Lean is widely known today and celebrated largely as a powerful system for eliminating waste and improving quality. And yet we believe that to frame lean as merely a set of tools and principles that improve processes and increase efficiency fails to capture its true power. We believe that the essence of lean—as it applies to all functional areas of the enterprise to different industries and sectors—is continuous improvement, with learning at its core, as noted by Daryl and Torbjorn Netland.

Lean is about learning. Learning to find real problems, learning to face the limits of our current knowledge in light of these problems, learning to frame the gaps as learning challenges, and finally, learning to form and share actionable solutions. As such, lean is really about learning-to-learn.

The only secret to Toyota is its attitude towards learning.

– Isao Yoshino, from Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn by Katie Anderson

Based on our cumulative experiences from studying and guiding lean transformations, we have come to realize that a lean transformation is in fact a progressive, transformational learning journey, consisting of at least three phases. Firstly, management might decide to embark on a tool-based lean implementation. Some implementations will then advance as journeys of transformative leadership development.

Then, the few that actually succeed will transpire towards building a learning-to-learn capability, both as individuals and as organisations.

Some years ago, one of us was leading a lean transformation in a multinational organization. What began as a global initiative to adopt lean best practices quickly transitioned into one of lean leadership development, where A3 Management and Toyota Kata were identified as means for realizing structured problem-solving in operations. However, given the complexity and cross-functional nature of many of the problems that emerged, the limits of our Starter Katawere soon uncovered. The situation demanded something more.

Build Your Learning Scaffolding

In the absence of a culture of organisational learning, a structured playbook to scientific thinking is important. A3 Management and Toyota Kata, which Toyota practices regularly, serve up options from a buffet of lean tools together with the thinking process needed for purpose-driven problem-solving. Where zero improvement habits exist, installing routines based on these two popular best practice approaches to kick-start discovery and learning is sensible, and will drive benefit. But for how long?

Without this improvement foundation, learning becomes anecdotal, caged-in by the structured, over-mechanisation of thinking. It’s good (and necessary) to know where you currently stand in relation to your target condition, and indeed, to iterate towards new conditions. And while we value the improvement and coaching kata, we wonder if the rigid routines of these kata paradoxically hinder flexibility and the advancement of personal development?

To unleash curiosity, we suggest that there may be more to the story. The teacher-manager can steer the inquiry process by posing thoughtful questions to the learner, which often unearths shared unknowns. Controlling managers, on the other hand, coax learners towards their own thinking, sometimes using Toyota Kata as the vehicle. Control-managers get what they want, and the learner believes it was their creation, but, in reality, thought-potential and creativity were unwittingly muzzled. The ultimate learning experience is suppressed.

When the driving force behind improvement flounders, routines are quickly abandoned, and learning decelerates. The discovery process should in theory perpetuate. And yet if the learner relies on structure and logical reasoning alone, without banking self-awareness along the way, continuity in learning also grinds to a halt. As such, the competence to pose fresh questions, to reflect and self-learn, remains uncultivated. The ‘learning scaffolding’ collapses, and there is nothing else to hold it up. Toyota Kata cannot be blamed for this outcome. It is merely a product of how this type of learning journey is designed and executed, and subsequently fails. Unfortunately, the Toyota Kata is too often adopted as the end rather than the means.

The truth is improvement routines and resultant optimization are never enough. Today we are diving deeper into stormy economic waters, and gains from process improvement will not secure survival and employment stability. The elementary rigidity created by routine will need to evolve into something more forgiving, and the tool needs to fulfil its duty to propel discovery. We need independent, perpetual, self-actualising thinking machines to hatch from the discovery process. We need more organic (not mechanistic) systems of enterprise. As such, we suggest a need to supplement the improvement and coaching kata with a third type of kata – the learning kata.

Towards a Learning Kata

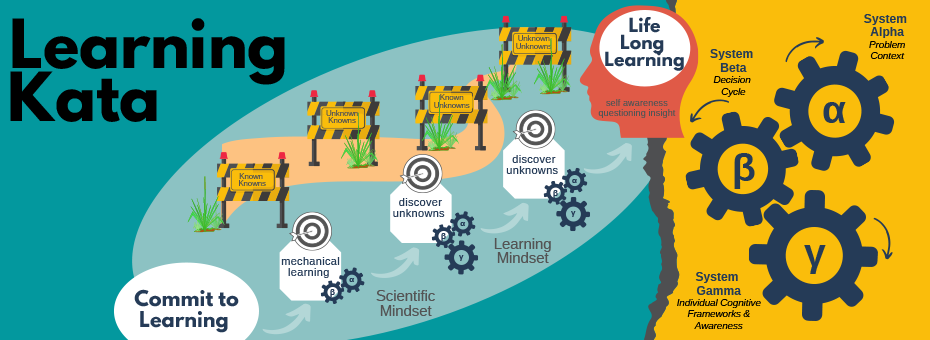

The Toyota Kata – specifically the improvement and coaching kata – provides an excellent approach to create scientific thinking capabilities in people. However, in terms of learning, particularly action learning, the scientific method is only one piece of the proverbial puzzle. Thoughtful leaders can in fact develop this system intentionally. In Developing Effective Managers, Reg Revans (the originator of action learning) made a formal attempt to develop a theory of Action Learning based on three interacting systems:

- System alpha – focuses on defining and understanding the problem (including the underlying management values that could well be causing the problem in the first place);

- System beta – focuses on resolving the problem using the scientific method;

- System gamma – focuses on the learning as experienced uniquely by each of the participants (through self-awareness and questioning).

Though the improvement kata partially fulfils the requirements of system alpha, and the coaching kata presents a scientific method which fulfils those of system beta, there seems to be a lack of a third kata to fulfil system gamma, what we will call the learning kata.

The first two systems build the scientific mindset. They essentially shift the learner beyond their preconceptions and unconscious bias to understanding the problem and its causality, with greater certainty. The scientific, evidenced-based nature of the learning is fundamental to decisions based on fact and observation, as opposed to gut-feel and confirmation bias. There is tremendous value in comparing what we think will happen in theory, to what actually comes from each experiment performed – as each failure brings with it further, incremental discovery. Combining the science behind experimentation with regular routines leads to the muscle memory of problem-solving skill. This aids in the development of a “community of scientists”, solving problems every day in a structured way. The manager and learner progress together through the learning routine. This is a critical part of the journey.

However, what this fails to do is prepare the learner for the extraordinary, as they progress from known knowns to facing unknown unknowns. To Revans, this first type of problem (known knowns) were simply “puzzles” – difficulties from which escapes were otherwise known. Solving complex problems, on the other hand, requires reflective, insightful questioning. In asking fresh questions, the learner can uncover any underlying assumptions and create new connections and mental models.

Make no mistake, the mechanistic nature of the improvement and coaching kata promises to cultivate problem-solving skill and an indispensable scientific mindset. It presents learning moments with each failure or each gap closed. Yet it falls short of transitioning the mature student to personal mastery and self-awareness – enabling them to think through situations more challenging than the familiar. Critically, the learning process must become “about the self”.

In the spirit of action learning, specifically system gamma, the journey to self-awareness prevails in the absence of any form of power-distance. System gamma presents a learning kata to arouse peers to advance beyond the limits of their current knowledge through synchronous learning, with each participant making a formal commitment to both action and learning. As such, the learning kata’s triggers are more than just a standardised questioning process – and must foster challenge as well as unique questioning insight to spark curiosity through the deep awareness that comes from personal reflection. It is a pact that the learners must make with themselves.

This contrasts with the traditional scenario in which managers drive the subordinate’s learning process (likely in a direction to suit the manager’s value system and life goals) to achieve in many instances end-of-event learning. Instead, with the learning kata, peers drive the questioning and reflective discovery process together, sharpening and cleaning the lens through which they see, to understand and deal with new complex problems. In time they cross-over to independent, self-aware, self-motivated, life-long learners.

The social learning that takes place in the learning kata enables symbiotic learning, between peers. At first this may seem rather uncomfortable to many managers – as they face the vulnerability of admitting the limits of their current knowledge in front of colleagues and subordinates. However, the overriding value that guides this learning approach is a pragmatic focus on learning for the sake of more effective instrumental problem solving. As every good teacher-manager knows – to be a good teacher, one must first become a good learner.

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

Develop Scientific Thinking, a Foundation of Lean Management in the 21st Century.