Dear Gemba Coach,

My management is asking for an assessment of our lean progress. How should I do this?

Tricky problem. I’m not sure there’s any real way of assessing lean progress, although most corporate programs will try at some point or other. About 20 years ago, my father was one of the first to develop “roadmaps” for lean. These resources identified dimensions for lean progress, such as quality or just-in-time. They settled on five levels and then did a mammoth job of identifying which exact practice should reflect, say, level four on just-in-time. I’ve still got the original roadmaps somewhere and they spawned an entire consulting industry of implementing lean by following the level-by-level applications of all the tools and practices. In the end, it turned out that although the roadmaps were useful to clarify what the company was learning with Toyota’s tutelage at the time, they were a poor guide to lean progress. Since then, I’ve seen many “roadmap” driven programs which keep lots of people very busy, but without much to show for it.

Management loves roadmaps and assessments because these exercises are very reassuring. They show where we want to be, where we are, and the milestones to get there. This plays into what management does: find the solution and execute. And yet … we’ve learned (often quite painfully) over the years that lean is a learning system, not a management method: you train and develop people, and as they become better at what they do, performance improves. There is a dotted line (as opposed to a straight one) between managerial action (training and developing) and results. And while the results are actually greater and quicker than by the traditional management direct action approach, many executives are profoundly uneasy with the model of training and trusting as opposed to directing and controlling. This is a very old story and not about to change any time soon. As a result, I don’t believe there’s any way of assessing lean level or lean progress in pure learning terms, which is always tricky. What we can assess though are (1) financial results, (2) performance progress and (3) lean efforts.

Get Physical

Here’s the most important thought regarding this: ultimately, the aim is not to implement lean but to become lean. And this should appear on the P&L in terms of increased sales, better cash flow, increased profitability and lower relative capital expenditure. If you’re not aiming for significant results at this level, you’re probably doing something fine such as operational excellence, six sigma, or world-class manufacturing, but it won’t be lean. In Art Byrne and Orry Fiume’s terms: lean is a business strategy, not a manufacturing tactic. If that point is missed at the outset, you can evaluate progress all you want, you’re unlikely to transform your company’s position on its markets.

As Orry also points out, financials are nothing more than a price multiplied by a physical quantity, or a cost multiplied by a physical quantity. They are indicators based on actual performance and are subject to all forms of adjustments. Which means that improving the financials starting at the P&L makes about as much sense as trying to accelerate your car by turning the speedometer needle. If you want better results, you need to improve physical performance.

And physical performance is relatively easy to assess. On a monthly basis you can track specific physical indicators that reveal whether you’re better, equal to, or worse than you were at a fixed point (say end of year figure last year):

|

Indicator |

End of Y-1 |

Current month |

Better |

Same |

Worse |

|

Accidents |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

OTD |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

Customer complaints |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

Internal ppms |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

Days of inventory |

|

|

? |

|

|

|

PPH |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

Suggestions |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

Absenteeism |

|

|

|

|

? |

There is no direct one-to-one relationship between any one indicator and the P&L. But by examining the financial numbers and then studying your performance indicators, and seeing how they correspond, you’ll build an understanding of what goes on in the company and how relatively well you’re doing site to site.

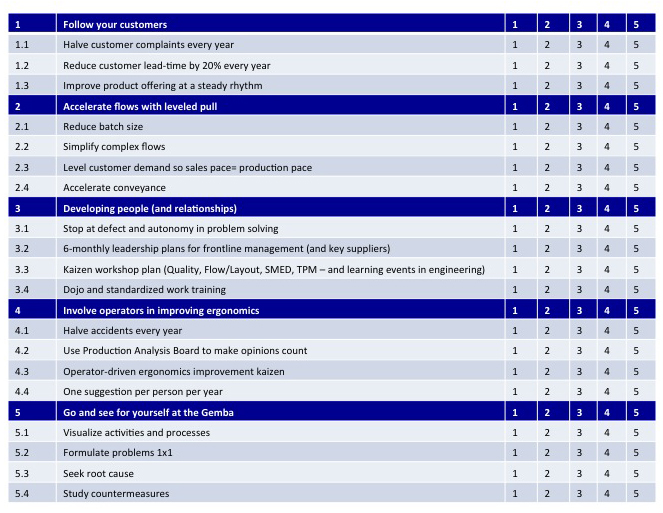

Which brings us to the third part of the assessment: how hard are we working to obtain these results? I’ve just come across this issue in a company that was recently purchased (partly because of its spectacular lean results under the previous CEO). The new owners have a very traditional cost-reduction “lean” program based on the usual mish-mash of spot kaizen workshops and the purchased management team is scratching its collective head to figure out a way to explain what they’re doing, how they previously had results, and why the new system is not delivering. For what it’s worth, we’re come up with five dimensions of effort:

- Following our customers: how hard we try to satisfy customers now by solving their usage problems and develop new offerings that do so better

- Accelerating flows: essentially about reducing lead-time end-to-end

- Developing people: specifically by stopping at defect and solving problems rather than working around issues (this includes working with suppliers)

- People involvement: what efforts do we make to involve employees in improving their own workplaces

- Gemba focus: how much time do we spend at the workplace to go and see, get people to agree on their problems, train and think deeply about our issues

I’m not claiming this is universal—it’s simply what one company came up with. It’s worked well for them—and in fact they’ve been using it with their suppliers. On each of these dimensions we self-assess effort on a one-to-five scale: for no effort at all to main effort. This is the assessment grid we came up with:

The list is clearly not exhaustive, and should be thought widely as applying to, say, engineering teams and suppliers as well as to production. I accept that it’s kind of silly to even try to reduce lean to one page, but one good point of this assessment is that it reflects the system nature of lean: if you draw a radar chart of your score you’ll soon see how balanced your vision of lean is and we all know by now that focusing on one aspect and ignoring all others simply does not pay.

Assess Learning

I’m not fonder of assessments than I was before. I still believe these are dangerous tools that can become bureaucratic exercises that can get in the way of deep thinking; and they can lead one to become grade-focused and miss the point of learning altogether. On the other hand, one-to-five self-assessments of efforts can produce tangible benefits to managers trying to clarify their overall lean work. This grid might help you reflect on how hard you’re trying. Be warned: this was conceived as a self-assessment, not a third party audit.

Personally, I try to assess learning: what do we understand now that we didn’t before. But I’m fully aware this is too subjective for management. Still, the question remains, lean’s aim is to develop deeper understanding, which in turn, generates better results. I don’t know whether this will help but these are my personal guidelines to evaluate thinking progress:

DATA + CONTEXT = FACT

FACT + UNDERSTANDING = KNOWLEDGE

KNOWLEDGE + RESPECT = WISDOM

Ultimately, results are obtained more by solving the right problems than by solving problems right. The tricky part of lean is that the right problems tend to be the most difficult (or where we know the least), so we rarely solve them well (which terrifies traditional managers), but, on the other hand, as we doggedly keep on trying (and often failing), the situation changes and the company improves radically. In the end, I can’t think of any assessment that evaluates whether you’re focusing on the right problems other than spending time with a sensei at the gemba.