This brief video offers a quick overview of how and why this essential practice helps lean practitioners see and improve their work processes. (Read the lightly edited transcript, below.)

Hi, I’m Jim Womack, president of the Lean Enterprise Institute. I wanted to welcome you to this value-stream mapping workshop and share with you a little background of where this came from and why I think it’s so terribly important. The ideas that you’re going to learn about are not new. In fact, they were mostly invented by Henry Ford in the early 20th century. In 1913, at Highland park, he opened a car plant for the Model T, which actually used all of the ideas that we now talk about in the context of value-stream mapping.

Ford Invents Flow Production

Ford had grown up in a world where you put processes in different places, and the product went to the process. Things moved all around. They didn’t go very quickly. So, lots of big batches, lots of stopping and starting. And at Highland Park, Henry Ford had a fundamentally revolutionary idea: Why don’t we line up the activities in process sequence so that the product goes smoothly from beginning to end?

Now we know about the assembly line. That’s really not the great breakthrough that Ford made. Though, that’s a wonderful breakthrough. But what Ford made his breakthrough in, more importantly, was in the actual fabrication steps: casting, machining, painting, welding — where he lined up all kinds of technologies that didn’t normally then, and don’t normally now, live together, into one continuous sequence to create flow. And he talked about flow. He called his system flow production back in the early days.

The problem was that he just had one product, the Model T, that came with no options and came in one color. And as long as that’s all he had to make, it was very easy to introduce continuous, smooth flow. As time went on, the industry had a wide variety of products, lots of options, lots of colors, and customer demand went up and down and up and down, and gradually Ford and other manufacturers abandoned the original flow ideas, which were rediscovered after the second world war by Toyota.

Ohno’s Advances Flow Production

Taiichi Ohno, the fellow who put the Toyota production system together, always said, “I learned everything I know from Henry Ford, except I found a way,” said Ono, “to do it with high variety and low volume. Ford can only do it with low variety and high volume.” So, how to create flow in a steady pull of the customer, a voice of the customer all the way through the production system, with high variety, low volume — that was the real challenge. And that’s what Toyota found out how to do.

Toyota people use the method that you’re going to hear about value-stream mapping. To them, it’s just natural; it’s like breathing. For us, because we’ve not used this language, it seems a bit strange. The idea is to take a product family and write down all the steps, from start to finish, for either a component or the whole product.

Using VSM to Achieve Flow

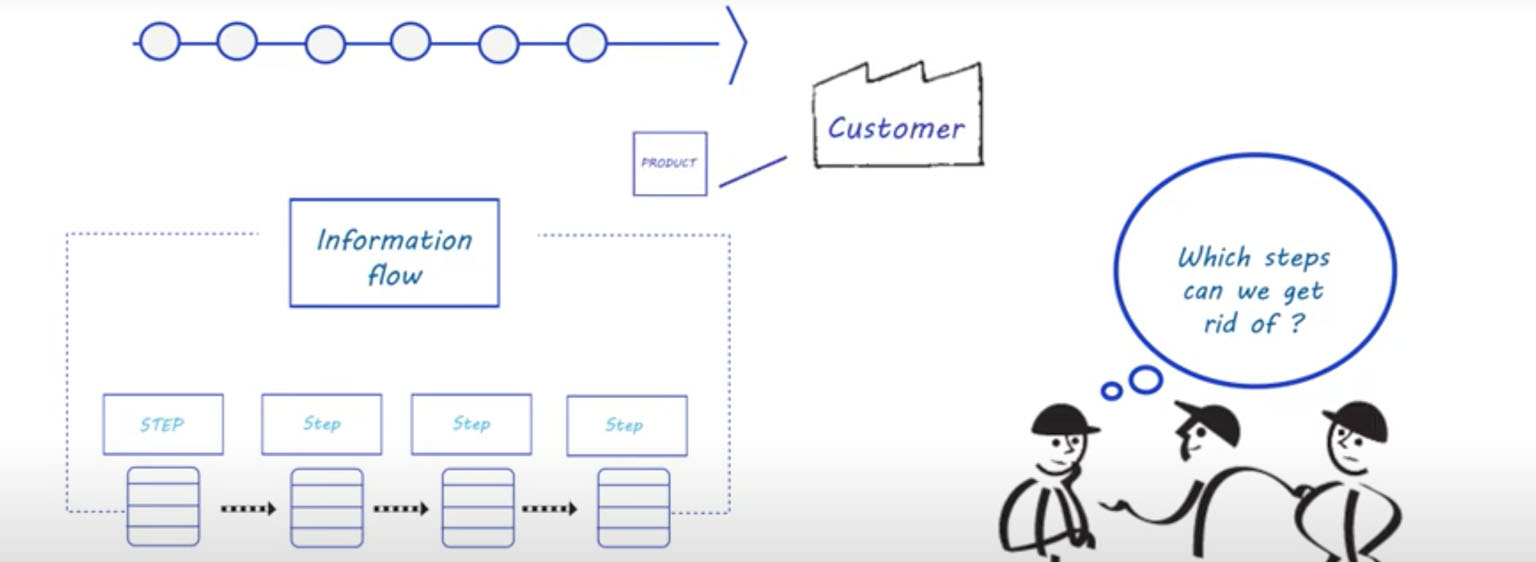

You could draw a map all the way from raw material to the customer, but let’s be practical and just start at the plant level. Write down all of those steps and ask a very simple question: Which of these are waste? It turns out that most of the steps were waste. And which actually creates value that the customer would be willing to pay for?

Then when you’ve written down those steps, you need to write down the information flow. You’ve got steps, physical steps, going across the bottom of the map. You’ve got information flow across the top of the map. You put that together. And, when you’ve done that, you have a complete map. Then you ask some very simple questions: Which of the steps can we get rid of? And of the steps that remain, how can we do them in a continuous flow, so the product goes smoothly and only — only — when the customer wants it, at the pull of the customer.

Learning to See

So this is a method for drawing yourself a map so you can see that. As we say, so you can learn how to see. So many managers, good managers, hardworking managers, and workers — hardworking workers — are, in fact, blind. They’re looking at all the wrong things. They’re looking at the machine. They’re looking at the organization. They’re looking at the plant, the facility, the walls — we need to learn how to look at the product. The customer is only interested in the product.

This is the tool that permits you to do that. It’s a tool that you need to learn, that all of your coworkers need to learn — no point in learning a language that only you can speak. The whole point of a language is everybody speaks it.

So this is the start; this is a course that will get you going, your first course in this new language. I guarantee it will change your life. It’ll change your business. If we all do it, it’ll change the world. So let’s get started.

What is your source for Taiichi Ohno’s quote “I learned everything I know from Henry Ford, except I found a way,” said Ono, “to do it with high variety and low volume. Ford can only do it with low variety and high volume.”