It’s February, right? Because if we ever needed a reminder that Punxsutawney Phil lives on we just got our annual Groundhog’s Day media article debunking the false idols of lean, TPS, phrenology, and all them other new-fangled fads. This year’s model was a Wall Street Journal article titled “Companies Everywhere Copied Japanese Manufacturing. Now the Model is Cracking”.

The story argues that recent instances of companies such as Kobe Steel, Mitsubishi Materials Corp., and Subaru Corp manipulating quality inspections call into question the validity of what the Journal dubs the model of Japanese manufacturing. The article identifies said Japanese model as kaizen, or continuous improvement, which it defines as “eliminating unnecessary activity, reducing excess inventory, and using teamwork to fix problems when they arise.” The article notes the importance of eliminating waste, reducing inventory, and using teamwork to fix problems when they arise.

While some of the underlying facts may indeed be true, the generalized argument is a bit “truth-y” without being actually … true. In other words, the question it raises about whether work systems that rely on frontline workers who are coached by engaged leaders can survive without upper management is valid. But to use these examples to fault the model itself feels like a stretch.

Just to get this out of the way, this article fits in a long tradition of reporters jumping to conclusions about lean, or in this case, “Japanese manufacturing.” Jim Womack, who wrote two separate e-letters in response to prior Journal articles misrepresenting principles of lean/TPS, says these types of pieces “latch onto kaizen and JIT and other tools as the problem when these have nothing to do with any of the problems cited.”

John Shook also had a thoughtful response to a 2009 Wall Street Journal article “Latest Starbucks Buzzword: ‘Lean’ Japanese Techniques”, a piece that tagged this approach as a management fad, industrial engineering, a cost-cutting fix threatening employee’s jobs. Shook framed the article as a teachable moment, noting that Toyota’s two most radical innovations were proving that flow was possible even in complex product mix environments; and that to make this product diversity possible it “revolutionized the social dimension of work, respecting workers brains as well as their hands. So, factory workers became knowledge workers.” Contrary to the article’s implications, Starbucks was introducing lean in a manner consistent with TPS ideals—from the ground up, with individual input:

“Starbucks is approaching lean with the intent of providing their baristas with the skills to do better work design on their own, as they go along. This is in total contrast to the uninformed charge that baristas are being made into “robots.” If that is what Starbucks wanted, there are easier means to get there than their chosen method of introducing the concepts to each store and asking the baristas to work on their own unique solutions suitable to their own unique situations.”

I do feel compelled to call out one flaw in the article: “Japanese manufacturing” is not one thing, and presenting it as such feels like one is doing a serious study of industrial anthropology by a close viewing of Gung Ho. Michel Baudin says this best: “Countries don’t have production systems, companies do”:

“What does the Volkswagen diesel emission scandal say about eyeglass lenses and telescopes made by Zeiss or A320s assembled by Airbus in Hamburg? Nothing. Factories for these companies are all located in the same country but a lapse by one is just that, and the Wall Street Journal did not publish articles suggesting that it made a statement about German industry as a whole. When it comes to Japan, however, this is exactly what they are doing with this article, assuming there is such a thing as “Japanese manufacturing,” which is blemished by the misbehavior of any Japanese company.

What top management recently did at some Japanese companies does not invalidate the ideas of managers, engineers and production operators at other companies in the past 70 years. And whoever thought ideas were valuable just because they came out of Japan was as misguided as the authors of this Wall Street Journal article.”

That said, a more productive response to an article like this might be to reflect on the questions it raises rather than try to correct or defend.

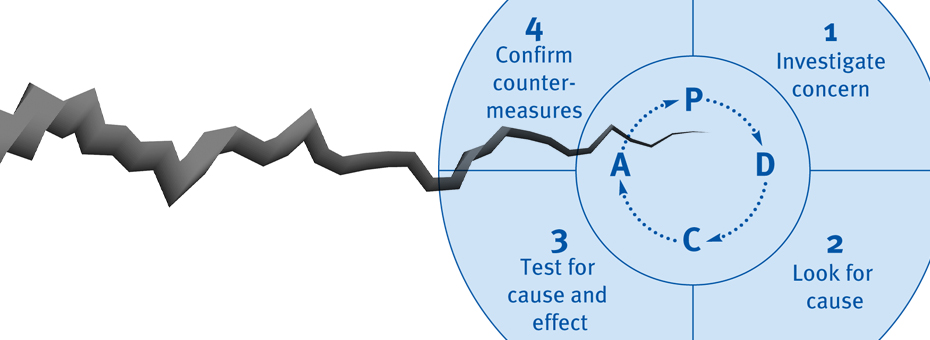

One question the article raises is whether a system like this can thrive based only on front-line workers having the authority to pull the andon. This would imply that TPS or lean relies on merely one set of practices. Yet as Dan Jones notes, lean is, indeed, a complete SYSTEM of management, and a healthy gemba cannot function without proper leadership:

“The Gemba model was never just about getting front-line staff to eliminate waste through continuous improvement. Their capabilities only grow when they are actively supported by leaders, who also remove obstacles to further improvement and who feedback the results of problem-solving int next-generation products. If these lessons are ignored then Gemba improvements run into the sand. It seems like many Japanese firms did not fully understand these lessons – indeed there has always been a big difference between the Toyota’s and many other Japanese firms. Indeed Toyota slipped up and the Gemba focus was lost sight of several years ago – and their response was to redouble their efforts to build awareness of the basics – and learn from them in learning how to scale up new innovative technologies – as they are now doing with mobility. As we continue to discover there are many significant layers about what makes people-centric systems work far better than people-free systems that are still common everywhere.”

More importantly, an article like this raises the key question of whether the failure of several bad actors invalidates the model itself. Hello, confirmation bias and small sample size (two heuristics that are themselves anathema to lean thinking.) In his article, “Is the gemba-management model cracking?” Michael Ballé praises the piece for tackling the uncomfortable truth that while it’s one thing to tout the power of TPS/lean, it’s entirely another to actually practice this with integrity and consistently at the gemba. That perhaps the model is valid yet that people have forgotten the basics:

“The point of an ideal is that it’s hard. The issue is not when it’s easy to apply the ideal, but when circumstances all push towards compromise and cut corners. As we also know from social psychology, the rot sets in one compromise after the other – each cut corner makes the next one more acceptable, easier.

There is a spiritual dimension to making the model work – the relentless passion to go to the gemba and both challenge teams and listen to their concerns and, most difficultly for human beings, to accept unfavorable information rather than dismiss it and shoot the messenger, and delve deep into that to find actual countermeasures rather than whitewash. Of course, it’s never easy – it’s just not the way humans are built. But that’s the point of it: to try and be better.

Of course, the model is cracking. It’s always cracking. The model is there to make you more competitive and that’s hard. That is precisely the point. The question is: “is the gemba and kaizen model wrong?” To answer that question we would need more than a flurry of high visibility isolated cases and some understanding of whether Japanese quality is faltering as a rule in manufacturing products. From my own equally limited window of knowing people who compete with Japanese companies, I don’t see it.”

So ultimately the best way to see pieces like this is as teaching moments—yes, the world outside our lean citadel frequently gets lean “wrong”. But lashing out at these recurring examples as misguided may be a case of rushing to solve the wrong problem. What problems does this article reveal? What are the real teaching opportunities here?