones, and Dan Roos published their groundbreaking book, The Machine that Changed the World. It was the first popular book to identify and promote Toyota’s famed production system, and played a vital role in launching the entire Lean movement. In this article, prepared for the revised book in 2007, Jim Womack correctly forecast Toyota’s rise, and identifed the vital elements of a complete lean production system. He also spoke of then-current debate over whether Toyota would pass GM and Ford as the world’s largest automaker. It eventually did, and the subsequent impact of this “crisis” (the lean model prevailing over mass production) continues to reverberate today. His piece lays out this revolutionary system, which is still early in adoption and ripe for continued improvement.

Recently, as I’ve listened to industry executives and the media grapple with this momentous event [Toyota passing GM and Ford], I’ve been struck by the manifest irrelevance of most efforts to find the root cause. The crisis is not due to misaligned currencies, subsidies from “Japan, Inc.”, or spiking energy prices (although the latter has affected the precise timing). And it is not a simple case of too many retirees for the present workforce at GM and Ford to support. (Indeed, this gets cause and effect backwards: GM and Ford have too many North American retirees for current workers to support because both companies have lost half of their North American market share over the past 25 years and have hired hardly any new workers in a quarter century.) The root cause of the crisis lies in a clash of two business systems, and the better system is winning.

As we pointed out in Machine – devoting a chapter to each point – a lean enterprise consists of five elements: a product development process, a supplier management process, a customer management process, an overarching enterprise management process, and a production process from order to fulfillment. And each of these processes is superior to the processes employed for the same tasks at a mass producer.

The lean product development process, as used at Toyota, permits a company to produce vehicles with fewer hours of engineering and fewer months of development time with fewer defects while investing less capital and making customers happier. The key tools are the chief engineer concept, concurrent set-based design (which is simultaneous as well), and high speed prototyping with trade off curves so that re-invention is avoided. (It’s not an accident that Toyota was able to hear the voice of the customer first with regard to hybrids or that the Prius – with more new technology than any vehicle in a generation – was developed very quickly and was recently reported by Consumer Reports to be the most reliable vehicle sold in the U.S. These were predictable outcomes of the lean development process.)

Lean supplier management creates a small number of highly capable suppliers in long-term partnership with their customers. Suppliers work to demanding customer targets for cost, quality, delivery reliability, and new technology and achieve these targets by jointly examining the development and production process they share with their customers. The lean approach has dramatic and predictable benefits, but if GM and Ford even understand these concepts, their perceived need to save themselves by bleeding their suppliers has made implementation impossible.

This practice of asking the correct questions rather than providing the correct answers is perhaps the starkest contrast between lean thinking and orthodox mass production and the hardest to implement.

A lean customer management system builds customers for life while reducing distribution costs by working backwards from the customer’s desired experience and forwards from the production system’s needs. In fact, although Toyota has deployed these concepts brilliantly in Japan, it has stumbled so far in applying them in the U.S. Its Lexus dealing system has created a very high level of customer satisfaction but at substantial cost. Achieving high satisfaction and low cost is a key topic in my and Dan Jones’s recently released Lean Solutions book and provides a terrific opportunity for GM and Ford to move ahead of Toyota by using its own methods. Or, if they fail, this could be the final act in the tragedy as Toyota finally makes its retailers lean in the next few years, the way it transformed its service parts operations in the 1990s.

Finally, a lean management system involves managers at every level posing the key problems that need to be solved and asking the teams they lead to develop and implement the answers. This practice of asking the correct questions rather than providing the correct answers (which high-level bosses can never know in any case) is perhaps the starkest contrast between lean thinking and orthodox mass production and the hardest to implement.

Putting these four elements together, it’s not surprising that lean exemplar Toyota is steadily advancing, as recovering mass-producers GM and Ford steadily retreat despite adopting parts of the lean system. And note that I have not even mentioned the fifth element of a lean enterprise – production operations – because GM and Ford are now nearly competitive on this dimension in terms of labor productivity. The root cause of the current crisis is not in the factory. It is in the rest of the value creation system.

Managing a Lean Enterprise

Learn how to drive performance and inspire innovation using hoshin kanri, daily management, and A3 process.