I received a lot of questions on-line and off about last week’s column on the pending closing of NUMMI. One question in particular came up a lot: “What did you really do to change the culture at NUMMI so dramatically so quickly?” It’s one thing to say at a high level, “We instituted the Toyota production and management systems.” It’s another to describe more specifically what we actually did that resulted in such a turnaround of the culture.

I’ll dive into that deeper topic this week in my usual way – describing what I learned and how I learned it. (By the way, that’s why I usually write these columns in the first person. We all have unconscious biases in how we perceive and report. Writing in first person helps you, the reader, to see and judge my biases for yourself. Thanks, Mike, for reminding me to point that out. Furthermore, I always try to make it obvious when I am providing facts versus interpretation or opinion.) And to do justice to this important topic, this column is much longer than your typical web blog. So, consider yourself warned.

I worked for Toyota, not NUMMI or GM, and was based at Toyota’s headquarters in Toyota City, working with NUMMI and GM people when they visited Japan, while visiting NUMMI itself periodically.

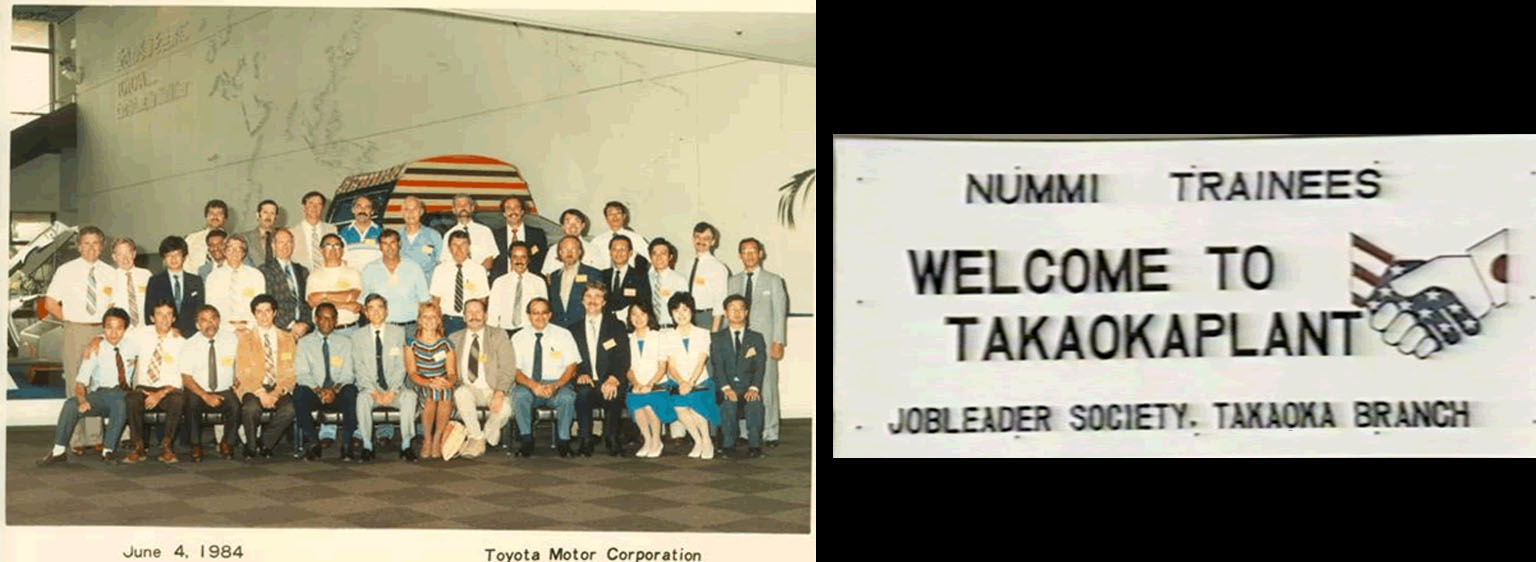

As it was for many others, NUMMI was an incredible learning opportunity for me personally. Before I could help Toyota teach GM or anyone else, they had to teach me first. So, starting in late 1983, Toyota put me to work at the headquarters and at the Takaoka Plant (shown above, as it was in 1984), NUMMI’s “mother plant” that produced the Corolla. I worked on all the major processes of a car assembly plant (as illustrated in the simple graphic below, which they used to orient me to what I was about to experience). Then, working with Japanese colleagues, I helped develop a training program to introduce the Toyota system to the American employees of NUMMI.

To recap briefly from last week, GM was looking for a few very tangible business objectives with NUMMI. It didn’t know how to make a small car profitably. NUMMI was also a chance to put an idle plant and workforce back to work. And, of perhaps lesser importance at the time, but still real, they had heard a little of Toyota’s production system (Len Ricard and a few others had looked closely at Isuzu, which had learned from Toyota). This would be a chance to see it up close and personal, a chance to learn.

On the other side of the fence, Toyota faced pressure to produce vehicles in the U.S. It was late bringing production to the U.S. Honda and Nissan were already building cars in Ohio and Tennessee, respectively. They could have just chosen to go it alone, which would have been quicker and simpler. But Toyota’s aim was to learn, and to learn quickly. What better way than to get started with an existing plant, and with partners helping them navigate unfamiliar waters?

The NUMMI Learning Opportunity for Toyota

At the time, the workforce in the old GM Fremont Plant was considered to be an extraordinarily “bad” one. Many considered it to be GM’s worst. The workforce in those days had a horrible reputation, frequently going out on strike – even wildcat strikes – filing grievance after grievance, and even sabotaging quality. Absenteeism routinely ran over 20%. And, oh yes, the plant had produced some of the worst quality in the GM system. And remember, this was the early 1980s. So to be the worst in GM’s system at that time meant you were very, very bad indeed.

So, Toyota had many concerns about transplanting perhaps the most important aspect of its production system – its way of cultivating employee involvement—in getting started. How could workers with such a bad reputation support us in building in quality? How would they support the concept and practice of teamwork?

As it turned out, the “militant” workforce was not a major obstacle. Many problems did crop up, but they were ultimately overcome. In fact, the union and workers didn’t just accept Toyota’s system, they embraced it with passion. We took the quality of the plant from GM’s very worst to GM’s very best – not just bad to good, from worst to best – in only one year. The exact same workers, including the old troublemakers. The only thing that changed was the system. The production and management system.

The Workforce

About 85% of NUMMI’s workers at start-up were UAW members from the old GM Fremont plant. Another 5% or 10% were from a Ford facility from just down the road in Milpitas that had also closed. A myth about NUMMI over the years has been that the old troublemakers from the GM days were weeded out. Even within GM, it is commonly believed that NUMMI’s new employee assessment process filtered out the radicals who had caused so much trouble in the old days. Not true. The old troublemakers, previous strike leaders, were still there. But, they weren’t troublemakers anymore. That absenteeism that regularly reached 20% or more? Immediately reduced to a steady 2%.

And check out this article from summer of 1985. The significant thing about it is the publication it appeared in – “Solidarity.”

Excuses, Excuses

From the beginning there have been those who try to explain away NUMMI’s success with excuses. “Well, the plant had been shut down and the workforce laid off, so of course they were motivated …” “NUMMI developed an elaborate assessment process that weeded out all the troublemakers. Only docile ‘team players’ were hired back.”

But, if being brought back to work after having been laid off is sufficient for successful turnaround, successful turnarounds must be happening every day. And, factually, it simply isn’t true that the old troublemakers were weeded out.

Others try to explain the early failure of GM to implement TPS to Toyota’s failure to bring over the best and latest technology of TPS. Toyota kept the best stuff – the secret sauce – behind locked doors.”

Well, I was inside the rooms when the doors were locked. And I can assure you that nothing was held back.

So, What Is Culture and How Did We Change It at NUMMI?

Once observers accept that idea that NUMMI was, no excuses, caveats, or qualifiers, a successful transformation, the question comes: “Okay, so, how did you change the culture? What did you do that changed such a troublesome workforce into an excellent one?”

It’s a great question.

It’s one thing to say the culture changed because we put in the TPS or changed the managers or management system, but it’s another to define exactly what really changed the culture.

The individual who put the concept of “corporate culture” on our collective radar screen was Professor Edgar Schein of MIT. And, interestingly, there is no one who is more skeptical than Schein about claims of easily making wholesale changes in corporate cultures. While Schein teaches that culture is hugely important, he also argues that you don’t change the culture by trying to directly change the culture.

I’ve long used a pyramid that I later found out was almost the same as Schein’s model. Trying to capture what I had learned of how the culture was changed at NUMMI, I developed this simple model:

The typical western approach to organizational change is to start at the bottom, change the culture by trying to get everyone to think the right way, so their values and attitudes will change and they will naturally start to do the right things. That’s represented by the left side arrow, running bottom to top.

What I learned was most powerful at NUMMI was to start with the behaviors, with what we do. Define the things we want to do, the ways we want to behave and want each other to behave, provide training, and then do what is necessary to reinforce those behaviors. The culture will change as a result. That’s the right side arrow, running top to bottom.

It’s easier to act your way to a new way of thinking than to think your way to a new way of acting.

John Shook

This is what is meant by, “It’s easier to act your way to a new way of thinking than to think your way to a new way of acting.”

Jose Ferro of the Lean Institute Brasil had studied with Schein as a grad student at MIT and, seeing my pyramid, said I had it slightly wrong. The entire pyramid is the culture; the base is your basic assumptions of how the world works. That made sense to me. It was only then that I learned that these ideas had been fully articulated by Schein long ago. (That was just one of the many times I have thought I had a bright new idea only to find out someone smarter had thought of it long ago.)

So Schein’s pyramid would look like this:

Schein himself describes culture as, “The pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.”

Maybe this definition from the Chambers dictionary is easier, “Culture: the state of being cultivated.”

So, the question now becomes: how is it that we changed the culture at NUMMI by changing the behavior?

The best example of how the culture was changed at NUMMI – there are others – is the famous stop-the-line andon system on the assembly line. (I’ll describe in detail in an upcoming column how my team leader would help me whenever I had problems completing my standardized work on the assembly line at Toyota’s Takaoka Plant in Japan.)All of the GM and NUMMI people who underwent training in Japan experienced learning and working with the stop-the-line system (or some variation of it). One of the decisions to be made in establishing production at the joint venture was whether or not to install the stop-the-line system. For Toyota, of course, that was no decision at all – it was a given. The andon system epitomizes Toyota’s focus, belief, investment, commitment to developing means to support employees in working in harmony with equipment and processes to build in quality.

The history of Toyota’s andon goes back to the group founder Sakichi Toyoda. Mostly through reengineering ideas he found from textile companies in the U.K. and the U.S., he developed an automatic loom that would stop itself whenever a thread would break. Moreover, he developed an auto shuttle change device that not only would change the shuttle on the fly (without stopping the loom, the most unique innovation on his loom – the other pieces existed in one form or another on other looms) it possessed a simple sensor that would detect that the thread was about to run out, and then change the shuttle before it ran out.

Further, he devised a simple andon apparatus that would pop up to notify the worker whenever a loom stopped for some reason. The combination of innovations enabled a single worker to monitor several dozen looms, resulting in a tremendous boost in productivity AND quality. And, critically, it established a way of people and machines to work together in a kind of “harmony,” with machines doing what they do best, supporting people to do what they do best (think) while building quality in at the source.

To this day, the principle and practice embodied in Sakichi’s old loom forms one of the pillars of Toyota’s way of working. (andon and stop-the-line are elements of one of the two pillars of the Toyota Production System – jidoka. For more on jidoka (and there is much more), refer to Chapter Three of Kaizen Express.

A cornerstone of Respect for People is the conviction that all employees have the right to be successful every time they do their job. Part of doing their job is finding problems and making improvements. If we as management want people to be successful, to find problems, and make improvements, we have the obligation to provide the means to do so.

If we as management want people to be successful, to find problems, and make improvements, we have the obligation to provide the means to do so.

But, some of our GM colleagues questioned the wisdom of trying to install andon at NUMMI. “You intend to give these workers the right to stop the line?” they asked. Toyota’s answer: “No, we intend to give them the obligation to stop whenever they find a problem.”

With standardized work, each worker on the assembly line knows precisely what his or her job is. He or she is given the knowledge and skills to know when he has encountered a problem (an abnormality that prevents him from successfully completing his SW), to know what to do when he’s found such a problem, and knows exactly what will happen when he notifies. His or her team leader will come to provide assistance within his job cycle.

That translates into a promise from management to the workforce. “Whenever you have a problem completing your standardized work, your team leader will come to your aid within your job cycle.” That’s quite a promise to a workforce of a couple thousand workers whose job cycle is in the neighborhood of one minute. But, Toyota learned that that is what it takes to enable workers to build in quality and to be engaged in problem-solving and making improvements.

How the NUMMI Way Was Different from the Old Way

That is what changed NUMMI’s culture. Given the opportunity – and challenge – to build in quality, the new-old NUMMI workforce could not have been more enthusiastic about the opportunity to show that they could build quality and well as any workforce in the world. Quality, support, ownership – these things were integrated within the design of each job.

Contrast that with my first experience observing work on a Big Three assembly line.

In early 1995 at an assembly plant on the outskirts of Detroit, I observed a worker make a major mistake. A regular automated process was down for the day so the worker was making do with a work-around. And with the work-around, he managed to attach the wrong part on a car. He quickly realized his mistake, but by then the car had already moved on, out of his work station. Then I saw an amazing thing.

There was nothing that the worker could easily do to correct his mistake! Scratch the word “easily” from that. There was NOTHING he could do. Far from the NUMMI/Toyota process of making it: (1) difficult to make a mistake to begin with, easy to do the job properly, (2) easy to identify a problem, to see when a mistake or other problem occurs, (3) easy and in the normal course of doing the work to notify his supervisor of the mistake/problem, and (4) comfortable with the knowledge of what would happen next, which is that the supervisor would quickly determine what to do about it.

But for the worker on the Big Three assembly line there was, practically speaking, NOTHING the worker could do about the mistake he had just made. No rope to pull. No team leader nearby to call. A red button was located about 30 paces away. He could walk over and push that button, which would immediately shut down the entire line. He would then indeed have a supervisor come to “help” him. But, he probably wouldn’t like the “help” he would get.

So, he did nothing. To this day, no one knows what happened there except that worker and me. (A good alternative would be to simply tag the vehicle with the problem, so it could be addressed later. Either that alternative wasn’t available to him or he didn’t know about it or he chose to not to exercise it.) But, the contrast with the NUMMI/Toyota process couldn’t have been more dramatic.

So, what changed the culture at NUMMI wasn’t abstract notions of “employee involvement” or “learning organization” or even “culture” at all. What changed the culture was giving employees the means by which they could successfully do their jobs. By communicating clearly what their jobs were and providing the training and tools to enable them to perform them successfully. The challenge to build in quality combined with provision of the enablers to successfully do so transformed the new-old NUMMI workforce from the worst to the best. The transformed workforce couldn’t wait to show the world that they could build quality as well as anyone.

The stop-the-line andon process is just one example but it is a good one for two reasons. First, it concerns directly with how people do their work RIGHT NOW. For each of us, every day, every moment, work comes at us. How are we equipped to respond? The andon system isn’t just a set of manuals and principles or training – it is how the work is done.

Secondly, on a practical level, the most important and difficult “cultural shift” that has to occur in a lean transformation revolves around the entire concept of problems. What is our attitude toward them? How do we think about them? What we do when we find them? What we do when someone finds one and exposes it? The andon process (and the entire pillar of jidoka) concerns building in quality through exposing problems. Sometimes those problems are of our own making.

That can be a very personal and threatening matter.

No Problem is Problem

Every person in a supervisory capacity, including hourly team leaders, visited Toyota City for two or more weeks of training at Takaoka plant. The training included long hours of lectures but most importantly practical on-the-job training in which they worked alongside their counterparts to learn what was to be their job back in California. At the end of each training tour, we asked the trainees what they would most want to take back with them to Fremont of all they had seen at Toyota. Their answer was invariably the same: “The ability to focus on solving problems without pointing fingers and looking to place the blame on someone. Here it’s ‘five whys.’ Back home, we’re used to the ‘five whos’.” Call attention to the problem to solve it, or to the behavior to change it, but not to the individual for being just “wrong.” (That’s not to say the Takaoka trainers weren’t hard on problems. They were. And if problems repeat or the same individual repeats the same mistake, individuals would be called out -loud and clear.)

“Problems” were indeed viewed completely differently. Americans like to respond “no problem” when asked how things are going. One phrase known and used with gusto by every early member of NUMMI was the Japanese word for “no problem,” which, when spoken with a typical American accent, sounded pretty much like “Monday night.” So when Japanese trainers tried to ask how certain problems were being handled, American NUMMI employees could be heard all over the plant cheerily shouting, “Monday night!” The response to this by the Japanese was, “No problem is problem.” There are always problems, or issues that require some kind of “countermeasure,” or better ways to accomplish a given task. And seeing those problems is the crux of the job of the manager.

The first case I know of a Toyota manager issuing the now-famous Japanese English edict of “No problem is problem!” was Mr. Uchikawa (who I also mentioned last week). As general manager of Production Control—arguably Toyota’s area of most unique operational expertise – Mr. Uchikawa had a team of six very smart, mid-level GM managers working for him. Being very smart, young GM managers, they had a ready response whenever Mr. Uchikawa would ask them to report on how things were proceeding – “No problem!” The last thing they wanted was their boss sticking his nose into their problems. Finally Mr. Uchikawa exploded, “No Problem is problem! Managers’ job is to see problems!”

The famous tools of the Toyota Production System are all designed around making it easy to see problems, easy to solve problems, to make it easy to learn from mistakes. Making it easy to learn from mistakes means changing our attitude toward them. THAT is the lean cultural shift.

But, Questions Remain

But, there are in fact some unanswered questions that remain despite NUMMI’s success. Questions about how a company, your company, could actually do this.

NUMMI was a mixed brownfield-greenfield venture. It occupied old buildings with an old workforce, but NUMMI was truly reborn, with a new name (the name “NUMMI” for New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. was supposed to sound cutely like “New Me”), bosses, operating system, and character. But, what happens when you enter into an ongoing operation that has its own ways of doing things, entrenched traditions, and perhaps unstable, even chaotic environment?

Training – everyone who supervised anyone at the start-up began their career at NUMMI with an experience in Toyota City, shadowing a mentor, seeing first-hand how Toyota does it, soaking up the culture, and learning their job, their role. In the first couple of years, about 600 NUMMI individuals – anyone who supervised anyone – visited Japan for at least two weeks of intensive training.

That was combined with around 400 three-month tours from Toyota trainers from Japan who would work side-by-side with their counterparts at NUMMI. That’s a huge investment that few think they can afford. Is it possible to have success without THAT much investment? And what if you don’t happen to have (as NUMMI did) access to a plant that was a model of lean production to learn from?

Product and process – all the physicals. Truth of the matter is, there was a world of difference between assembling an Olds Ciera and a Corolla. Compared to the products, the plant workers had been used to, the Chevy Nova practically assembled itself. Add the Toyota engineered processes, layouts and job routines, and a dramatic improvement in performance was virtually assured.

Management. I always point out, as I did above, that NUMMI’s workforce was the same workforce that had been there before. That is true. What I sometimes don’t have time to add is that, true the workers were the same, but the managers … all the managers were new. They may have been from GM, from Toyota or hired from the outside, but they were new to NUMMI.

And it’s the management process that really makes all those nicely engineered product and process designs really rock and roll.

The Management Question

If we look at GM’s continued struggles as well as some of Toyota’s more recent struggles, we have to recognize that there are many questions about management that remain unanswered.

I left Toyota in 1994. At that time, GM still had not learned to make a small car profitably. And they still had not “learned” the Toyota Production System. Many GM individuals had learned the TPS quite well, but GM as an institution still didn’t know what to do with it. It would be the late ’90s before they started making headway.

The first GM people who went back were quickly swallowed up by the GM system. They knew they needed to be placed together, as a group, to have an impact, but for the most part they were scattered around. But GM kept sending people and people kept learning. By the late ’80s, NUMMI grads had created a GM version of Toyota’s system – they called it Synchronous Production – and were providing training to people in large numbers. In the ’90s, GM decided to get serious and put the full system in place. Deciding it was too difficult to make progress in the U.S., they went first to Europe, then to Latin America, and, after they felt they really knew what they were doing, finally here in the U.S. Today GM has plants that arguably are on a rough par with Toyota in terms of both quality and productivity. World class.

Stepping back, it took GM close to 20 years to make serious visible progress with its lean learning (that’s just me talking – my GM friends may differ with that assessment, but it certainly took at least 10 or 15 years). Maybe that’s about how long it takes. A lot of the progress was made possible by sheer attrition and critical mass. As more and more people learned at NUMMI while more and more old timers retired, eventually the tables turned. A tipping point.

There are still serious questions about GM’s success in fully absorbing all of the lessons of NUMMI. The first of those revolves around people and management. Are people engaged, at all levels, in exposing problems and making improvements? Are managers engaged in developing subordinates and encouraging ideas from them? Are the new, world-class GM plants continuing improving and adapting or just running them in accordance with their nice new design? There is no steady state, so things are either improving or declining. Which is it? How GM is embracing the people side of lean holds the key to how these questions will be answered.

The second revolves around another aspect of the role of management, setting and managing to a vision or sense of purpose that can guide the organization for the longer term. Deming called it constancy of purpose. Its opposite is the ruination of all change efforts, POM, program of the month. Can there be any doubt that keeping both eyes on Wall Street’s 90 day evaluations -90 day evaluations for an industry that runs on rhythms of more like four years – is one reason for Detroit’s decline? And it is no coincidence that most of Detroit’s – and almost ALL of GM’s – CEOs have been finance people. You can’t run a global auto company based on short-term Return on Investment calculations. I have the highest hopes for the future of the New GM, but I must say it was a disappointment when every single person Obama appointed to the Auto Task Force was a finance person who knew nothing about the auto industry. And now, GM’s new chairman is a telephone guy? His first observations as reported in the press could have come verbatim out of Roger Smith’s playbook from the early ’80s. He’s seen the problem: GM needs “strong product-line managers.” Good luck New GM.

Purpose, Process, People

In a column last December, “Survive to Make Money or Make Money to Survive?” I used LEI’s Purpose, process, and People framework to examine GM’s learning from NUMMI. Contrary to popular opinion, GM learned a LOT from NUMMI/Toyota about process, with success in that regard that is far more than most observers realize. Their plants are now world-class in quality and productivity. But, I’ll suggest that GM never got far enough into the people part. Remember the sight last year in Washington of the chairman of the UAW sitting side-by-side with CEOs of the Detroit Three? Too bad they didn’t try working closely together like that many, many years ago.

Perhaps most importantly, could it be that GM’s sense of its very purpose has been utterly different from Toyota’s? The question of “What are we here for?” is an important one for an organization, and one that receives remarkably inadequate attention. I suggest that the difference in purpose between GM and Toyota can be summed up simply: Are we here to survive to make money or make money to survive?

Both Toyota and GM want to make money. Of course. And both want to survive. But, the distinction between a corporate purpose of survive to make money versus make money to survive is a difference that makes a big difference. And, if learning is the right measuring stick to judge the impact of NUMMI, it just may be that purpose isn’t really something you simply learn.

john

John Shook, Senior Advisor

Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc.