Dear Gemba Coach,

I’m part of a large logistics organization and our on-time-delivery is simply disastrous. We’ve done a first value-stream map to improve our main delivery processes and it surfaced so many issues. We had projects to fix some, but things seem worse. We’re about to start again – any ideas on how to get it right?

Ah … yes: (1) don’t do it and (2) change your mind.

Let me backtrack. Back when I was trying to figure out what “lean” meant, I was often amused by suppliers calling Toyota in to improve their processes. The Toyota guys first asked: what is your current standard process? The supplier would be embarrassed and argue that the standard process was no good, hence the poor results and call for help.

Finally, the supplier’s engineers would pull a flow chart from somewhere and give it to the Toyota people who would point out every instance of the supplier not following their own process. The supplier engineers would then get annoyed, and explain, “Of course, we don’t follow our own process, it’s bad; That’s why we need your help, to show us how to design a good process.” And, mystified, the Toyota engineers would answer, “How can you expect us to improve your process if you don’t follow it in the first place?”

This misunderstanding went back and forth with tempers and frustration rising until the supplier’s team would finally start by following its own process, see the problems as they appeared, and, coached by Toyota, learn to solve them one by one until, one day, the “process” looked completely different (by which time, senior management would conclude Toyota had installed a Toyota-type process, which needed to be rolled out across the group – sigh …). Voilà.

Process Friction

The odds are that your main process is no more stupid than the next one. It was designed by smart people and probably wants to deliver on time.

The problem is something else entirely: let’s call it “friction.” There is an ideal way of doing the work, and then everyday stuff happens:

- Customers have unexpected requests.

- Some staff members don’t show up on time (or don’t know the job as well as they should).

- Equipment suddenly won’t work as it should.

- Key information or materials are late or can’t be found.

- The habitual work method doesn’t work in a specific case.

- Our operations weren’t designed for rain, cold, heat, etc.

- No one has the same opinion on how to deal with all previous issues.

“Normal” failure is easy to explain, whether in failing to get your rental car or blowing up a nuclear power plant, normal accidents have the same psychological basis. Anyone can deal with one thing out of the ordinary, as long as you notice it. Then maybe a second. But if a third occurs at the same time, the brain simply stops and all reactions become panic reactions that make things worse. Problems can then cascade into catastrophe, and the day is shot.

Sure, there will be some repeatable, fixable, silly things in your overall process, and you will find them – such as having the resources always at the wrong time. In maintenance operations, for instance, often most of the work is done by the night shifts, and all management happens during the day – go figure how that works.

Start Here

But really the starting point is teaching people to better understand the incidents they face and learn to better deal with them – to get closer to delivery.

One team member doesn’t show up at a critical post – what do you do? Try to do the job without them? Get someone else (how)? Do the job yourself? On the gemba, these are often intractable problems to solve because

- nothing is designed to react that fast, and

- the management approach that should be helping you solve it, typically tells you to deal with it as best you can.

The accumulation of such issues both explain a large part of your poor performance as well as “dirty the window” so you can’t understand which structural parts of the process need to be solved.

Typically, OTD issues are NOT a process problem. They’re a frontline leadership problem. Rather than “how do we optimize the delivery process?” let us change our minds and ask a different question — “how do we train frontline management to better recognize, interpret, and counter the myriad different daily issues they face.”

If you’re really serious about improving your OTD, there aren’t a million ways to go about it. You’re going to have to do the hard work:

- identify who are the frontline leaders in the process, and

- help them familiarize themselves with the incidents that can occur and how to deal with them.

This means first visualizing clearly what needs to be done – how can you come up with clear, visual, time markers so that everyone can see what needs to be done when.

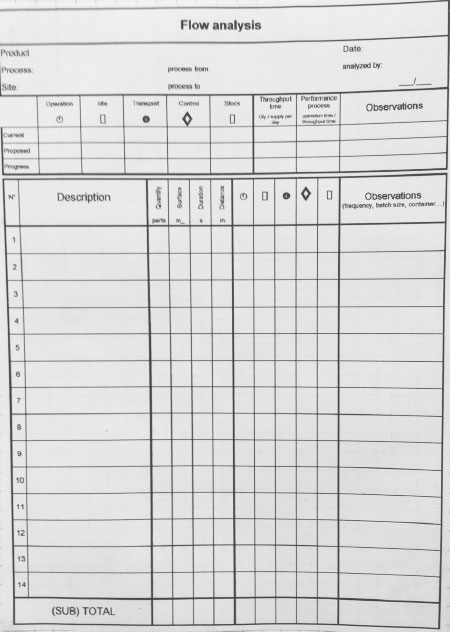

Then, help them better see the issues they come across. Back in the day, we used very simple activity analysis sheets to look into what happens several days in a row:

The idea is not to solve every problem, but to look differently at key activities and discover what kind of hiccups they can encounter.

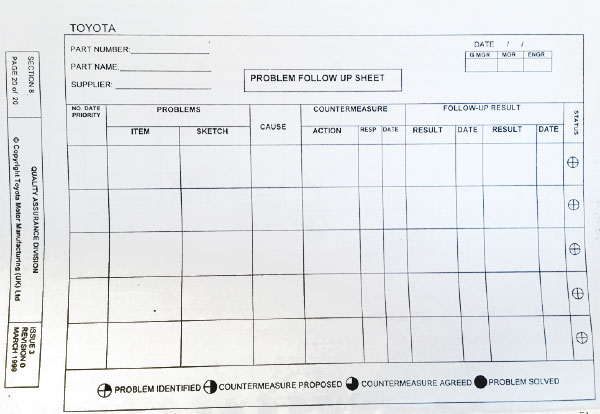

And then support problem-solving activities with the classic Toyota sheet:

What you need to change your mind on – and that of your colleagues – is that these sheets are not about “fixing” the process, as such, but about familiarizing frontline team leaders and managers to the kind of problems staff routinely experience and start coming up with a short list of “typical problems/typical countermeasures.”

The priority is to reveal problems so that everyone can start agreeing on both what abnormalities are and how they should be handled, maybe not in detail, but in spirit so that, in the end, we collectively get closer to 100% on-time delivery.

Then by asking “why?” repeatedly, you will be able to surface the root cause of some of these problems, hopefully, solve them, and in due course, indeed, improve the process.

Progressively, if you can hold your frontline managers to a regular schedule of observing their own team’s activities and debating the right and wrong ways to react, they will start to recognize:

- When they are in a known situation (the incident is known, and a typical countermeasure is known) or when they are facing something new or out of bounds and must call for help immediately.

- What kind of leeway to give each team member in typical cases to take initiatives that help to reach 100% delivery rather than let bad things continue to happen.

- What is a clear line-of-sight for success for everyone so that every team member has a better understanding of what behaviors and reactions make the process succeed as a whole, and what hinders it.

To answer your question directly, don’t try to optimize the process. First, teach people to run it as it is and deal with the daily friction they encounter. Then, as they learn to solve problems, as “why?” to figure out which problems are truly accidents, and which are caused by our own faulty planning of resources or lack of support. At that stage, yes, you will probably end up with a new design for the process, that will emerge from everyone’s commitment and hard work and that will be implemented as you go, from everyone’s input.