Dear Gemba Coach,

Obeyas are popping up everywhere in our organization, and I don’t know what to look for to distinguish good from bad obeyas. Any pointers?

Very good reflex! Deming 101: What are the operational criteria to distinguish a good job from a bad job! Unfortunately, hard question to answer as there is clearly not one way to set up an Obeya. Let me have a try.

First, let’s take a step back: What is an Obeya for (Obeya means “large room” – a room where people meet and discuss according to the information posted on the walls)? What is the problem the tool is supposed to address? What are the missions of the people regarding this tool? Which gains are we looking for and where?

An Obeya is clearly a tool of teamwork: helping managers in various functions solve problems across their borders. As part of a project or management team, what the Obeya should give you is a clear idea of what your colleagues are working on and why (as well as why they think what they’re doing is helping) so that you can see for yourself where your own efforts help them or cause them additional trouble.

Obeyas are a tool for voluntary alignment, not, as I unfortunately often see on the gemba, for better piloting projects. In most companies, functional heads keep clarifying turf – sorry, roles and responsibilities – so that boundaries are clear, no one is stepping on anyone else’s toes, and we can all be good friends at lunch. The deeply ingrained idea is that if only everyone did their part of the job, everything would work smoothly. This is plainly silly.

What makes an operation effective is the ability of different specialists to work together in order to fix their collaborative handover problems. Indeed, this is where, in lean, a pull system, from the customer to engineering to what we see in production is the most powerful. As you follow the cards, you need to work with your colleagues to create the successful delivery here, now! (which is the opposite of following budget lines, which is a zero sum gain as everyone tries to push part of their costs on the next door department).

To visualize it, I was very struck once reading a book about commando teams sitting down together for a “walk through, talk through”: walking through together every minute part of the plan and discussing what they might have a difficulty with and how they would better coordinate to use their individual specialist strength in that situation. A lengthy and somewhat boring process that is however critical to the success of the mission. Clearly, plans never work out as something else always happens, but planning is critical. The skill being developed is not actually about planning, but understanding each other’s operational parameters and interfaces. Collaboration.

The Obeya should, therefore, represent clearly four topics:

- What is the goal (or goals) of the mission?

- What is the plan?

- What are the hard subjects to crack?

- What specific problems is each team member working on to do so?

The Big Question

In lean the big question is always customer satisfaction. This is where lean is the most disruptive. What do we need to do to ensure “one time customer, lifelong customer.” This is our reason to all be here together: not run departments to upgrade systems, fight fires and survive another day, but convince customers that they’re better off with us than with our competitors. End of story.

So, if you walk into an Obeya without a full section dedicated to customer complaints and quality measures and issues, you can simply walk out again.

For instance, I was on the gemba of a maintenance operation recently, and the Obeya has visualized in great detail the turnaround lead-time of key equipment, which was great, but there was no measure of… breakdowns or slowdowns. No striking representation of whether the team was not just doing the maintenance on time, but actually succeeding at keeping the machines running. This, by the way, is incredibly frequent. Hospitals won’t measure and display hospital-acquired infections, train stations don’t display trains leaving on time, etc. Everyone keeps measuring lagging or financial indicators, not what tells you how well you’re doing right now from the customer’s point of view.

Typically, quality is not the only part of the mission. Safety always and quality first, but we are here to improve value which is function over costs, so there may be other key indicators to represent other aspects of success: on-time-delivery, total lead-time, inventory turns, first-pass-yield, and whatever else is relevant to the specific mission.

Then there should be a plan there – not a detailed Gantt plan necessarily (these are dangerous because of the constant rescheduling), but a clear visualization of the key milestones of our plan: the meeting gates we need to reach on time, the trains we need to catch in order to succeed. These have to be very clear, so that everyone on the team has a clear reference point of collective “must do, can’t fail.” Don’t be late at the rendezvous because the ship sails with the tide.

Now, obviously, a plan is a fiction. It assumes that everything planned will, or indeed can, get done. In truth, the plan hides a couple of really hard things to do (not always known at the outset because this is very context dependent). Think about an action movie storyboard – the writers usually start with the “set pieces” the impossible things the hero will have to overcome, and then they write the story around them.

Why Obeyas Fail

These should have a dedicated area in the Obeya. A technical area, not a planning one. One where the product or service appears in detail, and in its full technicity. One where you can, from any department, see how it has to fit together to satisfy customers in terms of performance, quality, and price. Here we need to see the problems from all angles – to understand both content and context.

This is where most Obeyas fall over. People love post-its and turning difficult technical issues into high-level phrases, but are far more reluctant to expose their deep problems in all their impossible glory. This, however, is where success lies.

The radical management innovation of lean is to spend time understanding problems more deeply rather than managing the implementation of solutions to just get it done and get ahead and sort out issues later.

This is where the rubber hits the road. The ability to represent the hard things to do clearly, in detail, so that every member of the team can delve into it and, critically, understand issues away from their own area of specialty and expertise. In a way, this is where we forge the management’s team “competency matrix” and strive to develop more competent managers – they don’t need to know how to do each other’s job, but they really need to understand the critical, make-or-break issues in each other’s job.

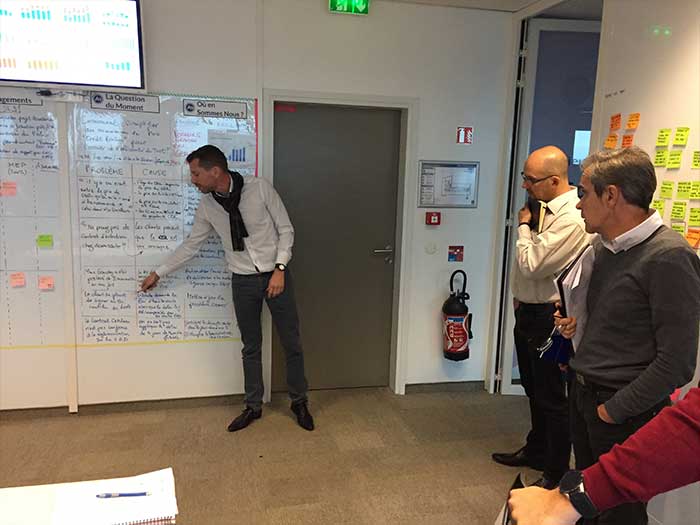

At Aramisauto.com, a digital and multi-brand automotive retailer in France, a manager leads a team review in an obeya room that uses digital and whiteboard displays of information.

Finally, there should be a spot for individual plans: goals, targets, problems (often A3s) and action plans.

The first part of the Obeya is about constantly clarifying the collective mission, the job we’ve got to do together. The last part is about understanding how each of us interacts, and how we help or hinder each other.

This section of the Obeya should visualize each person’s individual efforts to contribute to the collective problem, not to track how well they’re doing, but to make others understand:

- What they’re trying to do

- Their thinking behind their actions

- Where it overlaps with what others are doing

Therefore, the mission of the managers as regards to the Obeya is to keep the collective part up to date, certainly, but more importantly to present to each other their own progress and obstacles. The simplest way to do this seems to be a calendar of A3 presentations – once a week, the team meets up to hear one A3 by one member (which gives each person a number of weeks to prepare their own A3s in turn). This is a moment of reflection, not argument. Ideally, one person presents their A3, the others ask clarification questions the presenter has the discipline to note down comments and not respond. These will tend to be hard questions because departments interfere – rightly so. We don’t want to trigger the justification/rationalization cycle, just more mutual understanding. The best way to do that is to hear, not reply, and think about responses (change something, explain something better) after the meeting.

Again, the Obeya is a safe space to forge voluntary collaboration (which, okay, let’s face it, might require a bit of encouragement from the boss). It is not a place to control the progress on action plans – plenty of other management systems are in place for that, and I’m not suggesting we stop rigorous plan follow-through supervision.

Obeya Benefits

What gains can we expect? Where to look for them? As a leader, this is probably the most disconcerting aspect of Obeyas. My own experience is that results improve, as seen in the key measures, as the grasp of problems progresses and the teams forms a common, deeper understanding of the hard things. As they do so, they learn to trust each more and work together better. This is counterintuitive as a boss because we’re not looking for more success reports or friendlier exchanges. On the contrary, we look for:

- More disclosing of hard problems with no obvious solution in sight

- More heated exchanges, because we understand that emotions are a key part of expressing difficulties to each other. The real stuff is never bland.

I recently attended a brilliant keynote from a leadership and motivational speaker Stephanie Voss who suggested the three dialogue killers were:

- Who started this?

- How did we get there?

- Who is to blame?

Of course, she is right. But then again, since this is completely how our minds work, better accept it rather than suppress it. The leadership challenge is to create a safe and goodwill environment to let people say tough things badly. When it’s difficult for them to express, they will get riled up, or shy, or awkward, and yes, the first expression is likely to be “not my fault, they’re to blame.” Fine. It’s okay. The leadership challenge is to remind everyone we’re on the same side, and we may not be friends (personal is personal; some stuff about each other will drive us crazy, no matter what), but we can be comrades, allies.

Teamwork is emphatically not about agreeing on what we already all know in common. Teamwork is about listening for the unique knowledge that one person has and the others don’t. My rule of thumb of Obeyas is “how do we help customers solve their problems by putting together the unique knowledge of every person on the team?” If the Obeya does this, whatever its shape, look, form, it’s doing the job!

What is the difference between Control Room (Tier Accountability Boards) & Obeya Rooms ?

What is the difference between a good & bad control room