With the business case for using lean thinking and practices to achieve environmental sustainability goals becoming stronger every day (see Why Lean Thinkers Should Ground Their Thinking in Sustainability), it’s time to give actionable attention to the idea. But where to start?

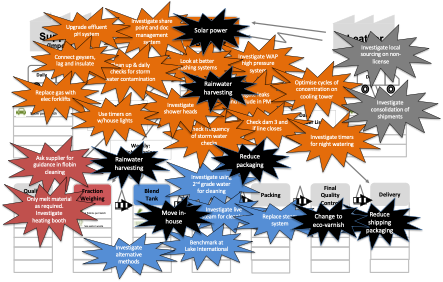

For a small chemical manufacturing site in Johannesburg, South Africa, it started where lean thinkers usually begin: at the gemba. At their plant, we walked the gemba with the management team and various team members. Viewing the work from an environmental perspective, they captured the workflow and measured “green waste” at every process step. Then, assigning a number to the waste, they converted the findings to an annual cash loss and debated solutions (as shown below). It was clear there was work to be done.

The team discussed the impact and hidden costs of non-green practices, many of which they felt were avoidable at a low cost. They also calculated tangible savings mainly attributed to energy and emissions improvements. This exploration was a motivating start that held far more learning potential.

The leaders of this chemical manufacturer understood that the cost to society and the organization of not addressing business’ environmental impact is palpable. Their gemba walk demonstrated that learning to direct lean concepts toward reducing the environmental impact of your organization has a lot going for it, so let’s explore the practicalities and meaning of this.

Lean practitioners have terrific tools at their disposal, such as mapping, 5S, and A3s. Though “just tools,” they help identify problems and encourage teams to solve problems together. Still, two practices stand out as good first steps toward applying lean thinking and practice toward building eco-lean mindsets: value-stream mapping and waste elimination.

Mapping the Green Value Stream

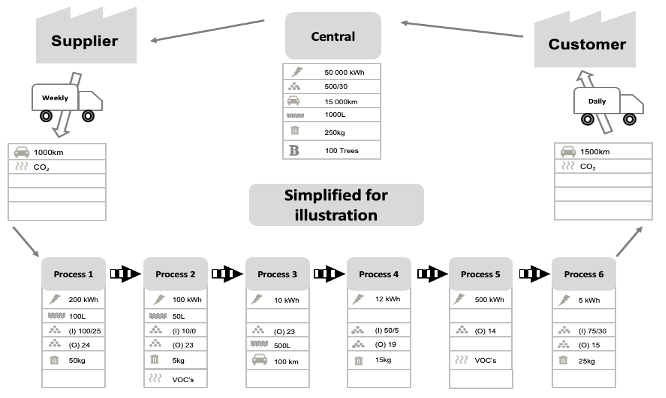

Just as value-stream mapping has helped many lean practitioners take their first steps in learning to see waste from a traditional business viewpoint, it will help them see environmental issues to address. Similarly, a value-stream map drawn from a green perspective will enable people to challenge current conditions and debate target conditions, sparking collaborative cycles of experiments and a series of countermeasures. Also, the green value-stream mapping process will develop a greater awareness of environmental issues, which will push them to set and achieve evermore stringent sustainability objectives.

Shifting focus toward green value-stream mapping is a natural progression for lean practitioners who must address increasing demands to adopt evermore environmentally sustainable practices.

Seeing Environmental “Waste”

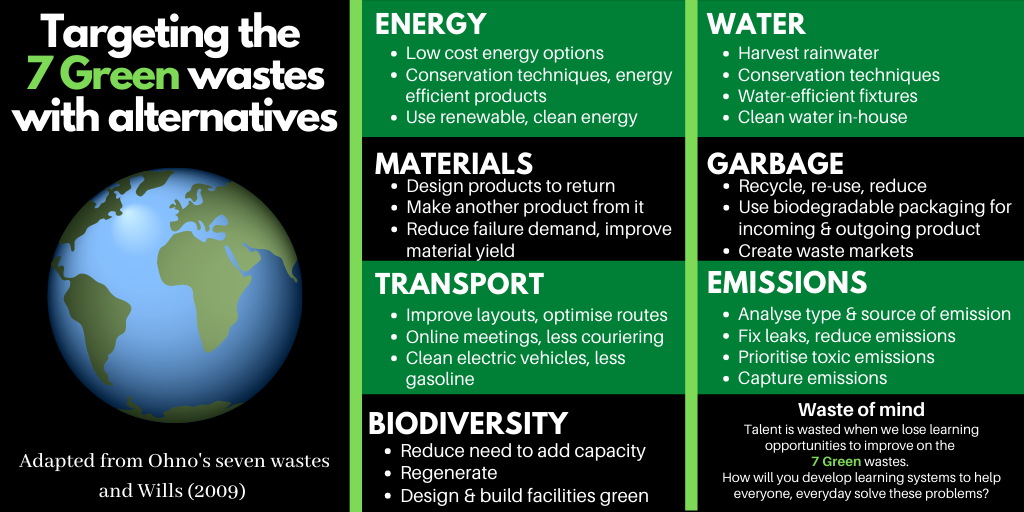

When conducting green value-stream mapping, organizations we talk to use a framework that echoes Taiichi Ohno’s original seven major wastes. Using this systems view, they look for evidence of what’s become known as the seven green wastes and the subsequent overburdening of the environment across value streams. Following lean principles and practices, they then seek facts and measure impact, framing each challenge and focusing teams on meaningful experiments to conduct. As with traditional lean problem-solving, some problems are difficult to solve or outside the team’s control, so they are backed by a chain of support and escalation route for more systemic changes.

These seven green wastes are bad for business and empower a fixed mindset that tolerates environmental degradation — and by ignoring them, organizations face many risks:

- Losing eco-conscious customers

- Demotivating eco-conscious talent

- Wasting resources, energy, and capacity

- Consuming unnecessary materials

- Paying fines and penalties

Identifying Green Waste

As Ohno’s seven wastes guides organizations, the seven green wastes offer a framework for those looking to apply lean thinking and practice to achieve their environmental sustainability goals. Of course, improvement comes naturally to many lean thinkers, but a closer look at environmental waste requires more than that. Here is what we found in our research and during our gemba walks.

- Energy: Explore whether you’re using the right form of energy. Is there a cleaner fuel available, or can you obtain electricity from a renewable resource?

- Water: Consider whether fresh water is necessary for the process or whether you can treat or recycle it?

- Materials: Closely examine the materials and how you process them. Do you take-make-waste, or have you designed out waste and pollution from your products, services, and processes? How well do you understand the supply chain that brings the raw materials to your factory gates? Does the timber come from responsibly managed forestry operations? Expanding your view toward social responsibility, has forced labor been deployed to produce the cotton?

- Garbage: Consider that some types of trash are worse than others. For example, investigate the impact your garbage has once it is out the back door. With this knowledge, you can pursue initiatives, perhaps in collaboration with other organizations, to re-use what we can, recycle what we can’t, and ensure that any remaining garbage is disposed of responsibly.

- Transportation: Though included in Ohno’s original seven wastes, transportation is also a significant cause of pollution. During pandemic-related lockdowns over the past year or so, most of us have probably noticed real albeit temporary improvements in air quality due to fewer people moving around. So, it’s another green waste to target. Looking at your supply chain, how do your raw materials reach you? When you build a manufacturing plant, can employees use efficient public transport to get to work? And recent events have shown that many of us can work remotely, thereby reducing our impact on the environment.

- Emissions: Review the types and quantities of emissions to determine whether they’re harmful and, if so, look for ways to eliminate them. Countermeasures might require choosing a different manufacturing process. For example, it wasn’t all that long ago that most sodium hydroxide and chlorine were produced using a process involving substantial emissions of poisonous elemental mercury. Moving to a membrane-cell process stopped these emissions and brought efficiency improvements too. Where you can’t eliminate emissions, you can explore how to reduce or treat them to minimize their impact.

- Biodiversity: It may seem strange to consider biodiversity when mapping the sterile processes of a hospital or the steel-housed activities of the factory floor. Yet, the very act of building a facility, particularly in a greenfield situation, may well have already negatively impacted the area’s biodiversity. So, it behooves you to consider the impact of ongoing operations. For example, the world is becoming increasingly aware of the effects microplastics are having on species ranging from crustaceans to swordfish. The material selection decisions you make as you develop your value streams may well impact our world’s threatened ecosystems.

The seven green wastes expand the improvement agenda by enabling lean practitioners to see more and put numbers to what we see, thus catalyzing green-focused kaizens. This approach does more than highlight “how much” waste and the associated potential cost savings; it targets an ideal state of net-zero emissions, long-term competitiveness, and the development of eco-conscious people.

Mapping the value streams and targeting waste from an environmental perspective will help you transition from a take-make-waste economy to one where you eliminate waste, circulate resources, regenerate natural resources – and ultimately rethink your business model. Expanding your ideas about waste and learning how to deploy available lean practices and tools will help you reduce the negative impacts of the products you make, the services you provide, and the designs you conceive.

How to Make a Value-Stream Map

Learn how to see the wastes that are holding you back by enrolling in LEI’s Learning to See Using Value-Stream Mapping, a go-at-your-own-pace, web-based workshop based on the innovative approach outlined in the landmark Learning to See Workbook.

The concept of sustainable development comes from the Brundtland Commission in 1987: “A development model that meets our present needs without compromising the needs of future generations.” (Moldan, Janouskova, & Hak, 2012). In sustainable development, there are three major elements: environmental aspect, social aspect and economic aspect. In the past, companies often gave priority to economic issues in performance management. However, according to the current trend, the economy and ecology have been facing a crisis. Especially due to the impact of the Covid-19 epidemic in recent years, many companies will therefore be restricted by epidemic prevention policies. Facing difficulties at the operational level, how should companies respond when faced with such difficulties? In order to respond to such challenges, many companies have begun to formulate innovative strategies, break the original strategies, adopt innovative models to change the original business model, and take all aspects of economic, social, and environmental factors into consideration to formulate innovative strategies for sustainable development. Strategies and business models to achieve corporate sustainable development goals.