Dear Gemba Coach,

Is lean really valid in all situations? That sounds like ideology to me!

Can you think of a situation where you can’t ask yourself: Do my customers smile with satisfaction when they use my product or service (or frown with annoyance)? Or: Am I only making one when I’ve sold one (or procuring one when I’ve used one)? Or: Is all the hard work we’re doing really necessary to get the job done for customers (why would customers want to pay for me doing my accounts, having them certified, etc.)?

Yes, I’m cheating. I’m assuming lean = deep thinking, not lean = operational excellence.

You’re asking a deep question, which did make me think a lot, and unfortunately, I’m not good enough a writer to answer simply, so I’ll be using long words – please bear with me.

In studying Toyota’s success in the late eighties, we all thought they had hit upon an organizational solution. After all, this was our obsession at the time, with business process reengineering and whatnot (I plead guilty, I wrote a book about it). We thought that if we could only:

- Map value streams and organize around value streams with value stream managers and so on,

- Improve the flow of value by having multi-process cells delivering full products – or fuller chucks of products, rather than having everything broken down by specialized departments,

- Accelerate the flow of value by establishing pull systems simulating customer demand through the cell network rather than scheduling everything through the central MRP,

- Engage everyone in kaizen in seeking the perfect processes by eliminating variation,

Then, somehow, we should reach a Toyota-like level of competitive performance. We often did improve operations visibly.

It was crazy days. At the time I was juggling my doctoral research, business school teaching jobs, and my first lean consulting assignments. I was helping a bunch of crazy guys create cells in factories in a week.

On the night of Wednesday to Thursday, we moved the machines around to create flow (imagine moving a several tons robot to create a cell) and hoped the factory would restart on Thursday morning – which it mostly… didn’t.

Yes, this was pure ideology. But to be fair, considering the state of industrial thinking back then, in the early 1990s, it also worked, often spectacularly.

We’d learned this approach from ex-Toyota consultants who had adapted Toyota’s “kaizen” into these five-days “break the logic” workshops to fit with what Western companies were asking for – quick results with a repeatable method. Trouble is, of course, that when all you know is a hammer, everything tends to look like a nail.

Organizational vs. DevelopmentalThese techniques are not meant as organizational solutions to apply and magically make things better. They are meant as developmental exercises to practice seeing your current situation in a new light and find opportunities for improvement.

At the same time, I was observing, purely as a researcher, how Toyota was proceeding with one of its suppliers. I was very puzzled because Toyota engineers had a completely different approach. Yes, they did start by organizing a rough pull right away from the production cell to a logistics area every couple of hours. But then they mostly asked the supplier’s engineers to pull out their own specs for their process and fix issues one after the other. The big fight then was on batch size – which I guess is organizational to a degree. But mostly they left the organization alone. What they did was solve one problem after another. Results were not only spectacular but also sustainable.

Toyota’s lean was developmental. By giving set exercises to do, it expected people to look deeper into what they were doing, click, and take initiative from insights. Think of it as an Asian approach, like meditation or martial arts. I’m told that the original meaning of Kung Fu is “any discipline or skill achieved through hard work and practice.”

In this worldview, the student takes responsibility for her learning (as opposed to our notion of “training” people – often against their will), and the master sets formal exercises for the student to practice and practice and practice until the student “gets it.” There are many such exercises in lean:

- 5S

- Stop and call at every doubt

- Pull at takt time

- Looking for seven wastes in any work cycle

- Flow and layout

- Problem-Cause-Countermeasure-Impact problem solving

And so on.

These techniques are not meant as organizational solutions to apply and magically make things better. They are meant as developmental exercises to practice seeing your current situation in a new light and find opportunities for improvement.

These developmental practices work on the following basis:

- Use a lean tool to see the waste in what you observe at the gemba;

- Imagine an ideal, guided by lean principles;

- Recognize the obstacles, and observe as many factors as you can;

- Imagine the next thing you’re going to change;

- Try it, see what happens, and reflect deeply about the underlying lean principles.

This develops you both by deepening your understanding of situations, learning to work with others and listening to their point of view, and building together steps towards the ideal. Practicing the tools with the principles in mind develops awareness, thoughtfulness, and resourcefulness – in other words, creativity or inventiveness.

The Clever Part

If you see lean as a bunch of organizational solutions, then, yes, it quickly becomes an ideology because these solutions don’t necessarily apply. For instance, at the two ends of the volume continuum they don’t make much sense:

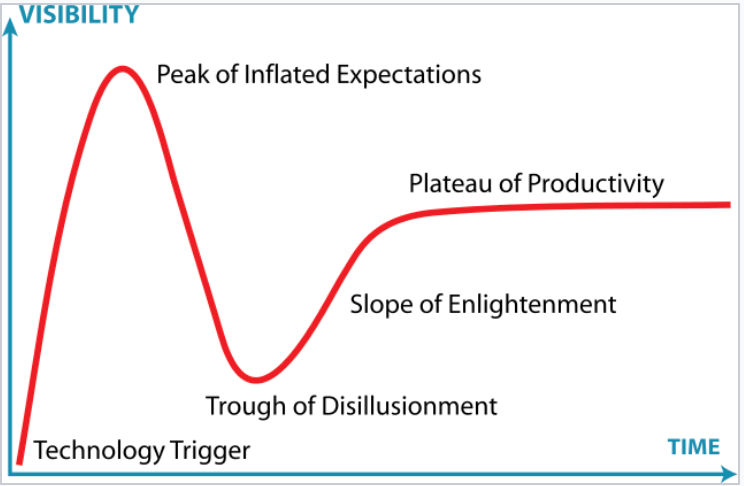

- If you’re in full boom, can sell everything you produce, such as if you’re working a new technology everyone wants, then don’t worry about lean. Set up resources as quickly as you can while the demand lasts (hoping that it will, the specter of the Gartner hype curve always looms)

2. If you’re making single, all-different, customized products then many of the mass production ideas such as continuous flow and batch sizes simply don’t apply immediately.

2. If you’re making single, all-different, customized products then many of the mass production ideas such as continuous flow and batch sizes simply don’t apply immediately.

However, if you see lean as a developmental method, then, of course, it’s always valid. The questions it asks are always sensible and interesting even if the answers often feel messy and strange – and often appear impossible. That’s the point.

Now for the really clever part: what makes lean transformational?

The fact is there is an organizational element to all lean exercises. One of the key insights we’ve picked up from Toyota is to start with the precision logistics. For instance, the team of AramisAuto.com, a digital company that sells cars over the Internet, has spectacular results (recaptured growth, double the EBITDA) by starting with establishing a pull system in the flow of cars.

At first, everyone resisted because the story in the company is “we can’t control transport.” But then through sheer persistence, people learned that, yes, you could set up precise appointments for trucks to move the right car at the right time for the set date with the customer:

Organizational ? Developmental

And then, in other cases, some of the purely developmental exercises the teams set themselves led to new organizational solutions. For instance, the refurbishment factory that prepares used cars for resale on the site (the company offers a serious guarantee) had an on-going recruitment problem. After looking into the problem deeply and trying many things, they concluded they needed to have their own local HR function rather than attempt to do everything from headquarters and hired a local HR which had a hugely positive impact with many HR subjects at the plant, which made keeping the pull system going so much easier.

Developmental ? Organizational

Rather than oppose organizational and developmental, we can make them work in tandem. Organizational becomes developmental, developmental becomes organizational, and this is the dynamic that creates the adaptive solutions that support profitable sustainable growth by involving all people all the time in building together the organization of tomorrow by responding smartly to the challenges of today.

I truly believe this kind of thinking is relevant to any situation – if one keeps in mind that all we know about lean, TPS, tools and so on is a starting point, not an endpoint. Lean gives us standard exercises by which we can begin our practice to discover how to lean organizations by developing people and discover… what we discover. The path starts at the same place because this we know, and then each person forges their own journey, with destination unknown.