(Ah, another stroll down memory lane. In January 1995 I wrote the following article for AME’s Target magazine describing Wiremold’s experience with lean. We have received permission from AME to reproduce this piece on the LEI Post. Dates and other references have not been changed from the original publication. I hope you enjoy it.)

Three years ago, The Wiremold Company was an old-line, unionized, manufacturing company. We used traditional batch manufacturing processes, which were organized by function, to make our wire management systems.

At the old Wiremold, a product might take as much as six weeks to make its way from raw material to finished product. We’d make huge quantities of a single component because our . changeovers took so long. Often a batch of components would sit gathering dust in our large WIP inventory areas before products could be assembled because the other parts weren’t scheduled to be run that week. Finished goods were sent to our 70,000-square-foot warehouse down the road to wait until needed for shipping to a customer. We were cash poor, yet had such large in-process and finished goods inventories that we were shopping for more warehouse space.

In just three years, our sales have doubled and our profits have tripled

We’ve come a long way since then, reinventing ourselves into a vibrant, growing firm. In just three years, our sales have doubled and our profits have tripled. We’ve grown our base business by more than 50 percent, and supplemented that internally-generated growth with six acquisitions—five of which we were able to make without borrowing because we had freed up so much cash from inventory reductions.

Our success is not the result of any complex business strategy. Nor is it the fruit of some intensive program of capital investment.

Rather, we turned our company around by turning our manufacturing operation on its head: We adopted kaizen.

Our Results So Far

While the Wiremold experience is certainly not unique, I think the speed with which we’ve changed the culture of our organization and generated results is encouraging. We still have a long way to go, but our initial success provides us all with positive momentum.

We began to implement our kaizen program of continuous improvement in late 1991. In slightly less than three years, here are some of the changes we’ve made:

- Productivity has improved 20 percent in each of the last two years.

- Throughput time on products has dropped from 4-6 weeks to 2 days or less.

- The defect rate on our products fell by 42 percent in 1993, and by 50 percent in the first half of 1994.

- Inventories have been slashed by 80 percent, resulting in our space needs being cut in half.

- Profit sharing payouts for our employees have more than tripled.

- Equipment changeovers have been reduced dramatically—in some cases from as much ten hours to less than ten minutes.

- New product development time has been slashed from almost three years to under six months.

- Vendors have been cut from more than 400 to fewer than 100.

And these quantifiable results don’t begin to reflect things like the improvement we’ve seen in the most important areas—like employee attitude.

Getting here wasn’t easy. And sustaining our progress is just as tough. But we’ve learned a few things along the way about what works—and what doesn’t—that we’re glad to share with others.

Integral to Business Strategy

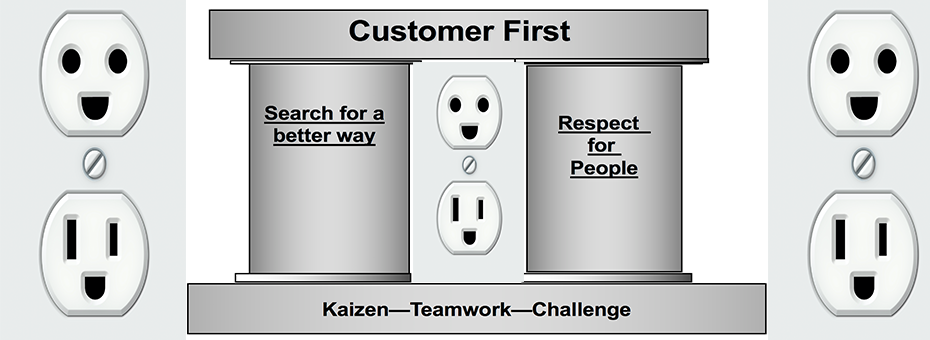

One ingredient essential to our success has been the way we look at kaizen. At Wiremold, we believe it’s a fundamental part of our business strategy. After all, our business delivery systems are what the customer sees.

If we fall behind in quality or on leadtimes, we disappoint our customer and we won’t succeed no matter how good our strategy. On the other hand, if our systems can outperform the competition, then we can outrun them.

We’ve actually made kaizen part of our business strategy: to continually “fix” our base business. We believe that the minute we stop doing so, we’ll fall behind.

Getting Started

As an outsider joining Wiremold in late 1991, I realized that we needed to make some fundamental changes in the way we manufactured our products. Something that I had learned by observing other change programs is that it has to be an “all or nothing” proposition. It just won’t work unless you make a significant commitment in time and resources and unless you take some risks. It also won’t work unless that commitment comes from the top.

So, one of first things that we did was to completely reorganize our operations.

Kaizen is a fundamental part of our business strategy.

Historically, our plants had been organized by function—milling here, presses there, assembly in another building, and so on. We began our improvement efforts by completely reorganizing our manufacturing operation into six independent product families and four support teams (tooling and maintenance, administration, shipping and customer service, and the JIT promotion office.) We realigned people and relocated equipment so that each team would have all of the resources necessary to make its product or provide its service.

For example, making our Tele-Power Pole product requires a number of resources such as rolling mills, punch presses, painting equipment, and assembly. Historically, each was in a different functional department. The departments were separated by large distances and run by multiple managers. In effect, no person or team was responsible for making the product—only some portion of it.

Our first step was to bring all the necessary equipment together in one area of the plant to create a discrete operating unit. Then we identified a team leader and assigned a team of four salaried and 21 hourly associates to the unit. Now our Tele-Power Pole operation has everything it needs to go from raw materials right to finished goods.

The same is true of our Plugmold product line. We brought together rolling mills, punch presses, assembly tables, etc. which had been spread across different departments. We staffed the unit with a team leader, a buyer/planner, a shop floor coordinator, several manufacturing engineers, and a group of capable operators.

Bringing Employees On Board

While creation of this product-centered organization was certainly important and it helped to get our people closer to their customer, it alone wasn’t enough. We needed to make some dramatic changes in the way work was getting done. And that meant changing people’s mindset about how to manufacture our products.

We learned that bringing people on board is probably the most difficult part of implementing a program. That’s because kaizen is “backwards” from everything we’ve known or practiced about manufacturing here in the United States for the last 100 years. Instead of high-volume “batch” production, kaizen promotes making one piece at a time. High-speed is out, “takt time” is in. Large inventories, long viewed as an asset, were suddenly no good.

Bringing people on board is probably the most difficult part of implementing a program.

In effect, we were asking our employees to take everything they had ever learned about manufacturing and turn it around 180 degrees. And, on top of that, we set some tough goals that we expected the organization to achieve. We told our people that we wanted them to:

- turn around every customer order in 48 hours.

- cut product defects by half—every year over the prior year.

- improve productivity by 20 percent over the prior year—every year.

- increase inventory turns by more than six times what they have been historically.

Naturally, there was some skepticism and resistance. In fact, I’m sure that most people thought I was totally off my rocker.

Overcoming Resistance

We took a number of steps to help address that skepticism including: establishing a training program, making a commitment to job security, emphasizing the linkage between profit-sharing and productivity improvements, establishing a quarterly recognition and award system, and launching our effort with highly visible projects.

Training Program

Although we had previously done some training in Deming’s principles, we initiated an intensive, wide-ranging training program in the principles of JIT and kaizen for our people. We made sure that everyone got lots of training up front, and that they continued to get the training they needed to improve their skills.

The training is very action-oriented. We spend a long day in the classroom, followed by four days of doing an improvement project (kaizen) on the shop floor or in the office. People are taken off their regular jobs for the week to focus on kaizen. As a result, we get a combination of training and work improvement/simplification all in one.

Over the past three years, we have done several hundred major, full-week kaizens. Nearly all of our people have participated in at least one, and most have had multiple experiences.

Job Security

One of the errors some companies make is to try to use productivity gains as an excuse to eliminate people. This is fatal. You simply can’t expect people to participate in finding ways to improve the workflow if they are afraid that they will improve themselves right out of a job. The objective has to be to use freed-up people to support growth without adding headcount.

One of the errors companies make is to use productivity gains as an excuse to eliminate people.

We addressed this head-on with a commitment to job security: We promised that no one would lose his or her job because of changes of improvements under kaizen. Instead, we agreed that “freed up” associates would be assigned to kaizen teams to help find more improvements until we need them for new projects or because of increased production. In our particular case, and, for that matter, in all the companies where I have implemented this process, increased volume growth has absorbed all of the associates we have freed up through kaizen. Should our growth slow, we have plenty of insourcing opportunities to keep our associates employed.

Profit-Sharing

A critical element of bringing our people on board and keeping them motivated is our profit-sharing program. Although Wiremold has had profit-sharing for many years—dating back to 1916—it hadn’t been very lucrative for employees in recent years. In fact, the pay-out ratio was about two percent of salary.

As a result, we already had a program that would translate our improvement efforts directly to all of our associates. And it has. Profit-sharing payouts have more than tripled since we started this effort. And we’ve set a clear kaizen goal of getting profit-sharing to 20 percent of salary.

Associate Recognition

To further support our efforts, we established a quarterly program to recognize associates who demonstrate outstanding commitment to the process of continuous improvement. We call it the President’s Award.

Our product team leaders nominate people from their teams who have done an outstanding job of living the values we’ve taught. We honor two outstanding associates each quarter with a small cash bonus and an additional 12 associates with gift certificates for dinner at a fine restaurant.

While the economic value of this recognition may seem small, being selected for a President’s Award has tremendous psychological value and has become a coveted reward in our organization.

Kaizen in Action

Because the kaizen process is dramatic, just seeing it in action also helped to overcome a lot of employee skepticism and objections. As we’ve introduced kaizen to each of our operations, we’ve found that it works best when we begin with a big, visible project to show people we are serious.

At our plant in West Hartford, we selected several high-profile projects for our first kaizen team. Almost right away, employees could see us knocking holes in walls and moving 100-ton presses around—some of which had never been moved before.

Some of our earliest projects involved pursuing major reductions in setup time—and yielded dramatic results: our first automatic punch press kaizen team reduced setup time from two hours to just five minutes, and our rolling mill setup team went from 14 hours to less than one. In both cases, much of those savings were generated by identifying external setup activities that could be completed while the machine was still running. Other savings came from eliminating manual operations and standardizing or simplifying equipment. None came from big capital investment.

Because the kaizen process is so dramatic, seeing it in action also helped to overcome a lot of employee skepticism and objections.

In the case of the rolling mill setup, the old way was to wait until one job was completed and the equipment was shut down to select the die and stage the steel for the subsequent job. The kaizen team defined preparatory and planning activities that could be completed while the first job was still running. They also eliminated a number of manual operations and identified opportunities to switch to pneumatic tools to speed up other operations.

The first punch press setup reduction team also identified changeover activities that could be completed while a job was running. They also standardized all of the nuts and bolts used on the equipment (previously there were many different sizes, each requiring a different size tool.) And they installed quick-change clamping devices to further cut setup time.

The punch press is a good example of continuous improvement. Without understanding the possibilities, many companies would be happy to take a two-hour setup down to one hour—a fifty percent reduction. In our case, we went from 120 minutes to 5 minutes—a 96 percent reduction on the first kaizen. But we didn’t stop there. We kept working at it and got that 5 minutes down to 1 minute—an additional 80 percent reduction.

Tackling Monuments

At some plants, we’ve started by tackling one of the “monuments” in that particular factory. For example, our Walker facility had a huge rotary system with about 150 stations for lacquering certain metal components. The lacquer line had been there for years and consumed about 900 square feet. It was constantly breaking down and was hard to keep clean. It was also located in a key area of the plant that could be better utilized for other operations. But no one questioned whether the lacquer line was the best way to get things done.

The kaizen team that took on the lacquer line started work on a Tuesday morning after a full day of kaizen training. By Thursday, they were tearing the lacquer line down and throwing it away. In its place, they put two 2-foot by 2-foot boxes, each containing one lacquer station and serving one assembly line. The new arrangement allowed us to achieve one-piece-flow, reduce down time, nearly double output and, most importantly, free up a key part of the plant to give us a better layout with more flexibility.

Sometimes you just have to take a leap of faith. We announced early on to our people in West Hartford that we were going to close our 70,000-square-foot warehouse, which was a separate facility about 15 miles away, and move the warehousing operation back into our main plant. The situation at the time was that both facilities were full to the rafters and material was being stored outside the warehouse facility in about 60 rented tractor trailers. The initial response from our people was, “it’s not possible.” Frankly, I occasionally had doubts, too.

But, after about one year, we not only closed that warehouse—giving ourselves 70,000 square feet of currently empty space—we succeeded in freeing up half of the space at all of our locations.

Management Must Lead

Which brings us to the role of senior management. You can’t drive the kind of changes required from the bottom up. Without a commitment from top management, you might as well not even start the process because you are doomed to failure. But commitment alone is not enough. Knowledge about the kaizen process and how it works is also necessary—otherwise, you’re just a cheerleader.

I believe that to really succeed, the company’s leadership must not only be on board, it must lead the effort.

We did a number of things to make sure that everyone at Wiremold understood my level of commitment. First, I wrote a training manual and then led the initial training programs for the first year—personally training about 150 of our people. If that didn’t make my commitment clear to everyone, I was a frequent and active participant on kaizen teams. I continue to try to take a highly visible role, serving as the company’s kaizen “consultant” as we introduce the process to each of our acquired companies.

Second, we established a sizable JIT promotion office and we started sending the members of that team to Japan for a two-week training program. To date, approximately 50 of our associates from various Wiremold companies have been to Japan for training.

Finally, perhaps my most important role in the long-term success of the effort is to never be satisfied, to keep raising the bar and asking: “Why? Why? Why?”

The problem is that, like most American companies, we assume that there is some “right” way of doing a thing. We get trapped by the idea that there has to be some endpoint. How, with I believe that to really succeed, the company’s leadership must not only be on board, it must lead the effort. three years of kaizen under our belts, people still ask: “When are we going to be done? We must be almost done.”

While you want to praise people and tell them they’ve done a really great job—because, in truth, they have—you can’t stop to take a bow. I think that’s one of the hardest elements of kaizen for those of us raised in a traditional manufacturing environment. It’s my job to keep reminding people that with continuous improvement, we’re always searching for a better way. We never get done!

Sustaining the Effort

Some employees have made continuous improvement an obsession. For example, the team responsible for punch press could have stopped after their first kaizen, satisfied with the 96 percent improvement in productivity. But they continued to kaizen the process, making gains with each effort.

In general, our people are less resistant to change because they’ve seen some amazing things happen. Even so, it can be hard to keep the process moving ahead. We host kaizen workshops from time to time. Bringing in “outsiders” to participate in a seminar in one of our plants helps generate new ideas and reinvigorates our own program.

Over the long term, the only real way to sustain the process is with a fundamental change in the organization’s culture. We’ve worked hard to make kaizen a part of our culture, and to encourage the values of teamwork, constant change, and constant learning.

This is more than simple platitudes. Our training, job security, and profit-sharing programs all contribute. We also work hard at communications. Everyone in the organization knows what our objectives are and where we stand against them. Every two weeks, our team leaders present their progress towards their goals to me, my direct reports, and each other.

Three Tips for Getting Started

It’s not easy to get started and it’s not easy to sustain, but, I think everyone at Wiremold would agree that the results so far are well worth the effort required. The nicest thing of all, however, is that our progress to date is totally attributable to Wiremold’s associates. They know it and are proud of it.

Our people are less resistant to change because they’ve seen some amazing things happen.

We’ve only scratched the surface, but our expectations of how much further we can go makes our jobs a lot more exciting. In summary, there are three tips that anyone getting started should keep in mind:

- Changing people’s mindset is a critical part of the job. People are naturally skeptical and you have to take dramatic and sustained action to overcome objections. In the long run, you must change the culture of the organization. The “concrete heads” must go.

- Senior management must “lead the charge.” That means not only at the beginning, but throughout, continually putting pressure on the organization. Lack of leadership attention is one of the major reasons that improvement programs die within a year to 18 months.

- This is a long-term commitment. You have to acknowledge up front that there’s no end point. Be prepared for your people to ask, “Are we finished yet?” And be equally prepared to answer, “It’s not good yet”…even when you think it is.

A final thought: I want to acknowledge that we didn’t get here alone. Our program is now essentially self-sustaining, but we continue to work closely with kaizen experts from the Japanese firm of Shingijutsu, and its American affiliate TBM Consulting Group, as well as Moffitt Associates.