Of all the lessons Toyota has taught us, one that is seldom discussed, but I experienced personally, is how the company achieves a planning process that is so much more effective than traditional approaches used by North American companies.

When I worked there, Toyota leaders and managers did not plan by assigning objectives or tasks. They planned by assigning the responsibility to think. By that, I mean they planned by delegating the thinking responsibility, not just objectives, from level to level—from strategy and objectives to goals and tactics, and goals and tactics to targets and action plans. And generally, the planning tools they used were cascading A3s and cascading plans. A department head created an A3 explaining department strategy and assigning goals to the department head and managers to achieve individually and together to support the strategy.

This strategic planning process was very different from what I had experienced at North American companies. There, the process usually involved assigning unit managers objectives (now KPIs) that specify how the leaders expected the managers to contribute to the department head’s objectives–primarily financial. At Toyota, department heads deployed responsibility to unit managers for achieving specific performance improvement and capability development outcomes (goals) to help achieve the department’s strategic objectives.

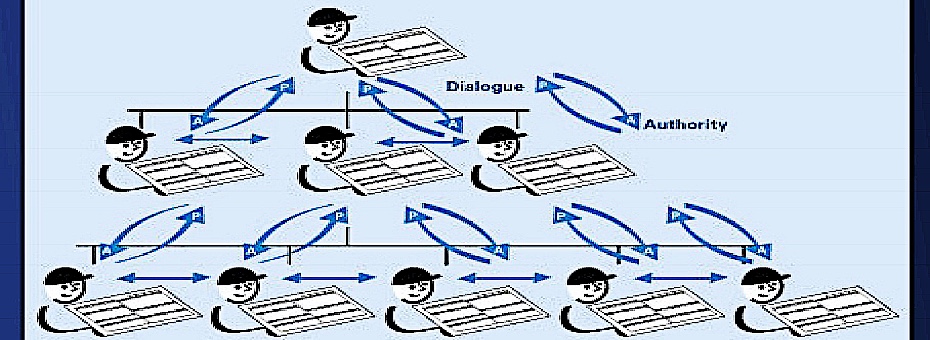

The crucial point is that, at Toyota, one level delegated responsibility to the next level to achieve certain ends while at the same time giving them the responsibility for thinking about and proposing the means. That’s why the A3s describing the purpose and thinking behind the upper level’s strategy and goals were necessary. The department head then assured alignment and coordination between the strategy and each manager’s plans through a back-and-forth discussion process called “catchball.”

Like most of you who work in North American companies, I was more accustomed to being told what to do and when to do it. Toyota’s planning approach forced me to think in ways I had not before.

Deciding Not Only How But Also What

The first significant difference was that I had to think about what I needed to get done, not just how to do what I was told to do. The process involved answering questions such as:

- What’s the purpose of my boss’s strategy?

- What’s the purpose of my unit, and what role should it take in supporting the strategy?

- What are the other unit managers planning?

- What does the business need from my unit’s specific function?

- What’s my unit’s current capability, and how do we need to develop it for now and the future?

This thinking is the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust problem-solving thinking that starts with a gap analysis.

- Where are we now in terms of our performance capabilities?

- Where do we need to be to contribute as necessary to the company and department?

- What are the significant differences and changes that we need to make so we can perform as required?

The questions didn’t end! My responsibility was to figure out, with my staff, how to answer those questions and close the gaps between where we were and where we needed to be over the planning year. By answering the questions, my staff and I created a plan for the year that mapped out a series of operational and organizational (primarily people and process capability) development initiatives. Our purpose was to think and plan how we could contribute to the department strategy and the business’ strategic aims and success by achieving the performance improvement outcomes we were responsible for that year.

How Planning Content Differs

The differences between Toyota’s planning approach and the typical North American company planning do not end there; they included what was considered in creating it (content) and the process (thinking) to create it. First, the specific content that Toyota considered and generally included in the plans, as I recall, had the following:

Goals and Target: Improve what, why, by how much, and by when? That is, a goal is not an action; it is an accomplishment.

Roles and Responsibilities: Who will be responsible for leading, doing, supporting, and reviewing what, when, and how?

Execution Process: Create action plans for each goal, alignment of action plans in a Master Schedule, visual tracking board/center, the anticipation of obstacles and issues, and plans for contingencies.

Management Process: Determine a process to review the schedule: Who will lead the plan-versus-actual Project Reviews and Gap Problem-Solving? Who will do work-site checks and lead the project team’s meeting? Who will report what, when, and how on the tracking board?

Change Leadership: Who will plan and lead the organizational communication processes, make the schedule, facilitate cross-functional and team coordination meetings, and prepare leadership and employee status reports?

How the Planning Process (Thinking) Differs

At Toyota:

- A plan is an agreement by those developing it and taking roles in it. A plan without that agreement is not a plan because it is not a commitment to follow through as described. Those agreeing to responsibility in a plan demonstrate their commitment by adding their initials next to their names.

- Implementing countermeasures involves more than making technical and workflow changes in a process or procedure. It also affects the people doing the work because it will change their work and work situation. The social aspects of creating a plan (participation, discussion, clarity of roles and responsibility, and communication) are as critical if not more than changing the organization and flow of the operation. Involving the people who will carry out the plan to create the plan is essential to success; it ensures they will follow through with executing and then sustaining the improvements.

- Change leadership activities during execution are planned and shown as separate processes, with their own Gantt scheduling lines, goals, and a flow of discrete deliverables, including communication, cross-functional sessions, and training. Successful planning and execution depend on relationships to help work through the rough spots and sort out unanticipated issues.

- The progression of actions to implement a change is planned as a sequence of action steps that result in handoffs of deliverables from one processing activity to the next, like the flow in a value stream.

- Targets for the flow of execution steps in individual action plans specify not just expected timing but also in-process indicators of what will be in place or delivered due to each activity in the process.

- Plan versus actual reviews are scheduled at the anticipated end of major phases in action plans. Timing is checked and impact assessed, and problem-solving activities to address gaps are initiated immediately (rather than promises to catch up). These are action plan team reviews and do not require management involvement unless there are significant issues.

- Teams reporting at these reviews are expected to come prepared to explain plan-versus-actual differences and how they are being addressed. Red-Green-Yellow status reports do not provide the information management needs to know to check and understand the reasons for the gaps.

- The master schedule for implementing a countermeasure also includes timing and targets for outcome or deliverables. Reviews are scheduled at major transition points in the execution plan, and responsibilities for review and reports are indicated in the plan. The purpose of these reviews is the coordination, communication, and assessment of overall change progress status and not problem-solving. General status summaries such as Red-Yellow-Green are not presented in the reviews.

- In planning, as in problem-solving, Toyota takes little for granted. It wants the facts that can be obtained and not assumptions. A saying in the company that illustrates is thinking is, “Planning is absolutely critical. Things never go according to plan.” Plans go through a form of Pre-Failure Mode Analysis, and leaders include contingencies in the master plan. In deciding where to locate its first North American plant, for example, Toyota had three full sets of plans for each of the sites it was discussing with the states where they were considering locating.

Looking at a study done in the 1990s on planning practices in Japan compared to North American planning practices, one thing that stood out to me was the significant difference in the overall effort spent. In North America, an average of 30% of a project’s timeline went into planning, and the remaining 70% was for execution. In Japan, the opposite was true. Japanese companies typically spent 70% of a project in planning and 30% on execution.

Another example of this difference is the startup of GM’s Saturn plant in Tennessee compared to Toyota’s planning process for selecting and building its plant in Kentucky. The Saturn plant was announced a year before Toyota announced its plant in Kentucky. Still, the Toyota plant started producing vehicles a year before the Saturn plant went into production. It took GM nearly two years to plan and complete construction and reach agreements with its suppliers and unions.

How was this large difference possible? How could Japanese companies accomplish so much more with so much less effort?

At least from what I have seen in North America, one reason may be that we tend to create a plan in isolation. We then announce it and spend a lot of our effort in execution explaining what we want to do and why, responding to objections, dealing with conflicts, and trying to get alignment so we can proceed in the first place. At Toyota, the opposite was the case. Planning was a process of building agreement and alignment as you developed a plan. To me, perhaps more than anything else, this is what makes all the difference.

Develop your structured problem-solving and leadership skills using A3 thinking: Manageing to Learn Remotely

Join David Verble for a 7-week learning experience and learn how to use the A3 methodology to solve important business problems.

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.