In preparing for tomorrow’s Ask Me Anything session on The Lean Post, I was thinking of questions that I’m very often asked and are very hard to answer. Two in particular came to mind:

- Is there any other exemplar of lean companies than just Toyota?

- What is most misunderstood about lean thinking?

In fact, I feel these two questions are closely related. I believe that while Toyota isn’t the only lean exemplar out there, it still gives us a flawless example of what lean truly is – a definition that is so often misunderstood. Let us try to disentangle the matter.

There are many, many lean successes outside of Toyota, and contrary to other management movements, the lean field is very well documented both in its successes and failures (and everything in between) in books, journals such as The Lean Post or Planet Lean, blogs and so on. Toyota’s special place comes from the fact that the entire company was built on a specific set of values and operating principles we have come to call “lean” – no other enterprise has such a long, continuing and enduring history with it.

There are many, many lean successes outside of Toyota, and contrary to other management movements, the lean field is very well documented both in its successes and failures (and everything in between) in books, journals such as The Lean Post or Planet Lean, blogs and so on. Toyota’s special place comes from the fact that the entire company was built on a specific set of values and operating principles we have come to call “lean” – no other enterprise has such a long, continuing and enduring history with it.

“Leanness” (the Toyota Production System) is part of Toyota’s DNA, and still very much relevant today. For instance, when the company made an unprecedented $1 billion investment in artificial intelligence in Stanford and Cambridge, the head of this venture explained: “As extraordinary as the T.P.S. is, we believe it can be improved still further through the use of more data and more A.I.” This reveals two things:

- TPS is still very much at the center of how Toyota goes about doing things

- The spirit of continuous improvement is still very much alive and a core value

To a large extent I’ve long considered the “lean” movement as our response to Toyota’s challenge – to create more value and less waste by building better products and services to satisfy customers better through developing people – it’s a very specific challenge, and Toyota remains ahead of the curve in this respect. So yes, Toyota is relevant now and, in many respects, what Toyota did in the late Seventies and early Eighties when it codified the TPS is still relevant as well.

Which brings us to the point that I believe is the most misunderstood about lean thinking. Not only is “lean” not a “thing” in itself, but a response to Toyota’s challenge; Toyota’s challenge is not an absolute either. Rather, it is the constant search for competitive advantage. The promise of TPS within Toyota, or lean thinking outside of Toyota, is that of a relative edge on the competition, not a blueprint for design thinking on a new kind of company (the fact that this over time does produce a new kind of company obscures the issue, because you don’t get there by seeking a new design or organization, but by honing your competitive skills on a daily basis).

This is bred in the bone at Toyota. In 1950, Toyota was basically bankrupt as a result of post-war trouble and a violent labor dispute and strike. The banks that bailed out the company imposed a restructuring plan which involved laying off workers and separating Toyota Motors from Toyota Sales. Kiichiro Toyoda, the company’s founder, resigned in disgrace and tasked the company to “Catch up with America in three years. Otherwise the automobile industry of Japan will not survive.” It took them longer than three years, but catch up they did.

The question is how? If you are a small, parochial, provincial company in a dominated, saturated market, what can you do? Furthermore, having been badly burned from their near-bankruptcy episode, Toyota executives committed to the additional constraints of no outside financing and no more strikes. What they then determined to do, which later led to the full TPS, was to seek competitive advantage through internal operation effectiveness rather than playing the game the way it was played by all competitors. This led them to seek two very clear industrial strategies:

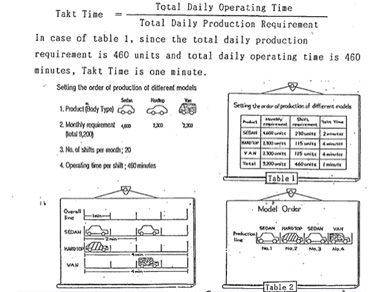

Rapid introduction of new products and a wide range on the same production equipmentThroughout the Sixties the competition for the Japanese passenger car market was fierce between Nissan, Mitsubishi, Mazda, Honda and Toyota. The name of the game was introducing more models faster, and Toyota worked very hard at designing new cars that could be built on existing production lines. This would allow them to increase production of new models without having to commit to new facilities before knowing if the demand could support the volume needed for payback. This led to “just-in-time,” a radically different engineering, production and supply chain industrial system that built flexibility into the system from scratch, and put pressure on the market by allowing a wider range without carrying the overcosts of this wide range.

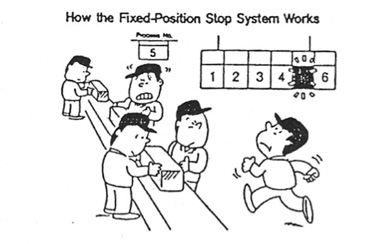

Rapid introduction of new products and a wide range on the same production equipmentThroughout the Sixties the competition for the Japanese passenger car market was fierce between Nissan, Mitsubishi, Mazda, Honda and Toyota. The name of the game was introducing more models faster, and Toyota worked very hard at designing new cars that could be built on existing production lines. This would allow them to increase production of new models without having to commit to new facilities before knowing if the demand could support the volume needed for payback. This led to “just-in-time,” a radically different engineering, production and supply chain industrial system that built flexibility into the system from scratch, and put pressure on the market by allowing a wider range without carrying the overcosts of this wide range. Built-in quality to design more robust products than the competitionIn the mid-Sixties, Toyota leadership focused heavily on quality by introducing TQC and receiving the Deming Prize in the 1965. Progressively, the focus shifted from quality through inspection to built-in quality by generalizing control points throughout the process, starting with engineering.“Peace of mind” became a core benefit of Toyota cars, the feature customers seek and can’t find elsewhere to the same extent. A wide range of models combined with superior quality and standard options (partly to make assembly simpler) at a reasonable cost put the pressure we know on world markets when Toyota moved out of Japan and started exporting in earnest. Toyota recently released a new “Toyota New Global Architecture” aimed at further improving plants’ output and flexibility through engineering strategies to handle variety whilst keeping CAPEX in check.

Built-in quality to design more robust products than the competitionIn the mid-Sixties, Toyota leadership focused heavily on quality by introducing TQC and receiving the Deming Prize in the 1965. Progressively, the focus shifted from quality through inspection to built-in quality by generalizing control points throughout the process, starting with engineering.“Peace of mind” became a core benefit of Toyota cars, the feature customers seek and can’t find elsewhere to the same extent. A wide range of models combined with superior quality and standard options (partly to make assembly simpler) at a reasonable cost put the pressure we know on world markets when Toyota moved out of Japan and started exporting in earnest. Toyota recently released a new “Toyota New Global Architecture” aimed at further improving plants’ output and flexibility through engineering strategies to handle variety whilst keeping CAPEX in check.

We have seen what Toyota’s competitive pressure on market range, pricing and quality has done to its competitors in the U.S. first, then in Europe. More recently we have seen the VW debacle as it tried to cheat its way out of Toyota’s competitive pressure on fuel efficiency, and the mind-boggling overcost this will create for the company.

Many lean thinkers I meet tend to discuss “lean” as a set of organizational design rules. They seek a model of efficiency, which can be applied to redesign their companies. My hunch is that this misses the profound lesson Toyota can teach us: relentless continuous improvement is a competitive edge that we can use to shape markets in our terms and bring competitors to compete on areas where we have the operational advantage.

There are no obvious big bang solutions to any large-scale problems – only many small steps in the right direction. Toyota’s deep lesson of improving technical processes everyday by working more mindfully and thinking more carefully about the decisions we make is, I believe, a proven way forward, if we abandon seeking full design solutions and submit to the discipline of daily kaizen to reach large-scale goals.