Dear Gemba Coach,

We’ve been quite successful with lean in our operations, and I’ve been tasked to bring it to headquarters. We’ve set up obeyas and stand-up meetings in all departments, and people are putting all sorts of information on the wall. However, I’m not sure we’re looking at the right things – any advice?

Tricky. Yes, when you start creating obeyas in office departments, suddenly all sorts of things pop up and it’s often hard to see the relevance. Furthermore, when the team has put things on their walls, whether PowerPoint indicators or holiday post-cards, they get very attached to them and it’s hard to make them change.

The first idea to communicate is that obeyas should evolve and that the whole point of PDCA is change – try one change at a time. Done mindlessly, obeyas can quickly become one more tool to defend the status quo (remember the status quo often benefits someone), so visual management has to be explicitly introduced as a tool for change, a crucible for applying the lever of problem-solving, and not a place to justify and rationalize what we’re currently doing.

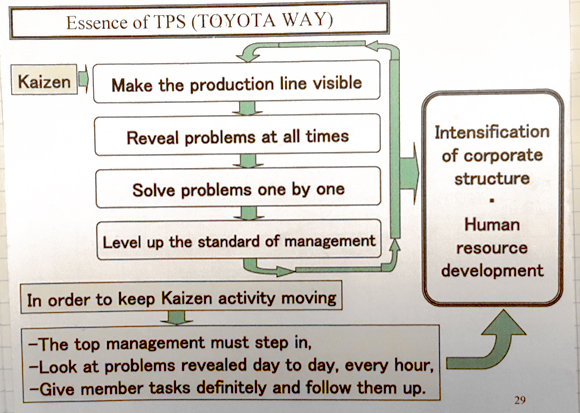

If we get back to the basics of lean thinking, the lesson from my father’s sensei is the following:

What, then are we trying to visualize with any visual management system? Essentially three things: abnormalities, work standards, and progress status.

In production, this is already a struggle (trying to get logistics to paint lines on the ground to visualize a truck preparation area), but in an office environment, it becomes a real challenge mostly because nobody knows for sure. You will have to figure out four aspects of teams’ work:

1. What is their delivery? What exactly are they doing, how does this appear in terms of actual delivery, and where is the queue? Developers, for instance, generally deliver user stories, which is code. But what about customer service associates — responses? e-mails? Visualizing the delivery and the queue is often a challenge in office work because we’re not dealing with a highway of cars all going the same way, but more of a roundabout with various different tasks to be done through the day.

In production, we do this with kanban, so that’s not so much an issue – other than the resistance to putting the kanban in place. At least, the technique is well known. In office work, it’s much trickier, because we often don’t know what the main delivery is. People know the work they do, of course, but the delivery itself tends to be a fuzzy area. A good place to start is to ask the team to see itself as a micro-company and draw main outputs to “customers” and inputs from “suppliers” (see graphic at right).

In production, we do this with kanban, so that’s not so much an issue – other than the resistance to putting the kanban in place. At least, the technique is well known. In office work, it’s much trickier, because we often don’t know what the main delivery is. People know the work they do, of course, but the delivery itself tends to be a fuzzy area. A good place to start is to ask the team to see itself as a micro-company and draw main outputs to “customers” and inputs from “suppliers” (see graphic at right).

From then on, you can pick the main delivery flows and scratch your head with the team to visualize physically the delivery, whether with cards, plans, whatever. Typically, in engineering, I tend to do it like this:

2. What is an abnormality? What are abnormal conditions? In the above plan, abnormalities are triangles – when the project didn’t end when we thought it should because it hit a snag, written on the right-hand side column.

But truth is, in office work, at first no one really knows what is normal and what is abnormal. When you visit accounting and handling of vendor invoices, for instance, about one in ten has an issue, so rework is seen as the normal work. There’s no help for it, you will have delve into understanding what “problems” are and, yes, at first, all sorts of things will crop up that are neither really problems nor really relevant. The difficulty is to know which is which.

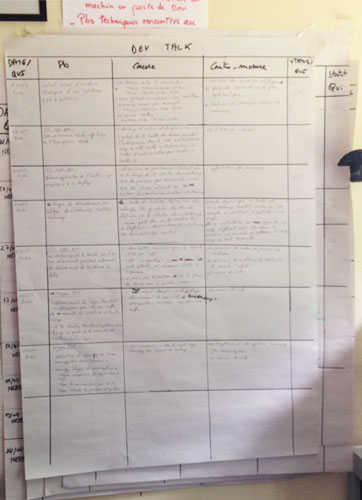

I usually start with a simple flip chart to write problems as they come up:

But that’s just the start. The aim here is to get a sense of what “typical” problems are, such as manpower, machine, materials, method. Out of all the possible issues that are surfaced by teams we need to progressively get a sense of what, exactly, is an abnormality (is it a bug or a feature?).

This is a crucial step when setting up visual control. The team will first consider that everything is normal, then will switch to everything is a problem. Distinguishing normal form abnormal is a critical part of getting hands dirty and familiarizing oneself with the work, which will involve looking into boundary conditions – at what point the normal becomes abnormal.

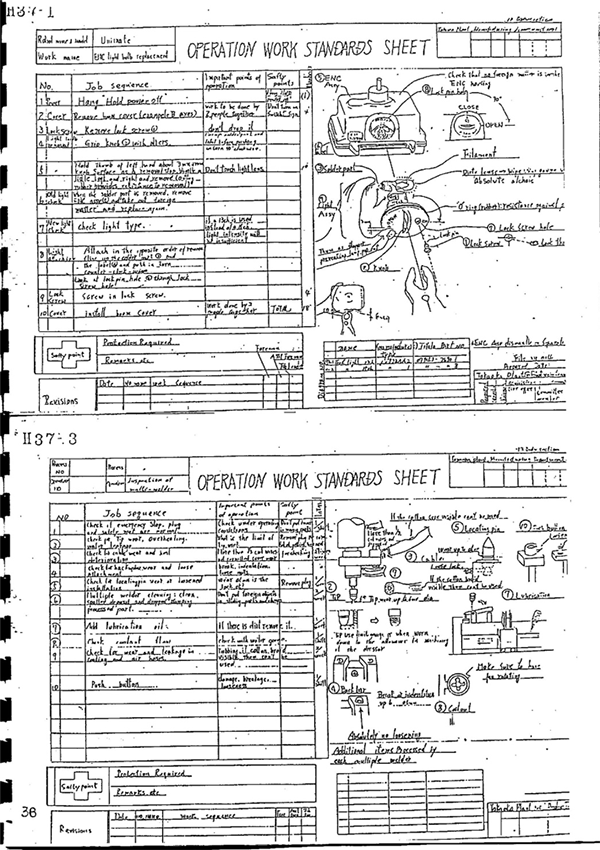

3. What are the standards? Standards in lean mostly mean an explicit sequence of steps to do a job well while generating the least waste, with a special focus on the “critical-to-quality” points. In production, a work standard will look something like:

In office work, it’s really, really hard to establish such standards, mostly because it’s never been done before. Again, no help for it, you’re going to have to delve in.

For instance, one of the most personally unpleasant things I occasionally have to do is hosting conferences – as an introverted writer, I find it even harder to do than actual keynoting. After messing it up for years, I’ve finally written up a standard:

|

STEP |

KEY POINT |

|

Smile |

I mean it: smile |

|

Introduce the speaker by telling the audience how this is an extraordinary person, with an extraordinary journey and an extraordinary, inspirational story to tell and say how proud I am to introduce them |

Get their name and job right |

|

Get the audience to clap |

Clap |

|

Stand up and get closer to the speaker to signal the end of the speech |

Make sure someone gives them visual time signals |

|

Thank the speaker |

|

|

Ask them one question: was there a breakthrough “aha!” moment? Was there a particularly emotional moment you want to share? At what time did you realize that…? |

Be on the lookout for the one question that will make the speaker look good as you listen to the talk |

|

Take questions from the audience |

Shut up |

|

Ask the speaker for a last takeaway |

|

|

Smile and clap |

|

|

Shake their hand |

Hand on elbow, as you lead them off stage |

|

Welcome the next speaker |

Remember the next speaker is stressed, so be friendly |

Now, I’m not a professional speaker, and this standard should be the first step to further kaizen, but having the standard at least shows me every point where I slip up and miss a step.

I use this example here to illustrate that you can start writing standards on the most unlikely tasks – it’s just a way to clarify what you know about the task and what you don’t know. In office work, people will tend to write “standards” about things everybody knows but doesn’t do, such as “leave the toilet clean after using it.” This, in general, is not very helpful – not a skill issue, a will issue. Standards really are about clarifying the unclear parts of the job so that we can spot abnormalities and start working on them.

4. What is the progress status? The surest source of motivation is to see your progress, your team’s progress (we’re progressing together, which gives us a social high), and to be proud of the company where we work, which is at the core of the lean challenge: how do we align personal fulfillment and corporate destiny.

Reacting to abnormalities and solving problems is essential to developing people. With adults, there’s no way around it – we learn through experience. But it can also feel thankless and endless. We need to see some measure of progress, both in the day and in the job so:

- How do you visualize success for the day?

- How do you visualize progress in the job?

In office work, production analysis boards with “parts by hour” rarely make sense. You’re going to figure out how to draw this out of the team. To get started, I use a simple whiteboard where, at the stand-up meeting in the morning, the team leader lists the few key things we have to get done today to consider the day a success.

This is not as simple as it looks, and often needs to be prepared the previous evening with the frontline manager. It’s a starting point before you get to more structured visualization of progress through the day – and it’s a great way to discover what the teams have to do as opposed to what they think their job is.

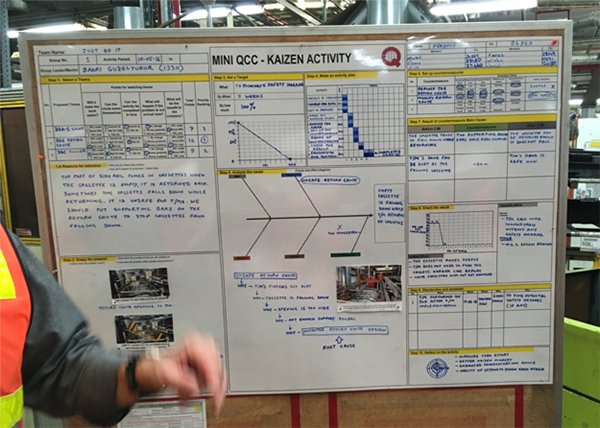

And finally, there must be some space for at least one kaizen effort or project, something that demonstrates the team is improving the way it works, that it is progressing. It can be as simple as a paperboard sheet on the wall explaining what the team is looking at. Or a whiteboard with a structured kaizen story:

And your intuition is absolutely correct – at first, what goes up on the wall is generally nonsense. Making the process visible, revealing problems, solving them one by one, improving how we manage situations, jumping in and encouraging kaizen, none of this is natural – it’s an acquired skill.

At first, people will use the visual control to do exactly the opposite: hide the real process, snow you with problems that no one can solve right now, explain that nothing can be done, write nonsense instructions and motivational messages all in the – often unconscious – hope of validation of what they’re currently doing, protection of the status quo and reluctance to accept that, yeah, for real, we’re going to face problems and improve stuff around here. And that’s okay.

Your job is precisely to babysit them through the learning curve until progressively, the process becomes visible, abnormal conditions appear and the corresponding problem solving, key standards are posted or written up somewhere and studied regularly (through “dojos,” for instance), and progress, both during the workday and for the team, is visible at first glance.

Obviously, “at a glance” is the success criteria for visual management – the more intuitive it is, the lower the cognitive load on each person, and the deeper they’ll naturally trust and use the system. Learning the visual ergonomics of “at a glance” is our job, and not an easy one: a good topic for developing our own standards?

Setting up visual management in the workplace is not something you can roll out and move on. Let’s face it, you’re going to work at this progressively with every team until it comes together in a way that makes sense for each team as well as bringing the work together for the entire company in order to, in my father’s sensei’s words “intensify corporate structure.”