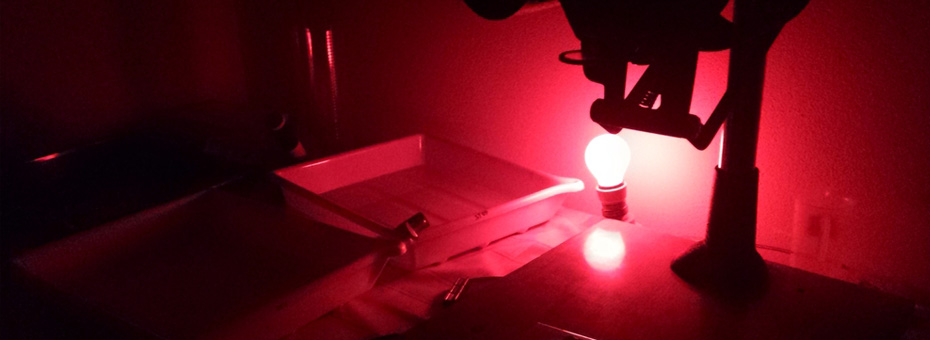

On the shop floor, we made light sensitive photographic film. Our manufacturing floor was a darkroom: not the low-level lights you see in the darkroom movies but rather no light. Complete darkness. Those who worked in that environment became familiar with it. They had to. For those of us who supervised or led operations, we found ourselves in the darkness on the everyday shop floor. We led from our desk, where the light was.

Lean seemed so simple when I was first introduced to it. “I got this,” I thought. My first task was to understand value vs waste. “Go See,” my sensei said. “Sure,” I thought. This is so easy; I don’t really have to do it. I got it.

The Ohno circle had been described to me. I was to stand in a spot and just observe. See what I see. But why? I understood the basic concepts. Certain tasks are value added. Other work is not. “Let’s get on with the more important stuff,” I thought. Although this gemba was safe, the thought of going there was scary to me. The truth was I didn’t really know what happened there and I didn’t feel as though I could go see with absolute confidence. And that stopped me cold. Thinking back, I did not want to admit I was scared. Scared of the unknown. Scared to be seen as unknowing. And this allowed me to convince myself there was nothing to see.

What can a single observation yield with so much activity on a shop floor at any given time? As I would learn eventually, a lot. It was the thought of not adequately completing the homework assignment my sensei had given me that motivated me to take the first step. I approached one operator. It was someone I knew, not very well, as there were so many in the organization. But she was a friendly face. I explained I wanted to learn. I humbled myself. I explained my task. Eva, this operator, was so open to sharing her work with me.

She told me to put my hand on her shoulder and she would lead me to her workstation, a spooler. We walked together through the light curtain and took a right turn. It was pitch black. I was hesitant. I wanted to slow down. I had to make a choice between letting go of Eva’s shoulder and being on my own in the darkness, or keep up. Likely she could feel me slowing down. “My spooler is across the room. We still have a while to go,” she teased. I could tell she had a smile on her face. I may have heard a faint chuckle. It made me smile too. And that helped me to relax a bit. The darkroom was loud. I could hear the various machines running, slitters cutting film, spoolers spooling and packaging materials sliding overhead. I could also hear the shuffles and call-outs of the operators as they moved through the room. I knew where each person worked and I was surprised at how easy it was to match the voice with the person I knew from the light. The space was cool and that surprised me. I don’t know why. It made for a more comfortable working environment.

Just before we arrived at Eva’s spooler, she walked me past the racks of WIP. Amazingly, without any theory of value and waste she described how the work should flow. She explained to me how to read the card that described the product by feeling. She also taught me how the feel of the film helped her identify the product. We grabbed some film. She took me over to the spooler and took my hand and showed me how she would thread the machine. And then she went to work. As she worked she described what was actually happening. I couldn’t see it. I could hear the movement of the spooler and the drop of the plastic spools and containers as she worked.

And then I heard nothing. Eva explained that sometimes the materials get stuck in the line. She wasn’t tall enough to reach up. “I’ll be right back,” she told me. It was very awkward standing in dark. I could hear how busy everyone was and I was just standing there. I wasn’t yet comfortable to move around freely. (It would take me many visits to eventually be able to isolate sounds and voices to know exactly what was happening.) Eva came back. She explained she went to get a stick she kept which allowed her to reach up and knock the packaging back into place. She re-started her machine, and explained every movement she was making. There were never more than 5 or 6 good spools before something interrupted her. I was shocked. Plastics jammed the line. Film was tough to load. Other people interrupted for this or that. One roll of film didn’t feel right to her so she took a snip and walked into the light. As she suspected it was stored under the wrong label. I had no idea there was this much non-value added on my own shop floor. I felt the frustration of trying to do a good job.

Intuitively I did get the concept of value. I thought that was all I needed to be lean. I realized in that first visit into the darkroom that knowing the concept is not what going to gemba is about. Lean is not a race to be the smartest. Maybe it is a race to see who can look at the world through different eyes? Eva’s eyes? The customer’s eyes?

Even though that first step into the darkness with Eva was eye-opening, I was still hesitant to go out a second time. All the same thoughts ran through my mind. I got it. I got it. I had to fight that same reluctance I felt the first time. Eva wasn’t working that day. I tried this time by myself. It was awkward. I know I was far from the epitome of grace as I tried to get my bearings. But I did. And my eyes opened even wider. It still took a long time to get a regular go see routine. It was awkward for a while. It still is, the first time I visit a new place. It is easy to create a reason to avoid the awkwardness. It is hard to embrace it as part of understanding what I do not know.

Eventually, as a leader, I learned it isn’t one trip to see the work or even two or three that matters the most. It was the regular pattern of going to see that I needed to develop. In doing so I started to really see the chronic problems that occurred, not just in Eva’s operation but across many operations. These problems, which extended across many of my production areas, mattered most to me because they were the ones I felt ownership for. Seeing them first hand helped me understand them truly before setting out to eradicate them.

I learned that there was something better than the seeing the problems themselves come to light: seeing the ingenious ideas operators had to deal with them. Eva’s idea, for example, of comparing the feel of the product with the identifying card iterated into a breakthrough in the elimination of one of our biggest defects, spooling the wrong product into a box. Seeing the people who overcame the very obstacles I witnessed created the stories of hope for me and for my team. Anything we needed to do could be done. I saw it. I saw it in the dark. It just took the humility to go out there regularly and watch.