When Halfway Toyota acquired Ngami in 2013, our people were scared and angry: the same owners had run the car dealership, and suddenly massive change was on the horizon.

I had seen takeovers before, and I had seen people fighting against them and wanting to just hang on to their old ways. And it never worked. Halfway wanted us to introduce lean thinking, and I was determined we’d give our very best to try and change.

At first, there was mistrust and militancy: people felt let down and didn’t understand the new system we were trying to introduce. The context around us certainly didn’t help. Life in Botswana is hard: many people in our district live in poverty; those who don’t (because they work) care for up to eight family members—an important role in Batswana society and a part of our culture of respect. People often live in one-room houses without power or water. Many of them have sick family members to look after (our country is experiencing one of the most severe HIV/Aids epidemics in the world, with the third-highest HIV prevalence rate among adults in the world).

The odds seemed to be stacked against us, and it took a lot of work, pain, and tears to overcome the obstacles we were facing. Yet, it was by acknowledging that life is hard that we found the key to our transformation.

Overcoming Resistance

When Terry O’Donoghue, Halfway’s COO and former Toyota South Africa vice-president, and Dave Brunt, Lean Enterprise Academy’s CEO, first came to Maun to help us initiate the dealership’s transformation, Ngami was very hard to control. I often compare it to a dragon, which generated a lot of gold but didn’t release it willingly. The previous management was convinced that the only way to tame the beast was being assertive and saying “No.”

We decided to try a different approach, one that recognized the difficulty people were experiencing at work and home—an approach that would make their job easier to understand and carry out. Work doesn’t have to be complicated. We want our people to be able to do it on bad days just as easily as on good ones, even when the retroviral drugs they are on are taking their toll or when they have been up all night looking after a sick family member. They need their job, and they need to do it right no matter how they are feeling.

The real transformation at Ngami started when we began to respect that our people were struggling.

The real transformation at Ngami started when we began to respect that our people were struggling. Why would we want to make anybody’s work and life harder than they already are?

Desperate to get our people on board, we decided to have individual conversations with each one of them; they are valuable to us as 86 individuals, after all, not as one “workforce.” We found that their complaints, too, were individual. It took weeks to explain to them what we wanted to do, but listening to their worries and problems—one by one—created trust between us and eventually convinced everyone to give lean a try.

Introducing lean thinking and practice at Ngami

The time we took to lay the foundation for the change made a big difference to the extent of the resistance to the implementation. We knew from the start that Ngami would be different, and so it has proved to be. As the books tell us, implementing lean is situational. Our culture on the edge of the Kalahari is unique, and introducing lean tools and principles called for a unique approach based on simplicity and fun.

Time, for instance, seems to have a different meaning in Africa, so we had to work extra hard to explain to our people that a speedy and efficient service is something our customers value. To show them the importance of time in our workshop planning, we used an abacus, assigning 10 minutes to white beads and 60 minutes to red ones. We made it as visual as we coul

The bottleneck we were experiencing in the wash bay became visible to everybody when we started to use little car models on two shelves with pieces of paper illustrating half-hour time slots. At the same time, we began to map the vehicle’s movement across the dealership using a Vehicle Control Board with magnetic chips.

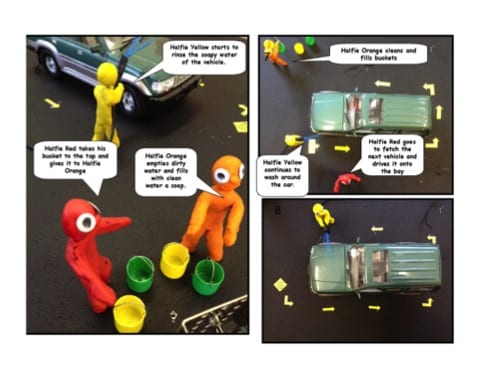

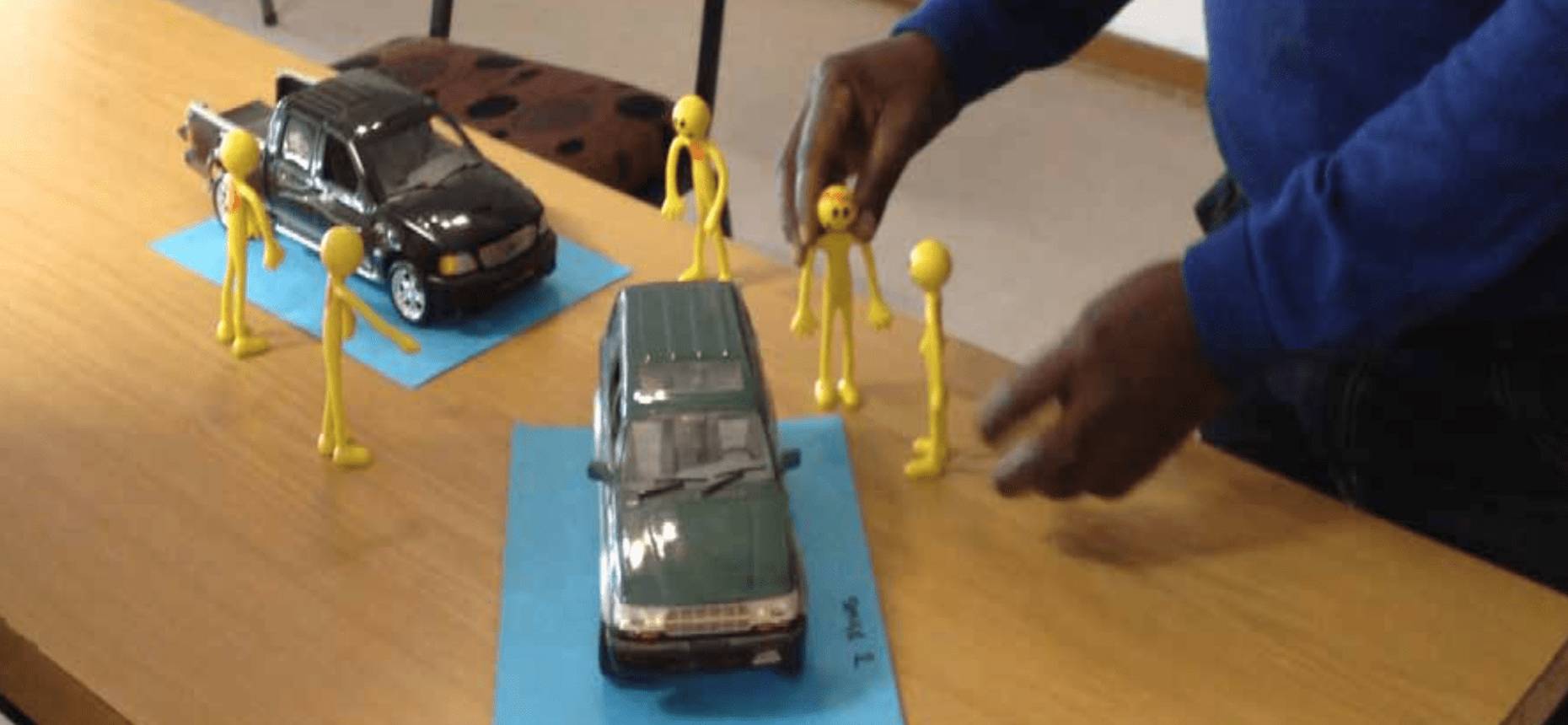

Once they grasped the fundamental mechanism of the process, we introduced standard work to build quality into our services—another meaningful way in which we provide value to our customers. For example, we used figurines of men made in red, orange, and yellow Play-Doh (which we nicknamed Halfie Red, Halfie Orange, and Halfie Yellow) and model cars to break down the work in our Wash Bay and to assign specific tasks to each of the people there. You can see an example of this in the comic strip below.

It’s all about communicating in a way that people can understand: using toys to explain purpose, movement, and directions made all the difference for people who are not familiar with diagrams and schematics.

It’s all about communicating in a way that people can understand: using toys to explain purpose, movement, and directions made all the difference for people who are not familiar with diagrams and schematics. It also unleashed their creativity and ability to solve problems. Once people were allowed and enabled to participate, the energy and engagement exploded. Staff members explaining thinking and changes to other staff members took on a completely different dimension using the toys.

We do very little classroom training at Ngami, focusing instead on learning at the gemba. What people see on a PowerPoint slideshow, they forget; what they learn using stickle bricks will stay with them forever. When you talk to people in the right way, their desire to learn will prove almost overwhelming.

Soon after standard work, we introduced the concept of kaizen, aware that it can only be done after watching and fully understanding the work. Over time, Dave shot dozens of hours of footage (it is so easy with phones these days): videos allow us to see together and learn together and act together. When you can see the work is when real learning happens. Watching a car being washed, for example, highlights problems in the process, and once we know what the problem is, we can start thinking about potential countermeasures.

Improvement is not rocket science, and kaizen can be as simple (and cheap) as using plastic gutters for draining oil filters, as shown in the picture below. Do you want another example? We used to pack wheel bearings by hand, but after we started using lean, our staff designed our own tool (using plumbing supplies) to pack them, which resulted in 20-minute savings in the time required to complete the process. The critical lesson we learned here is that kaizen must be done by the people who do the work: when they are involved, they thrive; when they aren’t, they simply nod and carry-on doing things their way.

Later, we taught them about flow, introducing important changes to the way we work. With the batch logic we had employed for so long, it took us 31 minutes on average to wash a vehicle, and the quality of the service was poor. Today, we wash cars in a single lane around the wash station, completing a wash every 16 minutes with consistent quality. We learned that simple automation could take precious time off the process when we built a drive-through wet-and-soap station (using inexpensive components bought at a hardware store), which saves us five minutes for each vehicle we wash.

There is more. To deal with the unpredictable work that too often interrupted flow in our service and repair processes, we created a Pre-Diagnostic Bay, where we inspect vehicles before the formal process begins. Vehicles leave the bay with a checklist indicating all the problems detected, which allows us to secure quotes, parts, and approvals ahead of time. As a result, we eliminated all the stagnation that previously occurred on the lifts; the technicians can now do the work from start to finish without any interruption or delay; and we experienced a 20% efficiency improvement over the entire workshop. We don’t know of any other dealer who has tried this, but it dramatically improved the productivity of our operation.

Our experiments with flow brought huge benefits to Ngami, but we hit something of a roadblock when we reached the 30-vehicles-per-day milestone. The reason? The administration couldn’t keep up with the increased volume of vehicles. So, we started mapping our people’s skills level in the office and, for each vehicle, assigning tasks to the right folks based on their knowledge and the amount of time needed to complete each task. Following that, we were able to put the admin work into a single-lane flow (I can’t stress the importance of 5S enough)—which had an immediate impact. As a result, we can now process up to 50 cars in a day without a fall down.

The impact on our financial performance has also been remarkable: between 2013 and 2015, our average monthly turnover grew by 57%, our average monthly profit by 111%, and our freed-up cash by 161%.

Our traditional way of working meant that we could expect, at best, no more than four or five jobs per day from a lift. With the introduction of lean and flow, we can produce up to five times that number from a single lift. The impact on our financial performance has also been remarkable: between 2013 and 2015, our average monthly turnover grew by 57%, our average monthly profit by 111%, and our freed-up cash by 161%.

Leading with Respect is Essential to Success

Despite having started its lean journey three years after most of the other Halfway dealerships (most of them are located in South Africa), Ngami caught up and even overtook many of them in less than two years. We are very proud of what we have accomplished.

Ngami’s success would not be possible without the active participation of our people, which in turn, we couldn’t achieve without showing respect. As a leader, lean thinking seemed like a natural way of approaching change, probably because I, too, struggle to cope with vast quantities of information. I am not a particularly fast thinker, and I need to sort and organize information. Early on, it occurred to me: how could I expect my people to understand the work if I didn’t?

I have learned that lean is often about turning our weaknesses into strengths, but, to do that, we must first be humble enough to recognize we all have our limits.

I have learned that lean is often about turning our weaknesses into strengths, but, to do that, we must first be humble enough to recognize we all have our limits. Sadly, this isn’t easy in the traditional business world (in Botswana and elsewhere), which awards leaders for showing how clever they are rather than for making the work as easy as possible for their people to do.

We are nothing without our people. Make caring for them your focus, and lean will honor and reward you. At Ngami, we see examples of the meaningful impact of providing employment all the time. A recent example: a newly hired worker recently passed her probation period and became a permanent employee, which meant that she could afford to bring her child home to live with her as she previously had to live with her grandmother, who lives 500 km away. And this, in my mind, is the sort of thing that truly matters.

This article was originally published on Planet Lean, with the headline “How humility transformed a car dealership in Botswana,” on January 5, 2017, and posted with permission.

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.

This is a beautiful and inspiring story. It brings together the essentials of Lean: Respect for People, Continuous Improvement, 5S, Challenge, and more. Thank you for sharing it. 🙂

Agreed!

x2