Dear Gemba Coach,

We used training and workshops to roll out a lean program with good early results – what do we need to do to ensure sustainability?

Any improvement program, lean or otherwise, will deliver results in the first couple of years as (1) management invests heavily in coaching support and (2) coaches and teams discover low hanging fruit, obvious wastes, and fix them. Typically, programs run into the sand in the third to fourth year, with a spreading variation between the teams that progressed and those that did not. And then, even the fastest teams seem to slow down and revert to the mean as the coaching/consulting pressure is reduced.

Worse, no matter how much “savings” these programs generate, we rarely see them on the bottom-line (which is when lean crazies start arguing that the bottom line is not the yardstick for lean success – which is true, but still a dodgy argument — the bottom line always matters).

No matter how much management teams try hard to ignore this, there are some very real reasons for this process. Most organizations are both (1) highly coupled (when you touch something somewhere it impacts the organization elsewhere in unexpected ways) and (2) loosely linked (the interfaces between parts of the processes are vaguely defined and there’s a lot of passing the work over the wall). As a result, as you can imagine, if you start randomly fixing issues here and there, sometimes you get lucky, but overall, you’re not changing how the business actually operates. It’s like squeezing a pillow: squeeze here, it will bulge there.

Intent and Kaizen

To make any lean effort sustainable, the CEO must first clarify its intent – what is he or she trying to achieve. For instance, when the CEO of a chain of car dealerships started a lean program, the problem he had in mind was clear (yet complex): he wanted to reduce the waiting time to deliver cars to customers. Due to the complexities of his supply chain and variety of customers’ special demands, this was no walk in the park, but at least the question was clear-cut.

Then the skill to conduct kaizen must be acquired. The CEO hired some lean coaches and got kaizen started at various points of the business: in the showrooms, in the service areas, in the parts supply centers, in the logistics offices and so on. At first, coaches were doing any kind of workshop, but soon enough, the CEO got them to focus on a structured standard method – close to Art Smalley’s and Isao Kato’s six steps described in Toyota’s Kaizen Methods.

This programmatic approach had the unexpected result of revealing far more issues than it solved. As he visited the kaizen workshops on the gemba, the CEO discovered an increasing number of issues, such as:

- Salespeople did not know how to offer a more readily available vehicle when customers were open to switching preferences, such as seats or car color, in order to get the car faster.

- Salespeople did not use service opportunities to suggest trading up.

- The logistics team tried to reduce the transport cost by unit, adding to long delays.

- Sales offices didn’t understand the admin info needed for the logistics team to deliver the right car at the right time.

- No one was trying harder to negotiate with automakers to get cars faster.

- The dealerships were separate businesses and did not know how to trade cars easily among themselves to satisfy customer requests.

- And so on.

Overall, the CEO discovered three hard facts:

- Interesting improvements at the local level were unsustainable because corporate implicit or explicit rules acted as a rubber band to pull the new ways of working back to what they always were.

- His main difficulty was getting his central corporate directors, the heads of each function, to take an interest and learn to work together as opposed to solving their own functional problems irrespective of business aims.

- Gemba difficulties varied enormously from one dealership to the next, according to individual skill and experience of salespeople – both with selling and with handling internal systems.

This pretty much describes what a functioning lean program should look like. First, the top leadership should have a clear aim of what they intend to get out of the program. The unique lean focus many people take a long time to learn is that focusing on internal flexibility improves customer quality and delivery and reduces total cost by liberating capacity. This won’t happen on its own, you’ve got to seek it.

Facing Your Weaknesses

Second, the leadership needs to understand that kaizen results, the improvements themselves, don’t come out of “fixing” the process with Taylorist methods, but engaging people in the mastery of their skills and work environment. This means confronting their own weak points through PDCA: facing up to a weakness and planning to do something about it (Plan), struggling through trying to do something different (Do), visualizing and keeping the emotional distance to see whether that works or not (Check) and drawing the conclusions to adopt, abandon, or adapt the new method until it sticks (Act). Results are achieved by each individual’s energy in owning up to doing something not well enough and exploring how to do it better, which, in turn, requires a work environment supportive of self-development that is: (1) GUILT-FREE, so you can own up to not being perfect or take well-meaning criticism and (2) SAFE, so failing is preferable to doing nothing – which requires both (3) TRUST and some degree of fun.

Third, kaizen activities only make sense if the top leaders take an interest, go to the gemba and try to figure out what the organization does that makes the kaizen necessary in the first place. Discoveries are made by accident, but they occur to people who seek. By looking into kaizen effort after kaizen effort, leaders can figure out what their central organization does to either support frontline staff or hinder them – which mainly has to do with teamwork at the top management team level. By getting functional heads to solve problems together, the CEO can fundamentally reorient the organization and change the incentives, the rituals, and the deep beliefs towards better service to customers.

Experience with lean programs shows that these are sustained if the CEO learns to further things: (1) being clear on what he or she intends to reinvest the kaizen gains once they are obtained. This is a huge motivator for teams and coaches alike as they can see where their efforts lead and how this impacts the company; (2) sharing some of these gains, first as recognition and, if possible, as financial rewards to further deepen the trust basis.

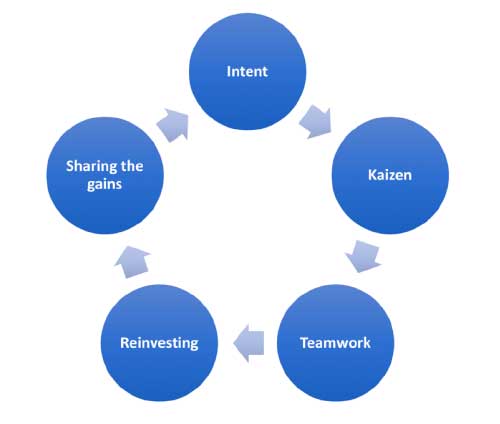

On the whole, a healthy lean program would look something like that:

And once one core issue is solved, the CEO can then move the program onto tackling the next one and so on. After a while, the key challenges of the business become clear and the program will settle down on three or four key challenges that must be faced – often, issues that were not expected at the start. For instance, in the car dealership situation, the CEO discovered he kept hitting on marketing problems (how to get customers to visit his dealerships) which led to a complete rethink from “increasing sales” to “growing lifelong customers” and communicating that – both at the individual salesperson level and at central marketing.

A long answer to your difficult question! The core idea here is that sustainability depends on the leadership’s intent, it’s clarity and follow-through. As long as the leader is (1) seeing a clear company-level improvement by (2) exploring the kaizen work frontline teams are doing, the program will have the energy to continue to deliver results upon results as individual employees feel free (and safe) to engage in self-development. The alternative, which is what most lean programs end up being, is a set of routines implemented at high consulting cost which then turn into rituals. Certainly, if you practice the same rain dance every day, some days it will rain, but that won’t make your crops grow better. To make lean programs sustainable, first, we need to understand what they really do, at intention, activity, teamwork, and sharing of gains levels.