How do lean masters create a pipeline for diverse leadership talent? That is the key question explored by Herman Miller veterans Jill Miller and Chris Shier in their upcoming session (A Structured Approach to Developing Lean Leaders) of the Virtual Lean Learning Experience kicking off on September 14. These two, and many others, have been working on this challenge for more than a decade at Herman Miller, a company that has systematically developed more than 350 group leaders and team leaders as a core element of the company’s management system.

As the date approaches, we are dipping into the LEI archives to select a handful of relevant archives sharing how HM and others have developed teams and individuals in a manner that produces outstanding leaders.

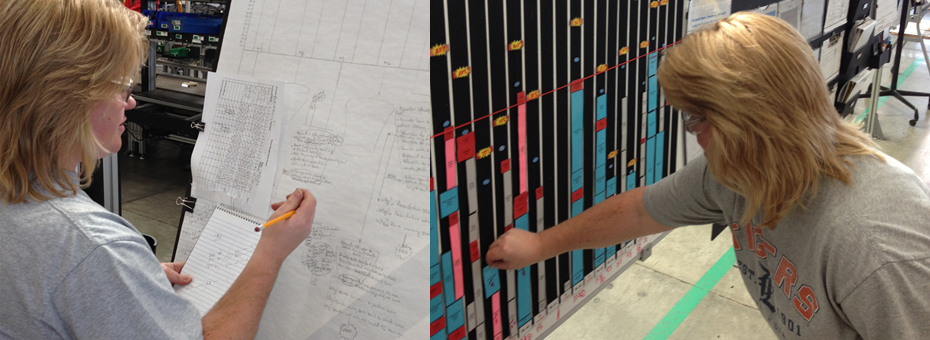

Perhaps one secret to Herman Miller’s ability to develop leaders is revealed in its clear focus on building a problem-solving culture. In this excellent interview with HM leaders George Mason and Dan Bos by Lex Schroeder, lean is presented as something that is discussed daily, which helps align workers from across the organization in shared learning. Lean and leadership are woven together at a basic level; and identifying one’s talent for teaching the soft skills of problem-solving as much as the known tools characterizes the overall program.

That said, John Shook reminds us that Herman Miller, like any great lean company, grounds its leadership practice in the gemba. “You cannot separate management, or leadership, from work, or the content of the value-creating work of the business,” he notes in his piece Encouraging Signs on Lean Leadership. “Lean starts (and eventually starts again) with the fundamentals of how you work at a micro-level detail,” he says. “You can’t, as many theorize, separate leadership in some abstract notion from that place of work.”

In that regard, the key to developing leaders through the daily process of tackling problems large and small is always focusing improvement work on specific, tangible challenges. According to Cleveland Clinic Medical Director of Continuous Improvement Lisa Yerian, people working on continuous improvement avoid vague requests for “support” or “buy-in” and instead aim to make very clear, specific asks.

In Stop Asking Your Leaders to “Support” Your Lean Transformation, Yerian notes that clarifying any commitment to change benefits from specifying what exactly needs improving—as well as articulating exactly how the leader will engage with the work (and worker) always improves the opportunity for progress. Finally, another basic principle is that “we don’t ask for anyone to ‘support’ something they haven’t yet had the opportunity to experience, understand, and critically evaluate.” This requires leaders to understand the gritty details of the situation and learn about the target condition that are necessary for building a culture of improvement.

Above all, learning to lead in a lean setting demands a personal shift by the individual, who must learn to move from putting out every fire and getting comfortable with learning to ask the best questions and patiently persist with problems so that they are helping others learn and grow. In Leading and Learning the Toyota Way, Tracey Richardson elaborates on this core idea powerfully:

“As a consultant/instructor, I still practice this type of thinking: leading and learning. Do I always have the right answers? No. Will I make mistakes? Of course. But my goal is always to study hard, listen, learn, and engage others. By doing this I practice my own cycles of continuous improvement myself so I can share my new wisdom immediately. As leaders, we must constantly find ways to teach and lead through our actions, not just our ideas. These actions should be in line with a PDCA-mindset that supports our business plan/true north. When this is our guiding principle, when we are genuinely willing to learn and engage alongside team members in service of our true north, we are building a culture where people truly are the organization’s most important asset.”