Dear Gemba Coach,

Can lean really deliver more meaningful work for everybody? Isn’t this overpromising to workers and disrespectful to them because management really can’t deliver on it?

Thank you for this very intriguing question and its backup explanation: I must admit it took me off-guard (as in “huh?”), and thus a good starting point for deeper discussion.

Your question took me by surprise because it seemed obvious to me that management cannot create meaningful work. What employees consider to be meaningful or meaningless is strictly up to them. What management can indeed do is strive to create better conditions for people to find meaning in their work, which is a rather different proposition, and yes, can be sought at all levels, from the receptionist (welcoming guests is profoundly meaningful) to doctoral research (which, by the way, with a poor thesis advisor can become rather meaningless).

I honestly don’t believe any job is meaningful or meaningless in itself. Lean is not about either narrowly defining the job (that would be Taylorism) or controlling the person (that would be Taylorism as well) but about looking at the relationship the person has with their job, and the relationship they see between their work and their customers. Whether any job, from CEO to cleaner is meaningful depends of how the people themselves relate to this job – how they interpret it.

7 Means to Meaningless Work

For argument’s sake, let’s consider a gemba we’re all (unfortunately) acquainted with: hospitals. During gemba walks in hospitals, I’ve come across orderlies who make a special point of making every patient more comfortable in small ways, while some doctors complain about the meaninglessness of working with the hospital bureaucracy and healthcare system, and hospital CEOs reduce their jobs to budget control without ever considering patients, and, not surprisingly, feel their job is somewhat absurd.

People are not robots. No one can promise meaningfulness precisely because meaningfulness is something people devise by themselves, and this often depends of very changing conditions, such as their moods, their focus, who they work with, how stressful the situation is, and, yes, even maybe culture.

However, if making work meaningful is hard, making it meaningless is rather easy – just treat people like robots. As new research shows, there are known ways managers can turn any job into meaningless work: (1) disconnect people from their values, (2) take them for granted, (3) give them pointless work to do, (4) treat them unfairly, (5) override employee’s better judgment, (6) disconnect them from supportive relationships, and (7) put them at risk of physical or emotional harm.

In lean, the first step of showing respect is making sure no one is at risk, either physically or morally, and clearly this is something we can commit to improve every day. Again, you can’t control people for risky behavior, but, as a manager you can work at improving the conditions to make risky behavior less likely and you can engage the people themselves in doing so, in order for them to commit to upholding these better conditions.

7 Means to Meaningful Work

What can a lean manager do to create the conditions of more meaningful work? There, the lean tradition has some clear experience:

- Place yourself next to the person and don’t decide for yourself what is meaningful or meaningless, but observe what they find meaningful and meaningless from their own perspective. You’re likely to discover they have a completely different take on their job from yours.

- Listen until it hurts to all the issues people face that makes their jobs feel discouraging or hopeless – even if you can’t solve them all or any. This is hard for managers, because they have to let go of being “deciders,” and start investigating with people what they themselves can and can’t do.

- Clarify “line of sight,” by showing visually to every person how their job affects their clients, both internal and external, and in the end the business as a whole, so they can see how doing their job well matters.

- Teach problem solving and support people’s problem solving efforts by sorting out things they can’t themselves and listening carefully to the obstacles they face, without solving the problems for them. As one person solves repeatedly a similar problem in different circumstances, they will discover more about the underlying elements of their job, and the meaning in that.

- Support kaizen, suggestions, and creative ideas so that people can have an impact on running their own work environment and work. This develops ownership both at the individual and team level.

- Train team leaders to deal with team issues, both individual and collective. People are not machines, and they have very human issues of worries outside of work, moods, getting along with some and not others, and so on. Training team leaders to handle those with finesse is a key component of people seeing sense in what they do. People join companies but leave their bosses or their teams when they don’t get along.

- Clarify progress paths so that each person can see what their next step is and where to start – what they need to do in order to succeed at this next step.

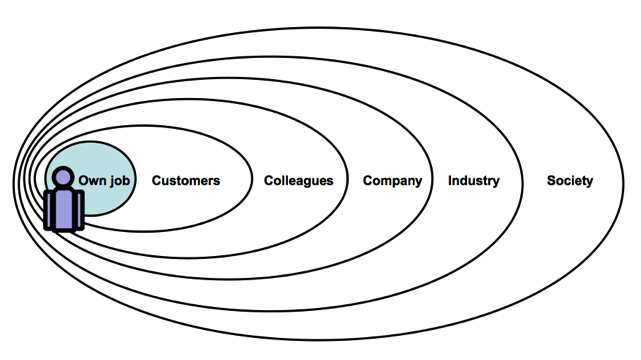

None of these practices are easy or obvious, but they can certainly be taught or learned. Can they provide a meaningful job to everybody? Probably not, but they can certainly create the opportunity for a meaningful job at all levels, from top to bottom. What we’re trying to do is to stretch the person’s feeling of responsibility from their narrow definition of their own job to a wider vision:

This is never a given, of course, and requires spending a lot of time with the people, observing and discussing. Whenever they’re left on their own for too long, or if they’re challenged by circumstances they will, understandably, retract to the narrowest definition of their job.

Which is why faster flows and quicker reaction to out-of-standard cases help tremendously by revealing in a very concrete way the impact of one’s job on the rest of the chain. JIT and jidoka are essential meaning-building tools: better JIT and better jidoka create the circumstances for more meaningful action and problem solving.

Does this always work? Mostly, but there are hard cases almost impossible to crack. The ones I’ve witnessed more often are:

- The professional who defines the job on their own terms (doing the work the way it should be done) and refuses to acknowledge that others have other concerns and compromises. This is tough, we’ve all been there, because in many cases they are indeed right – they know best how the job should be done – but other constraints are also real, so resolution requires some give-and-take. If they put their meaning, their pride, in never letting go of self-chosen “professional standards,” things get awkward.

- The employee who refuses to engage or, indeed, see any meaning in their job. They consider this is something they do because they must, and their life is elsewhere. As a result, they bring a negativity to the team that is very hard to deal with because they will sneer at any improvement attempt, and make fun of anyone who makes suggestions or goes the extra mile.

- Some people just don’t get along and when two such persons have to work together their personal dynamics will sooner or later overwhelm every situation and impact the team.

- The guy who knows it all and considers the fault is systematically with someone else, even when the team has agreed to give-and-take and look at their share of responsibility in a situation. Some people, luckily few, simply seem incapable of acknowledging they’re wrong at any time in any case.

I don’t know of any systematic answers to these extreme cases, other than whether with lean or otherwise this is clearly why (good) managers are needed.

Can management promise everyone will find the meaning they seek in their jobs? Clearly no, that would be absurd. Management, however, can commit to creating the conditions for meaningful work in every job, at all levels. This means first abandoning the idea that people are information processing machines, as with “holacracy”, and accepting that they are people with their own values, relationships, ideas, skills and, indeed, temperaments and moods. This also means letting go of the notion that people are tools to be used in predefined boxes (as with Taylorism or six sigma) and finding the fun in discovering new solutions with the people themselves, every day, every where.