“Practice the art, respect the science.” – Jester King *

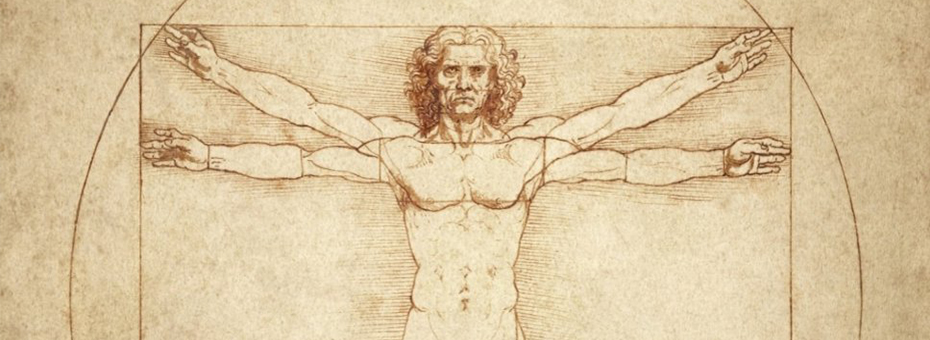

Has the body of thought and practice known as “lean” too long mired itself myopically in the world of “science” to the exclusion of an equally, or even more, important dimension of human experience: art? If lean has been stuck in science class, what would happen if it wandered across campus to the art studio?

Those are big questions, indeed. To explore, leading thinker and coach on lean applications in the messy world of construction,Tom Richert convened a group of curious artists and musicians to engage in a surprising experiment: how would they respond to being introduced in a structured way to lean thinking & practice?

Tom’s landmark initiative has produced its first output with the publication of Lean Conversations: The Energy of the Creative Ethos in Your Life and Work. This book captured the inquiry and reflection of a group of artists who immersed themselves in the fundamentals of lean for three intensive days with the goal of better understanding ways to spearhead positive change by leveraging an artist’s sensibility. The title reveals little of the serious intent of Tom and his band of artisan collaborators, unless you think of the essence of the initiative as introducing a new type of conversation, like Stone/Patton/Heen’s Difficult Conversations or Patterson/Grenny/McMillan/Switzler’s Crucial Conversations or even David Bohm’s On Dialogue.

“Something is missing from the lean dialogue: an artistic dimension with deep connections to the emotional and even spiritual sides of humans engaged deeply in their work.”So what is the conversation? It’s about linking lean thinking with art, for sure; and beyond that, linking it with emotion and even spirituality, too. Tom is convinced that these were elements of Toyota’s business system from the beginning, elements that have been lost as lean thinking has dispersed and diluted. I would not disagree. One of the provocative observations from the group of artists learning about lean is that “Lean is a way of thinking in search of a language.” Actually, though, even calling this way of working and thinking “lean” was an attempt at establishing a language to begin with. Study of Toyota’s ways of working was already underway before Womack and his global research team labeled it “lean production” and established it as the next paradigm of free enterprise in the late 1980s. Before the moniker “lean”, it was mostly called JIT (rhymed with hit), a selection of concepts and tools that quickly devolved into the deplorable OEM practice of pushing the holding of inventory onto suppliers.

Essentially, lean is PDCA (the interpretation by a band of Japanese business and academic leaders in post-war Japan of a series of lectures by Deming) with a focus on developing capability to eliminate the nemeses of value creation – waste – in its various manifestations (Toyota named seven fundamental types of waste or “muda”) and attacking it at its ultimate source which exists at system and sub-system levels.

“We understand and practice PDCA better than you industry people,” is a key takeaway from this group’s work. In the book they note that: “The potential for the Lean approach to create a very desireable human system of work appealed to the members of the workshop because there was a focus on helping the individual use work to develop and grow. In this sense, Lean mirrors the creative ethic they rely upon in their artistic work.”

“One of the provocative observations from the group of artists learning about lean is that ‘Lean is a way of thinking in search of a language.’”I referred to Tom’s work (which I like to call “Lean and the Arts”) as a landmark initiative. One of the unexpected observations that emerged related to the underserved “emotional” and even “spiritual” dimensions of lean thinking & practice. Tom and his band of artists argue that the narrow if powerful set of technical tools that comprise most lean practices are fine as far as they go. They make technical matters technically better.

Many of us have long argued that lean practices without the underlying thinking are stripped of their power to transform and make any situation better. They aren’t lean at all without the thinking that engages the practitioner in a process of continuous self-improvement.

Tom argues that even adding the “thinking” dimension still falls short. Even with the thinking, lean practices represent logical thinking and rational approaches to problem solving and decision making. Scientific thinking, if you will. Tom argues that there is something still missing: an artistic dimension with deep connections to the emotional and even spiritual sides of humans engaged deeply in their work.

This argument reminded me of an experience ten years ago when David Verble and I taught the first pilot of the Managing to Learn (MTL) workshop. At David’s suggestion, we developed a workshop based on a mix of my MTL book, Toyota’s A3 Process, Toyota problem-solving approaches, and coaching & learning devices such as questioning based on Edgar Schein’s four types of humble inquiry. Since then we have added additional touches such as Schein’s taxonomy of four types of questions and a dose of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast & Slow. We’ve always felt the whole process was underpinned by not only Toyota but also by John Dewey. And Steve Spear should be given his fair share of credit, too. The workshop itself has been taught and improved by many including Margie Hagene, Eric Ethington, Jack Billi, and Tracey Richardson, and who knows how many people at how many companies. Most recently, an energetic team at LEI has developed a wonderful “MTL Remotely” distance learning version (by the way, it’s great!).

Back to the first time David and I taught the two-day workshop for LEI, in LA in 2009. I recall a lively exchange with one enthusiastic participant. I had suggested that, even as we moved toward more fact-based decision-making, there was still a place for intuition (for a related thought, see this week’s Post Cultivating Intuition at the Gemba.) That suggestion greatly disturbed one participant: “But that just lets us devolve back to where we started – making decisions based on opinion rather than data. That’s exactly what we need to get away from.”

My reply, which failed to satisfy him, was this: “all this work to be clear about our thinking – the work to gather the real facts at the real place, to clarify decision criteria so we can think together and discuss/debate effectively and respectfully rather than talking past and over each other, with decisions made based on positions of authority and loudness of voice rather than on a consensual view of what steps we can take to close knowledge gaps (option gaps, too) and learn what we need to learn – doesn’t eliminate all intuition. This work enables a more scientific approach to problem solving, sure, but it also serves to make our intuitions better. There is still a place for passionate advocacy and for holistic reading of situations so that decisions simply ‘feel right’. David’s “lean epistemology” questions entail both quantitative (just the facts, please) and qualitative (how do we feel about this?) dimensions: “What do you know and how do you know it? What do you need to know and how can you learn it?”

Looking back I think this is one of the things Tom Richert is getting at with his admonition that we not forget the emotional side of human engagement in organizations. Point well taken, Tom. (Besides, maybe the scientific method is a myth.)

As I heartily recommend this book, I should caution and Tom would agree, that this inaugural product is only a first baby step. If Jean Cocteau’s famous observation that “art is science made clear” has meaning, we can all benefit from further exploration of the relationship between lean thinking and art & science. I suggest you read the book, let it sink in, ponder it slowly (not letting instinct take over and jump to conclusions) and join me in hoping for a next installment from Tom and his band of artists.

Is lean thinking art or science? Yes.

* Jester King – My favorite craft beer brewery, half an hour outside of Austin, Texas.