In a recent column that Michael wrote, Ernie and I (Tracey) shared our simple definition of lean as “the continuous process of people development.”

So what does it mean to develop people? How do we do it?

Akio Toyoda often encourages his employees to “stand in the batter’s box” and to “challenge to improve.” This involves two dimensions: one, taking responsibility for outcomes based on good processes and, two, learning to achieve measurable improvements. Which is pretty much what we’d expect from someone we’d like to work with: that they take greater responsibility for helping us with whatever we’re facing by developing discipline and accountability around shared expectations This is leading and learning at its best.

Learning (and understanding) involves change. Either changing what you do to meet an existing known way of doing something, or changing how things are done to solve a hitherto unsolved problem.

If we establish that the best-known method that we agree to follow together at the moment, we are agreeing to mutual accountability until we improve it together. This baseline sets the first bar to raise in the continuous improvement process. This doesn’t mean to standardize everything, but to look at key process indicators that need to be controlled and continue to ask and engage the primary process owners to be creative and allow “space to think”.

This leads to an apparent contradiction: on the one hand, we need to follow the established process, and on the other, we need to change it to make it better.

The apparent paradox starts with the very mechanism of human learning. We, humans, learn when we see the impact of a change we’ve initiated. This largely predates speaking and reasoning. Learning, in fact, involves both acquiring culturally transmitted knowledge – in lean terms, let’s call this a bundle of standards, ritualized ways of conducting an activity – and experimenting with change to better grasp the underlying causality in how the existing process delivers the predicted output.

Theoretically, there is no real problem – you should be in one of two situations. 1) there is a clear and acknowledged standard, or someone is a reference is some way; and learning means changing what you currently do to meet this standard. In trying to do so, you’ll learn about why the standard is set this way, and/or why your role model does it this way. 2) there is no clear standard, and you see a problem that seems obvious to you, analyze it, try something different and see if it works – and keep going until it does. If you find an answer, you then convince others that this is the way to do it, and it then becomes a standard (as the history of science shows, don’t expect this to be an easy fight).

In real life, it’s very hard to know whether you are in situation 1 or 2, but the fact remains that learning (and understanding) involves change. Either changing what you do to meet an existing known way of doing something, or changing how things are done to solve a hitherto unsolved problem.

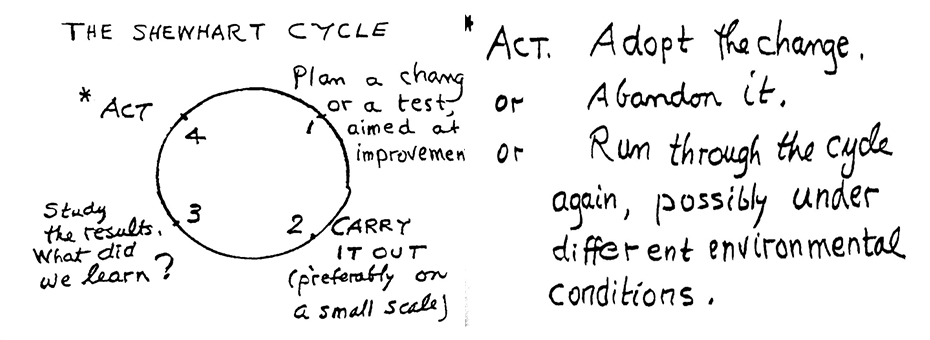

Which is the fundamental point that Deming grasped when he formulated the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle: in his terms, it’s planning a change, carrying out the change, studying the results, and either adopting the change– or abandoning it. He’s talking about intentional changes, not random “actions” (or tests, which are changes in formal controlled conditions). In fact, this is exactly how our mind works when we “woolgather” – we imagine changes and run through imaginary impacts on the simulation software of our brains. This is how we think. We act to understand.

Trouble is, although we all like the changes we propose, no one else seems to, and hence convincing others is a constant challenge and sometimes a real risk. “And yet, it moves,” Galileo is supposed to have muttered under his breath when threatened to be burned at the stake by the Church for suggesting the earth moved around the sun.

Lean is not a sum of processes to acquire and apply which then will make things magically work better. It’s a set of techniques to visualize delivery processes so everyone understands them at a glance, reveal problems to give opportunities for people to exercise their abilities to think, be creative and utilize their strengths to self-actualize in the course of their work.

Developing people, in that sense, would mean encouraging them to experiment with changes, one at a time. We don’t want them to reinvent everything every day, which would clearly lead to chaos (as we can currently see with many digital start-ups that try to reinvent everything from scratch and get nowhere fast). Somehow we want to balance changes in how they work to get closer to a known standard (which is no change of operating processes), with changes to the way things are done to find new, better ways of meeting our wider challenges.

The traditional way of running a business consists almost exclusively of the first approach: first learn every standard and every process the way it’s currently done, and then we’ll see if you earn a license to change something.

Lean accelerates learning by creating an environment where changes are easier. This works by first expecting people to learn existing standards, and then asking them to: 1) spot a problem (step into the batters’ box) 2) take responsibility for it (meet the challenge), 3) try changes one at a time with PDCA, studying results carefully, and 4) engage their colleagues once they’ve figured it out.

Lean is enquiry-based because it assumes that standards are known in the first place – which is far from true in many working environments. Assuming that standards are known and practiced, lean activities are all about asking “what is the metric that needs changing?”, and then “what are the causal factors impacting this metric?” to get to the one thing we want to try and change.

Which brings us to the answer to the second part of the question: how do we continuously develop people? Lean systems, such as the Toyota Production System (also known as the Thinking People System), are not production systems per se – they are techniques to visualize production processes so that problems are revealed and inquiries are triggered. Similarly, Hoshin Kanri starts with challenges from the top and is not cascaded as objectives to achieve but as inquiry points: which metric do we need to shift if we want to achieve the overall goal? How do we define this problem? How do we analyze the factors and narrow down on the causes with the people themselves? What do we change to understand the problem better?

In other words, if we involve all the stakeholders that do the work to create the expectations we would be bringing to life, the true meaning of respect for people and their ability to think and give them the avenue to hypothesize, run trials, piggy-back ideas and document through measurability of the process if the standard isn’t robust enough when the market asks for more. Some ideas may work. Some may need to be tweaked. And others may be scrapped based on ROI. But the fact everyone is engaged individually which supports the team – departments and upward to the true north – creates a catchball effect.

The whole point about catchball is not that people receive objectives aligned with the strategy from the top and then come up with an “action plan’” to make the numbers, but that they’re asked “how would we achieve this?”, take responsibility for one part of the problem and have the latitude to change things in order to improve what they intend to – and have management support to get buy in from their colleagues across functions.

Lean is not a sum of processes to acquire and apply which then will make things magically work better. It’s a set of techniques to visualize delivery processes so everyone understands them at a glance, reveal problems to give opportunities for people to exercise their abilities to think, be creative and utilize their strengths to self-actualize in the course of their work.

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.