(During The Way to Lean, a free webinar on the “lean trilogy” approach to deeply understanding and applying kaizen daily, we received more questions than presenter Michael Ballé could answer during the Q&A session. Michael is answering them, including the question below, in his Gemba Coach column -Ed.)

Dear Gemba Coach,

I have always struggled with convincing management about the importance of running to takt time, since the mindset is typically run as fast as possible. How would you address this issue with management?

I’m not surprised that you run into trouble with this as takt time is probably the tool that most reflects Toyota’s strategy. As it recovered from bankruptcy in the early fifties, Toyota remained committed to being a full-range automaker (contrary to the wishes of the MITI state department which thought it’d be better if each manufacturer concentrated on a specific segment). Being broke and not having easy access to capital, Toyota faced two very concrete problems:

- How to build new models on existing lines

- How to do so productively

Twentieth century business common sense centers on economies of scale: if you double the number of units made, you cut unit cost by 10% to 20%. BUT if you double the variety of units made, you increase costs by the same amount. The obvious solution is to create one production process per product and hope to saturate it with demand in order to benefit from economies of repetition. In this case, the only thing that really matters is to run as fast as possible to accelerate the payback on your investment.

This works if you can (1) invest in production facilities for every product and (2) generate demand for the lines. In fast moving and competitive markets, products seldom reach the anticipated demand (they’re not alone on the market). You might be running under capacity as the product establishes itself, then over capacity as the product hits its peak, and then under capacity again a new competitor hits the market and demand moves on.

Plan and Pull

In order to keep up with a very competitive market in the fifties and sixties in Japan, Toyota chose to build several products on the same lines in order to ramp up new products while reducing production of older models without having to invest in a full line for every new product.

In this context, overproduction is the worse waste, because producing a batch of A means not producing Bs and Cs also scheduled on the line. In order to be capital effective you need to build exactly what the customer orders. This, however creates havoc with the line and the supply chain. So Toyota resolved to:

- Plan the sequence on the line to represent as well as can be the variety of customer demand (with takt time)

- Pull all components on the basis of this line demand by replenishing what is assembled (as you open a new box of parts, you send a kanban card to the supplier to send a new box of parts).

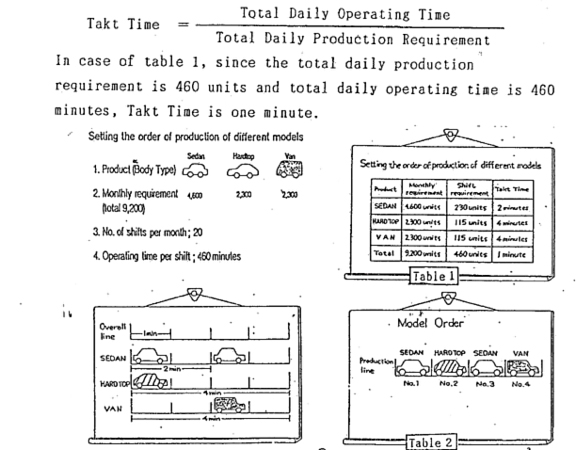

Takt time is the calculation to set the variety on the line according to customer average demand on the current period:

Once takt time is set, one can get started on the second part of the problem: handling variety with productivity.

With takt time, work needs to be achieved in a constant time increment — the “takt” — For each model, you devise a standard amount of work. Standardized work is the response to making As, Bs, and Cs, in sequence in same amount of work. Standardized work shows in real-time whether you are ahead or late, keeping up with takt or experiencing difficulties in assembly, material provision, or machine handling.

If you also set up a system to react every time you are late on takt or experiencing any other problem, such as this andon —

— then you’ll have a very tight system to follow takt time whilst squeezing waste on a daily basis.

5 Reasons Why Takt Makes Sense

All this to say that takt time reflects far more than a scheduling device. The full sense of the takt time concept appears when one is trying to deliver a number of different products over the same production resources. For instance, as a writer, I write books, articles, this column, blog posts, and tweets. Since I’m the one doing the writing, I need to have some idea of when to do what. Takt time helps me to see myself through the work: a book every two to three years, an article every three months, a column every week, a blog post every couple of days and so on. This doesn’t mean I hold myself to it, as life keeps me busy with many other things, but it gives me a reference point.

Management is seldom interested in the takt time because executives typically hold a XXth century notion that if they find the right niche and saturated it with their product or service they’ll extract all the value from captive customers. They do not take into account competitors and the fact that customers might choose to solve their problems differently. With this extractive mindset the only way to make money is through volumes and lowering unit costs.

Takt time makes perfect sense when we need to:

- Replace concurrently old products with new ones on the same production means.

- Increase the breadth of our range on the same production means.

- Be more rigorous on standards to achieve the needed work within takt time.

- See all problems as they appear.

- Learn to do things better.

I really don’t know how I would address this with management because, as you can see, in my experience, takt time hides a much bigger, strategic, issue of how we compete on our markets – and I understand if you feel this doesn’t help you much in your current predicament. Still, I feel that if us lean guys looked up from the tools to the thinking they represent, we’d have a better chance to be more credible with management, and get lean thinking adopted. No easy way out of this one!