Dear Gemba Coach,

I’ve been working on lean projects for years and my CEO has now asked me to act as the lean sensei for our company. Is there a way to define standard work for senseis?

Ah. How old are you? I’m not being flippant. I’m told that the literal translation of sensei is “person born before another.” “Teacher” doesn’t quite capture it, and neither does “master” or “guru” as “sensei” has no connotation of telling you how to live your life, sensei-ing is very topic-specific (sensei are also known for their weird personal quirks outside of their professional expertise domain). For instance although I aim to be a sensei one day, I don’t consider myself one – after all, at 50 I’m still young for it and I only have 20 years of lean practice, not the 30 it supposedly takes to become a TPS sensei – a number I’ve heard several times from Toyota sensei.

What’s this about the grey hair? The key quality of a sensei goes beyond knowledge, experience or expertise – it’s about wisdom. Wisdom is this ineffable skill to use knowledge, experience, and expertise to come up with insightful, sensible, smart ways of unraveling tricky issues in their specific material and human context. And this kind of good judgment grows with age, no two ways about it (as does folly, actually, on topics where people refuse to see the world moving further away from what they know).The key quality of a sensei goes beyond knowledge, experience or expertise – it’s about wisdom, this ineffable skill to use knowledge, experience, and expertise to come up with insightful, sensible, smart ways of unraveling tricky issues in their specific material and human context.

Do you really get wiser with age? The answer is: you can. New research shows that high working memory capacity, which is the key to solving narrow, well-defined problems, does not necessarily contribute as much to problems requiring insight.[1] As you get older, you can either refuse to get to grips with it and become obsessed by the fact that you’re no longer who you used to be or, conversely, become much better at accepting reality and facing it with equanimity, a core skill for any sensei.

The senseis I’ve seen on the shop floor share this ability to not worry too much about the current burning fire (which might seem like the end of the world to the manager having to put it out) but remain focused on the fundamentals that will make the situation better, eventually. In this sense, the sensei is the embodiment of lean thinking in terms of building capabilities rather than working around short-term problems (solving short-term problems is part of growing competencies and, over time, building capabilities).

Karate Kid Lessons

Standard work for sensei? I have to confess I’ve never looked at it this way. Let’s break down the components of standard work:

- A clear vision of the quality of the outcome: The sensei keeps focused on growing the person so that they resolve a typical situation with greater autonomy by personally mastering typical countermeasures: you develop the person, not fix the problem.

- Fundamental sensei-ing work elements: Taking people to the gemba, pointing to normal vs. abnormal, asking “why,” pushing for better visual management, hinting at lean principles, and giving specific learning exercises.

- Basic sensei skills: Seeing the link between the detailed problem and overall performance, grasping what’s in a person’s mind (how they see the situation from their perspective and tunnel vision), and tailoring the progress exercise to the person’s current knowledge and developmental zone (too hard and they won’t get it, too easy and they won’t make the effort).

- Deep knowledge: Understanding how the business works as a whole, what are the current challenges, how work is done in detail and knowing inside out the lean tools and how the principles apply in specific, given situations (no wonder it takes 30 years).

On the gemba, the sensei’s job is very similar to a sports’ coach:

- See which performance needs to be improved,

- See what the learner is getting wrong in the way they go about their work,

- Diagnose the basic skills gap, and what specific skill the learner has to develop to succeed – which might be away from the symptom, such as one muscle one has to develop to do something else,

- Figure out the right exercise for the learner to develop this skill,

- Steer the learner’s insights as they practice the exercise for them to develop deep understanding as they learn-by-doing.

In the lean tradition, these exercises mostly fall into three categories:

- Visual management: Specific stuff you can do on the gemba to better visualize the flow of work and reveal problems as you work.

- Pushing for immediate kaizen: Point to a problem, try immediately something small, think about what happens, move on the next improvement.

- Asking “why?”: Deepening observation and discussion by questioning, listening, and questioning again.

Learning, however, is a collaborative practice. In the words of the archetypal sensei Mr. Miyagi from the cult movie Karate Kid: “I promise to teach karate to you, you promise to learn. I say, you do, no questions.” The key success factors of any sensei/learner collaboration are (1) the wisdom of the sensei’s judgment in context, (2) the sensei’s mastery of the tools, and (3) the relationship between the sensei and the learner. This relationship, in particular, is both weird and specific as senseis tend to be dogmatic to the point of dictatorial in the training routines, but supportive and outright friendly in everything else. Karate Kid captures this as well as the learner, Daniel tells his sensei “You’re the best friend I ever had,” to which the sensei answers (with proper Hollywood Japanese accent) “You pretty okay too.” And, by the way, on the wisdom front, Mr. Miyagi doesn’t teach Daniel just how to punch or block. His core topic is balance.

Grunts and Nods

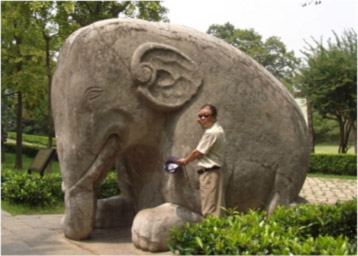

We need to add relationship building to the list of impossible skills that make a sensei. Wisdom, detailed knowledge, relationships… and role modeling. Here’s a great photo of Toyota sensei Joe Lee “staying foolish,” touching a part of the elephant to remind himself that what you see is never the full picture. As he reminded me, a Confucius saying goes: “When three men walk together one of them can always learn something from the other two. He can profit by the good example of the one and avoid the bad example of the other.” Who you choose to listen to is the first set in wisdom-building.

If you’re serious about developing sensei-ishness I would argue for worrying less about “sensei standard work” and more about your own self-reflectiveness. Personally, and again, I don’t claim to be a sensei (to paraphrase St Augustine: Lord, grant me sensei character, but not yet!), these are the questions that keep bugging me after I’ve spent a day poking at things at the gemba and arguing it out with the guys (I’m personally a far cry from the poker-face senseis of my youth where you interpret the meaning of their grunts and nods):

If you’re serious about developing sensei-ishness I would argue for worrying less about “sensei standard work” and more about your own self-reflectiveness. Personally, and again, I don’t claim to be a sensei (to paraphrase St Augustine: Lord, grant me sensei character, but not yet!), these are the questions that keep bugging me after I’ve spent a day poking at things at the gemba and arguing it out with the guys (I’m personally a far cry from the poker-face senseis of my youth where you interpret the meaning of their grunts and nods):

- Is this the right topic to be worrying about? Business is incredibly fluid and I worry less about the factors we see and are worrying about than those we don’t see because they’re harder to grasp. Undefined factors might be no less important. For instance, working with pricing you realize that the hard-to-grasp esteem function of a product or service from its reputation accounts for a significant part of the price. How can we tackle what we don’t know how to define or measure? The wisdom of focusing on this or that aspect of complex dynamic situation is always in question, as is our judgment when we act.

- How well do I understand the tool? There have been so many misunderstandings around Toyota tools that I always assume I’m misinterpreting to some extent, and teach my errors of understanding. I know it might sound silly, but 20 years down the line, I’m still collecting all the info and I can find on detailed tools, how they’re used and to what purpose. Looking back, most of my insights about lean have come from realizing I missed the point of this tool or that, not from high-level discussions of the lean “philosophy” (whatever that is). So tools, tools, tools.

- How am I getting along with the guys? I’m incredibly lucky inasmuch as most of the people I work with at the gemba have become personal friends, and remain so even if for whatever reason we no longer work together. Part of this comes from the mutual selection – when we don’t get on, we eventually stop – and part of it comes from the forging experience of facing tough problems together. Yet, making people see what they don’t see is never soft or easy, and there are many tense arguments along the way. I know people find me tough and often pushy. But I do worry about it constantly: how hard can I push? With what impact on the relationship. Surprisingly, a large part of my influence on senior executives is about slowing them down in what they push on their own staff to make sure we build mutual trust at the same time as a challenge for greater improvements. Kaizen will only happen within good relationships.

Push comes to shove, I’d say that the central skill to becoming a sensei is one’s own ability to continue to learn and desire to continue to become better at this open-ended, ever-mysterious thing called lean. The head of Toyota’s South African operations once told me a great story about his own sensei (who happened to be my father’s sensei – my sensei’s sensei, so to speak). They were visiting the Durban plant and some papers were flying in the African wind across the floor. When the sensei pointed this out, the manager (plant manager at the time) explained: “This is Africa! It’s the wind!” The sensei said nothing for a while and then replied: “Wind don’t make paper.” Now, that is senseihood.