It’s one thing for a design team to understand its work using value-stream mapping and an obeya so it can complete tasks and deliverables on time. But very often, that’s not enough. Another variable — decision-making — can gum up the works, derailing even project teams adept at using the lean product and process development (LPPD) process to ensure collaboration and on-time project completion.

As a veteran LPPD coach, I’ve seen and helped design teams at other LEI LPPD Co-Learning Partners (CLPs) address this problem. In our collaborations, we developed a practice called Decision-Flow Mapping, a way to help teams better define and make visible the critical decisions and questions that would need to be made and answered to meet their projects’ goals.

GE Appliances, a Haier company, is one of those CLPs. This story describes how its next-generation dishwasher team applied the decision-flow mapping practice, the benefits it yielded, and what the team learned from the experience. The project, an $80-million investment at the company’s headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky, was the first program launched during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Improving Continuously

GE Appliances has been applying lean principles and practices for nearly a decade. As its journey continues, the company has recognized that creating value and improving value streams is best accomplished when starting new product development programs.

Over the past few years, the company’s new product development teams, guided by LEI coaches and the LEI LPPD Learning Group members, have experimented with and rolled out several LPPD practices to improve their teams’ performance. In particular, they found that obeya increased transparency by making their work visible and facilitated cross-functional engagement.

However, while the obeya helped them manage tasks and see issues, some project leaders believed that they could — and should — improve their work’s sequencing and synchronization, which, in turn, would accelerate learning and program completion.

Identifying a Problem

In reflecting on previous projects, the next-generation dishwasher team realized that they typically set up project tasks and timing in their obeya based on the estimated scope and previous project timelines. Yet each project has different challenges, so what needs to be learned and decided is also unique — so merely completing tasks on time does not always equal progress or guarantee success.

Moreover, sometimes they felt they were exerting more effort than needed, not so much in finishing a particular task, but when working through getting alignment and approval from their stakeholders to proceed. Stakeholders sometimes asked for additional information or were waiting on other people’s work to be done before making their decision, which led to extra unplanned work and/or program delays surfacing at the last minute.

Applying a Countermeasure

To address the issue, the team decided to map and track when and where they would need responses to critical decisions as they completed the project. The resulting decision-flow map helped the dishwasher team:

- Provide better visibility of when they needed a decision on a particular design element.

- Understand the dependencies between the decisions made by different teams.

- Define upfront the necessary knowledge and specific tasks required to make critical decisions.

- Help prioritize tasks to close the knowledge gaps.

- Drive decision-making to the people closest to the data.

- Understand whether they were on or off track in the project schedule.

- Create a cadenced forum for making and communicating timely decisions.

Defining the Decision Flow and Making it Visual

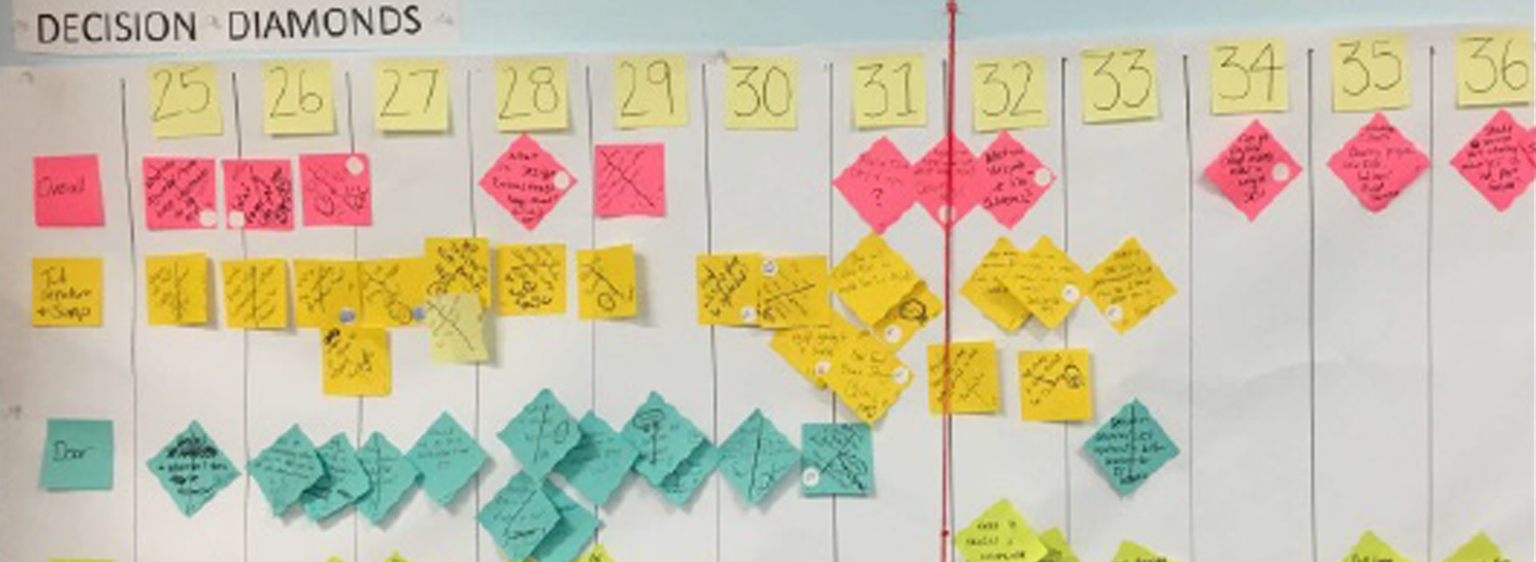

Alison Seward, the program director of the next-generation dishwasher program, organized the project team members into “fishbone” sub-teams. These teams mirrored the manufacturing process for the dishwasher (e.g., door, rack) and included cross-functional representation (engineering, operations, supply chain, quality).To set up the decision-flow map, the fishbone teams started by stepping back and asking themselves, “What are the fundamental decisions that need to be made on the project?” and “What key questions need to be answered to deliver customer value and achieve their project goals?”

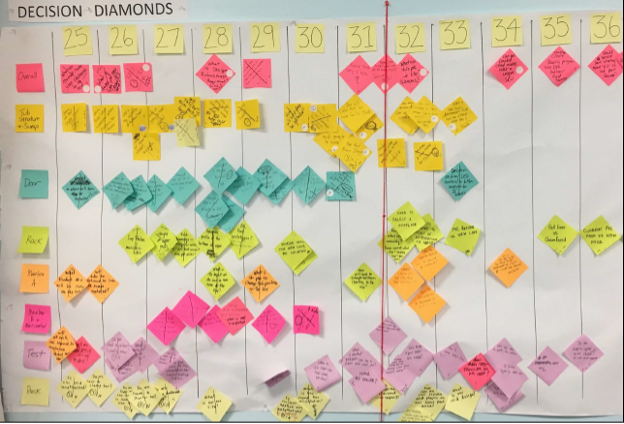

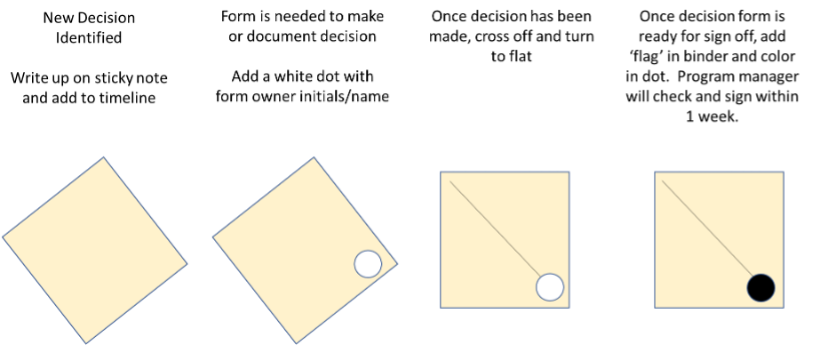

The team posted the decision-flow map prominently in the obeya so everyone could see progress and identify and prioritize decisions they’d need in the coming weeks. The team also defined visuals to clearly show the status of each decision (see below).

Meet and learn from Alison at the Lean Summit 2023 on March 8 & 9, 2023, in Tucson, Arizona. In a 90-minute learning session, she’ll share what she’s learned from her and her teams’ lean product and process development journey.

Managing the Decisions to Drive Flow

Setting up the decision flow and making it visual was only the beginning. Next, the team needed to execute and adjust the plan as knowledge gaps were closed and decisions made. So, as they neared each decision deadline, the team worked through the knowledge gap(s) that blocked them from making it. In some cases, it was clear what work they needed to do to analyze the situation and then use that data to make the appropriate decision. In the other cases, when the decision path was unclear or many options were possible, the team applied A3 thinking.

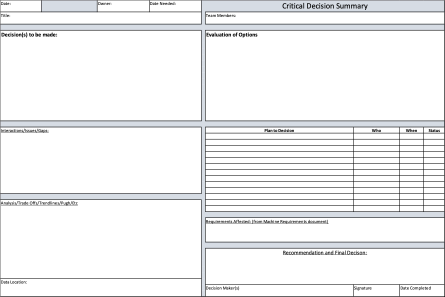

To make these more complex decisions, the project team formed a small group and worked together using a “Critical Decision A3.” Following the A3 process, the group worked through its knowledge gaps, showed its analyses, reviewed its options, and aligned to make the most informed decision.

Also, they met periodically with the program leadership to:

- Share the knowledge gained from the completed tasks.

- Evaluate their learnings and either decide as a team with the knowledge obtained or agree on the next steps needed to gain the information required to make decisions in the future.

The “Decision A3” also enabled teams to capture new learnings they could share with others or use for future projects.

Establishing a Decision-Flow Cadence

The development team incorporated a review of the decision-flow map into its obeya process. Every Friday, they reviewed it with the dishwasher core team, which included the program director and the fishbone leads. Decision owners shared the decisions made that week, and the group discussed any overdue/late decisions to analyze their impacts on the fishbone teams and the overall program. So, the Friday meeting ensured everyone was on the same page regarding decisions and provided a forum for any team member to ask questions or voice their concerns about decisions made that week.

“If fishbone team A is two weeks behind, it gives team B a chance to speak up and say, ‘My decision is now going to be delayed if you are not able to make your decision,'” Seward explains. “So it gets [the issue] in front of the entire team, so the 50-plus people in that session and everybody has the freedom to speak up and talk about those delays or decisions — what impact that may have on other groups.

The decision-flow map was an excellent complement to the other obeys tools they were already using, such as the visual schedule and the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) issue-resolution wall on which they recorded, tracked, and resolved problems. There was a great rhythm and flow between the three elements. For example, to call attention to an issue or problem, someone described it on a PDCA card. In reviewing that card, the affected sub-team identified two possible solutions, creating a decision.

Sometimes, the teams could work through that decision themselves without escalating it. However, they would add it to the decision-flow map if it had impacts outside their fishbone team or could impact the higher project deliverables (cost, schedule, etc.). Once the team made a decision, there were frequently “to do” items to execute it, and then they would track those to-dos on the visual schedule board along with all the other project tasks.

Getting Team Engagement

While the decision-flow map is a straightforward concept, Seward knew it would take some effort to incorporate it into the program’s existing operating system. Like many LPPD tools, using the decision-flow map may seem obvious and intuitive because new members can easily understand and use it. Still, the project leadership team must train and coach members on using it to gain maximum benefit.

The dishwasher team first trained the project core team (the program leadership team comprised of the leaders of each fishbone team) in the decision-flow mapping process, and they worked together to mold and modify it to fit the specific needs of their project. Then, these half-dozen trained leaders became well-versed in the purpose and methods of the decision-flow process. Finally, they shared that knowledge and guided its use across all dishwasher projects. It has now become part of the standard way they run all projects in the dishwasher organization.

Reflecting on Decision-Flow Mapping

Overall, the dishwasher development team agrees that adding the decision-flow mapping process to its obeya was an effective way to achieve alignment on identifying critical decisions and the knowledge needed to make them. In addition, by making the decisions visual and the decision-making process more transparent, everyone felt more confident they were working on the right task. Finally, and perhaps more crucial, by adopting this process, the team experienced fewer surprises and misunderstandings that typically would have led to rework.

“This is hands down my favorite obeya tool. I find that these types of simple, easy to understand, and easy to apply tools are the best assets for new product development,” Seward says. “This is a very empowering tool for the team to highlight areas where they are waiting on input to make a sound decision before moving forward to continue their work.” Also, she adds, “The decision flow did not fall solely on me as program director to guide the team through the process, which is a good thing as any process that relies on a single person to be successful is doomed to fail.”

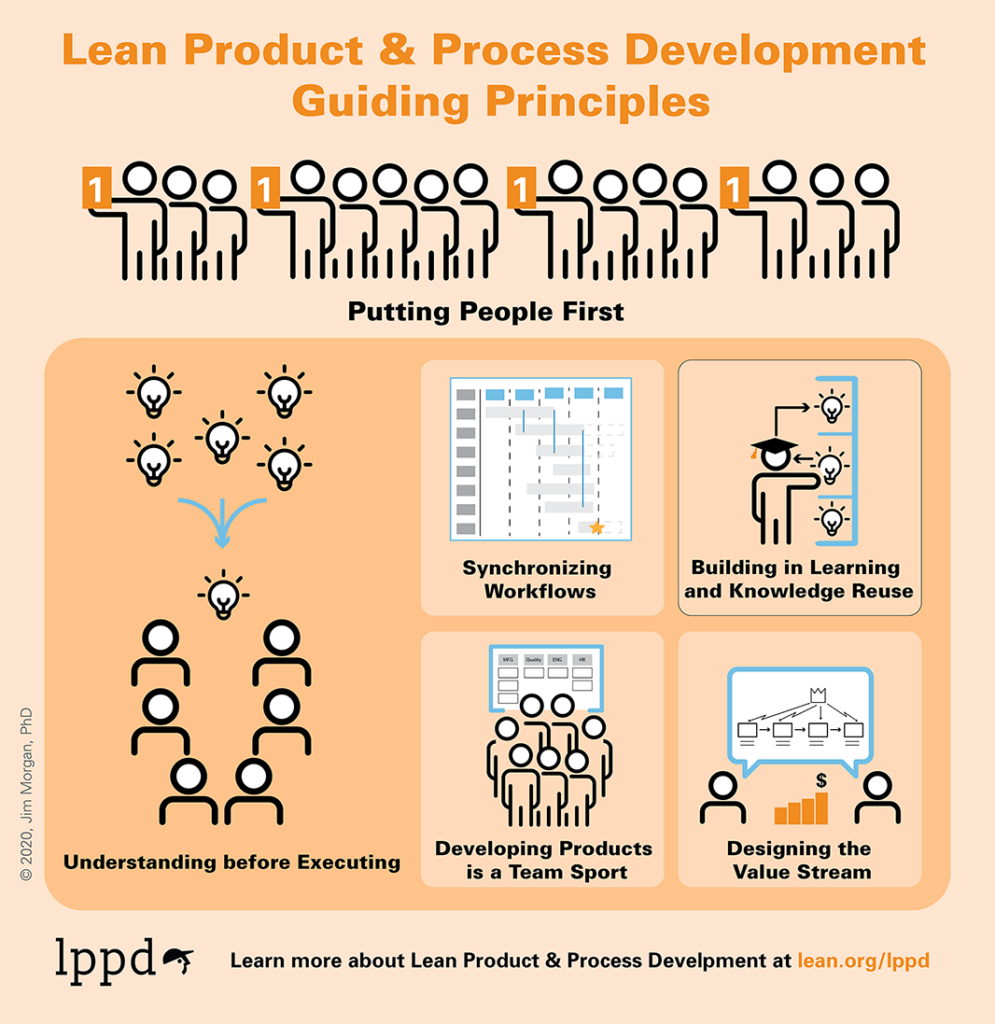

Understanding the LPPD Principles

From the perspective of those of us who work to advance LPPD thinking and practices and develop new, decision-flow mapping is another critical way to follow the LPPD guiding principle of Understanding Before Executing. This principle recognizes and highlights the problems that arise when project teams rush to get started and “make progress” on meeting their deadlines. Too often, this flurry of activity results in them expending time and effort brainstorming and closing knowledge gaps that may or may not be value added to the project.

So, the Understanding Before Executing principle reminds us to take the time upfront to study what’s needed to achieve project goals. And knowing what decisions we need to make is a significant part of that.

Decision-flow mapping also highlights another LPPD principle, Developing Products is a Team Sport, by addressing the need to keep all stakeholders informed throughout the development process.

Assuring the Adoption of New Practices

Finally, the team and I also reflected on lessons we learned about successfully implementing the decision-flow mapping process. We noted three critical implementation practices:

- The process was not imposed but introduced to solve a particular challenge.

- Before introducing the new practice, the program director and the fishbone-team leads first took the time to be trained and experiment with applying the method to see if it had the potential to help.

- The leads then taught and coached their teams on the practice and encouraged them to provide feedback to adapt the process to make it work better for them.

As Alison noted, one of the keys to successfully adopting the decision-flow mapping process was that it helped make team members’ work easier. It was and felt like help!

John – great article!! Large projects can end up with many loose ends and you shared a great way to manage the closure of the decisions that need to be made.