A consistent struggle I hear from organizations is the difficulty to sustain improvements that have been made at the gemba. In the lean world, when this occurs we often turn to establishing daily management systems (daily huddles for example) that are meant in some ways as a monitoring mechanism to the improvement work. This is good. But it does not truly address the underlying challenge that we have no true mechanism to rapidly instill daily continuous improvement (kaizen) into the workplace.

While in Toyota and since then, I been exposed to a specific methodology called Jishuken, whose primary purpose is just that – to build front line capability to sustain continuous improvement (See Matt Savas’s previous post). Furthermore, it compresses the lead time in capability development through cycles of intensive team learning and continuing on your own what has been learned as a team.

As Matt explained, based on what we saw at Kyushu, Jishuken is a structured multi-week to focus the organization to improve the gemba based on a defined business target and with clear Team Member development needs defined.

Jishuken can also be a powerful methodology to challenge an individual’s thinking on how we look at work and how we learn through doing. But most importantly, how we respect the value creating work that people do, which leads to deeper understanding, with real humility, our limited ability to impact the work of the value creator. Rather than philosophizing about it, let me share my own Jishuken experience. An experience in humility that I carry with me to this day.

When I joined TSSC (Toyota Production System Support Center) in October of 1994, I was immediately thrown into uncomfortable situations where I needed to learn how to learn differently. I wrote about one of those situations in my last post, Cardboard, Duct Tape and String – the Do-First Mindset.

There were a bunch of people like me at TSSC, all learning under Japanese Managers with TPS skills, sent to the U.S. to help Toyota’s North American supply base. One of those suppliers was a medium-size plastics manufacturing company located outside of Lexington, KY, and set up to supply Toyota in the Georgetown plant.

The General Manager of TSSC at the time, Mr. Ohba, decided it would be good to send the new TSSC guys all together to transform the shop floor of this company. He pulled about 10 of us into a room and explained that over the next two months we would spend time transforming the shop floor through a Jishuken activity. We were organized in three teams: one team focused on the overall production system, transforming the plant from a push system to pull, and two teams focused on improving the work in individual assembly cells.

With only six months into my tenure at TSSC (though sx years in Toyota in an administrative job), I was put in charge of one of the teams. The plastics company also assigned four people to join us in the effort. My team studied the assembly cell that built components for the Avalon.

Each of us was assigned a team member and asked to study the work of that team member. What was the work? What were the steps in which it was performed? Where was there waste?

An initial analysis revealed that, though 10 people worked in the cell, only 6 were needed. So we worked late nights every night that week and in some of the following weeks to get the number down to 6. And we did!

A big report-out was planned at the end of the activity with the Founder/CEO of the company and Mr. Ohba. We worked late the night before and thought we had a great story to tell.

The following morning we shared our analysis and results with everyone. I reported for our team and was asked many questions about our numbers and our approach. We took a coffee break and everyone left the room.

When we came back, Mr. Ohba only said only four words to the three teams: “Do it over again.” That’s it. Not, “good effort”. No commentary on what we’d done. Then he left.

I was floored. The team had worked so hard and we’d achieved our target, but this was the conclusion? Really? So I went to our Manager (another Japanese Manager) and asked why. He said that in reality, we had only rearranged the work elements and not actually improved the work of the people. Yes, some waste of walking was removed, but the Team Members still had many struggles in the assembly operation that were not addressed.

Then he asked me: “What is the purpose of Jishuken?” I thought for a moment and said: “To realize a business benefit for the company.” He said, “You see, this is why you need to repeat this Jishuken. You haven’t learned the purpose.”

Then he walked away. And I was left standing, waiting for an answer that never came.

We went back for several weeks, focused on the team member work more intently, engaged with each operator, and helped them make their work better.

Yes, Jishuken is normally an intensive, week or weeks-long activity with a defined target to achieve a goal. And to develop capability. But if that is all it is about, why do they call it Jishuken or “SELF-learning”?

In the end I learned a lot about myself (SELF – Learning): how I approach work, support value creation, and stay focused and humble in the presence of such work. This is the Self-Learning implied in Jishuken.

I was recently asked “What’s the difference between jishuken and what many consulting companies sell as weekly improvement events? Good question. Well, I don’t know the content of what everyone is out there selling, so I can’t speak from real knowledge. But if the idea is to sell an “event” rather than establish a structure of self-learning in the organization, it seems like the wrong direction to me.

As another point of reference, I was having a discussion recently about the meaning of Jishuken with another former boss of mine in Toyota. He said at one point he was meeting with a pretty famous Japanese TPS guy by the name of Mr. Ikebuchi (worked for Taiichi Ohno). Mr. Ikebuchi asked him the same question I was asked years ago: “What is the purpose of Jishuken?” He tried to answer, saying things like business results, people development, etc. (this guy was no slouch now mind you – 30 years doing TPS in Toyota).

Mr. Ikebuchi kept saying No. Maybe because my boss had 30 years’ experience, he finally graced him with an answer: “The purpose of Jishuken is to do more Jishuken.” Huh?

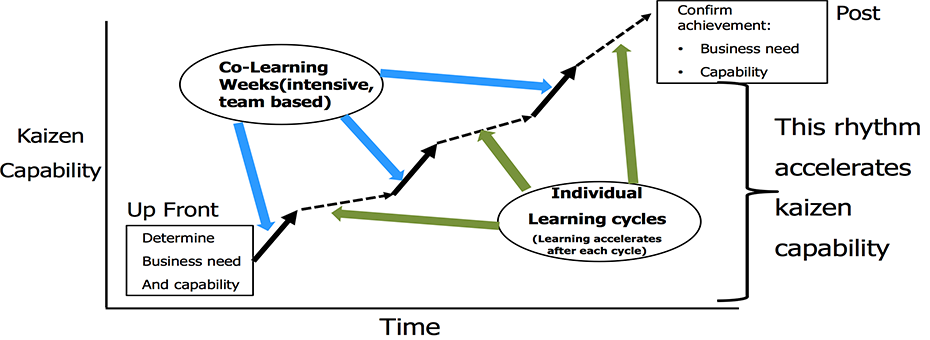

Think about it for a moment… This intensive effort to drive individuals and the organization to a higher level, if done right, should push everyone to do more and more, improving in cycles of intense, focused effort with something that leaves a strong residue of kaizen spirit behind and allows the company to sustain. Then it’s ready again for another Jishuken. It becomes a driving force to innovation in the organization by pushing people to higher and higher capability.

Because it forces you to consider deeply how you can make the work better for others and this pushes you to understand your own capabilities (or lack thereof) to accomplish such a goal. In fact, how can we be so presumptuous that we know how to fix someone else’s job who does that difficult work day to day? The only way is to step inside their shoes and try the job and closely observe how they perform the work. This requires ongoing cycles of learning.

Otherwise, it’s an exercise in hubris.

Lean Leadership Learning Tour

Go beyond theory—see lean leadership in action.