Dear Gemba Coach,

In your previous column you stated that VSM can be misleading. I’ve been using VSM for years to improve process efficiency – what can be wrong with that?

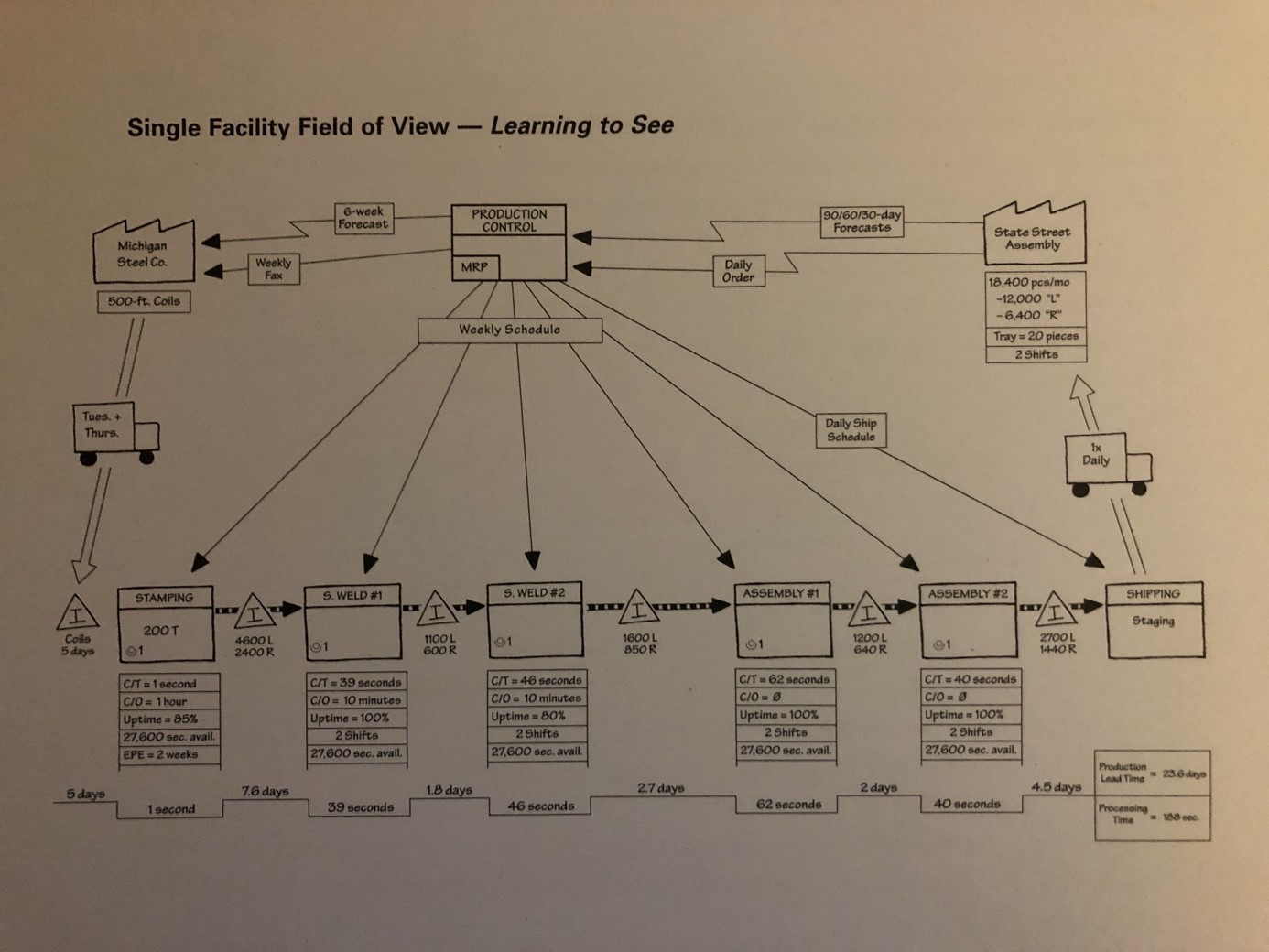

I’m not sure wrong is the right term. Misleading, yes. To go into this we must be willing to take a step back. Let’s use the map as our gemba and look at a VSM (from the workbook Seeing the Whole):

The stated goal of this analysis is to evaluate processing time, 188 seconds, over production lead-time, 23.6 days. The implicit goal is to improve process efficiency: the ratio of processing time to production lead-time.

This is not a strategic issue, this is an operational issue. Product/process decisions have been taken, now the challenge is to make it work by improving the flow. And it’s a good idea – but hardly a game changer.

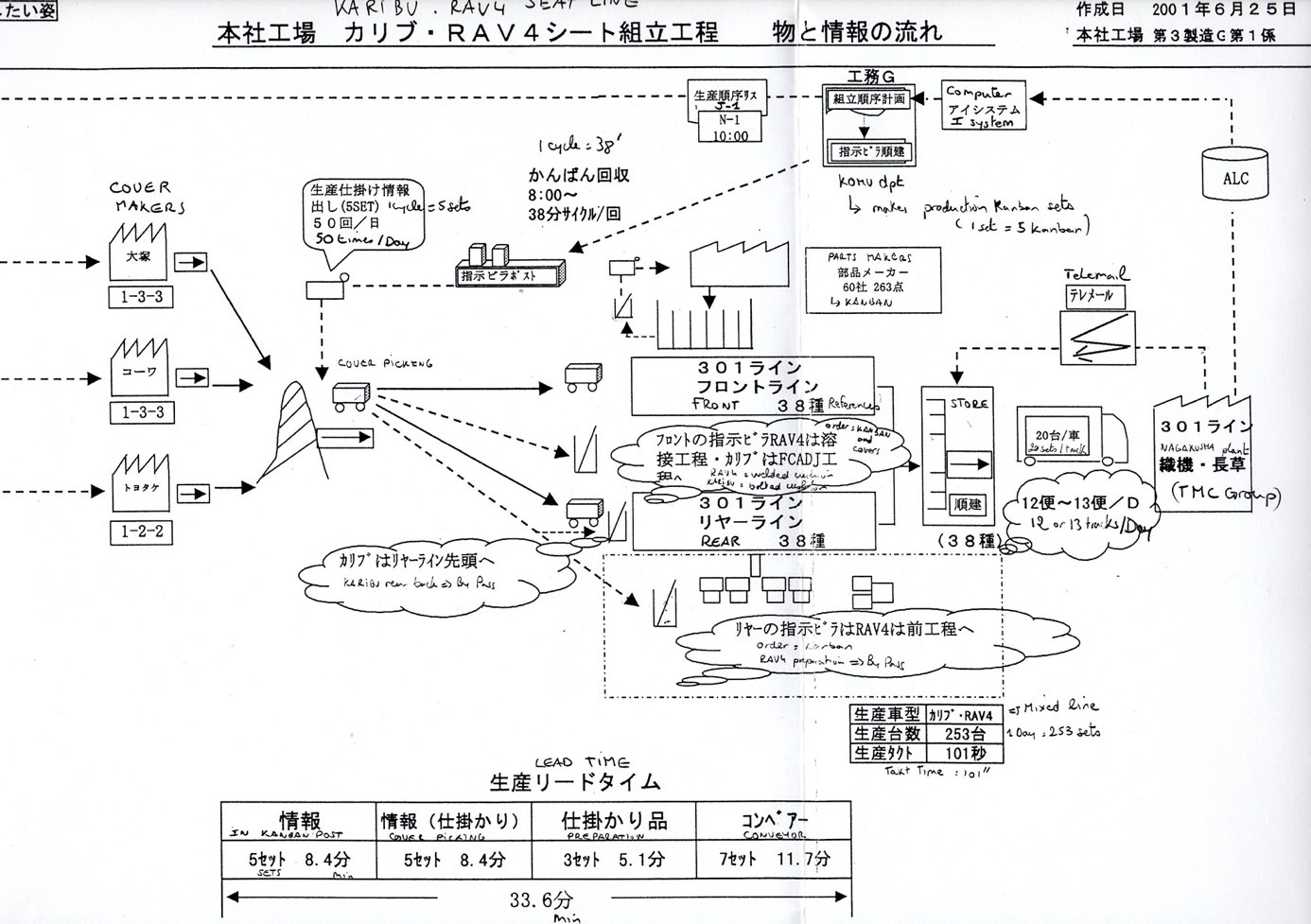

Now let’s look at the original Toyota tool, the MIFA (Material and Information Flow Analysis):

This is a lead-time analysis that looks at the logistics of flowing 38 types of seats through the same process. How is this strategic?

Lean is not about just improving flow – the aim is to improve value – better quality over lower total costs.

Increasing value starts with reducing costs, the real costs each single product has to bear:

- The cost of the facility it’s built in, with all of its processes to maintain and people to pay

- The cost of direct labor that goes into making the product, with all the corrections and controls needed to make a good product

- The cost of materials that go into the seat, with all the scrap and defectives that need to be disposed of

The strategic way to reduce overall costs by better utilizing the facility is to be able to build a wider range of products over the same equipment. In that way, market variations (selling more of A than B today, but more of B than A tomorrow) can be absorbed and the cost each single product bears is minimized.

Ask the Strategic Question

This, of course, is very hard to do. The simplest way to run operations is to break down the manufacturing process into separate operations and to dedicate a process to a single step and a single product, and then put the necessary logistics in place to move semi-worked stuff from one place to the next – the reason VSMs always look so impressive: processes are broken down in zillion steps with inventories between them.

The strategic lean question is: how do we get one more product into the same facility – without increasing our lead-time? This, is the game changer.

To do this, we think the other way around: how can we decrease existing lead-times to make room for more variety. Toyota has been working on this for a long time, and from doing MIFA maps again and again, has concluded that lead time stems from four typical difficulties:

- Large lot size

- Poor logistics

- Complicated flow

- Weak belief in takt time

To be able to build more products on the same equipment, the first obvious problem is being able to change from making product A to product B. In an ideal world, this change should happen after each product produced – but clearly this is rarely possible (think of a stamping press), so there is a constant fight to reduce change-over time in order to reduce batch sizes.

Batch size is not the only cause of inventory in the process. Logistics matter. The more frequent the pick-ups, the lower the inventories at each point, even if the technical process is not fully flexible. The precision and frequency of logistics puts pressure on the flexibility of processes. But logistics is … logistics. It has to work every minute and something always goes wrong, so keeping logistics working like clockwork is a daily challenge. One needs to be obstinate about picking up every part every 15 minutes.

There is nothing wrong with using VSM to improve process efficiency – it’s a good thing … but is not a game changer – it doesn’t change the competitive positioning of the company.If you try to manufacture several products in the same facility, you’ll find that they don’t always go through the same intermediate processes and so internal flows get very complex and mixed up. The second challenge is to 1/ design different products, so they can be assembled in the same sequence, on the same equipment and 2/ redesign machines so that they can be smaller and fit in sequence in one cell. This second challenge affects both product design and manufacturing engineering.

Filling a facility with useful work also requires a strong determination to produce at the same pace as sales – produce only what customers have bought. The temptation will always be there to make our own schedules in order to make it easier for production, stuff it all in inventory and wait for customers to buy.

The MIFA tool is not a map of process flow – it’s a map of inflexibility points in the facility, a very different outlook.

It’s strategic because flexibility affects product and process (technical processes, not sequences of who does what) decisions in ways that require leadership commitment to what we intend to do to improve value. It reverses the thinking.

From:

Make all the product allocation to facilities decisions, end up with a sub optimized production base, and then use VSM to try to fix it by improving flow and process efficiency.

To:

Constantly work at making facilities more flexible in order to make the strategic decisions of what product goes where and which processes we need to invest in.

VSM? Meh

The former is the traditional “strategic clarity/execution capability” mainstream frame: take all decisions on paper at the top, and then “make it so” as best we can at the workplace. The latter is lean thinking from the gemba, improve capabilities daily in order to open up the field of strategic options “wide line-up/controlled cost base”.

There is nothing wrong with using VSM to improve process efficiency – it’s a good thing, and that’s what the tool is for. What I’ve discussed often is that it does make things better, but is not a game changer – it doesn’t change the competitive positioning of the company. The process you’ve improved is likely to both revert to its previous stage at every new product introduction, and improving the flow and process efficiency does not lead to changing the thinking about product line-up and product and process development. How does that sound?