In this monthly feature highlighting the essential lessons of specific LEI titles, Michael explains what this 2014 book introduced that was both new–and eternal.

The “respect” dimension of lean is hardly new. The very first paper published in English on the Toyota Production System back in 1977 describes it as having two major features:

- Just-in-time production: only the necessary products, at the necessary time in the necessary quantity are manufactured, and the stock on hand is held to a minimum.

- Respect-for-human system: workers are allowed to display their full capabilities through active participation in running and improving their own work.

The meaning of the term “lean” has been evolving since it was popularized as a more generic label for the Toyota Production System. In the early days, just-in-time was put at the fore of the message. Since then we’ve come to realize the importance of respect-for-people to lean thinking. Whereas at first lean was essentially about kaizen workshops to improve flow, long ago we saw that shift from one-step improvement to continuous improvement. Evolving from on-going training to problem-solving was also a core element of lean thinking. At that time we had not looked at lean starting with “respect” and figuring out how the rest of lean thinking looked from this point of view.

We asked: is there a lean leadership behavior people could aspire to in order to deliver lean results?When my father/co-author Freddy and I started having this discussion, just after publication of The Lean Manager, we kept coming back to the basic fact that although Freddy tried hard to develop all of his direct reports to lean thinking, a few “got it” and many didn’t. Later on, after Freddy retired, we designed lean programs to help other companies based on his experience. We tried to improve the “got it” ratio without, I have to confess, much visible success. There always seemed to be two or three in ten execs who “got it,” and as a result would learn to redefine what performance meant for the group; this and would be followed by another five or six, who would then apply tools to catch up, leaving an unavoidable two or three resisting new ideas to the bitter end. Overall, this effort delivered visible results but had the familiar weakness of being quite fragile because the entire program would rest on the energy and wits of a small number of people.

I’m at the Gemba, Now What?

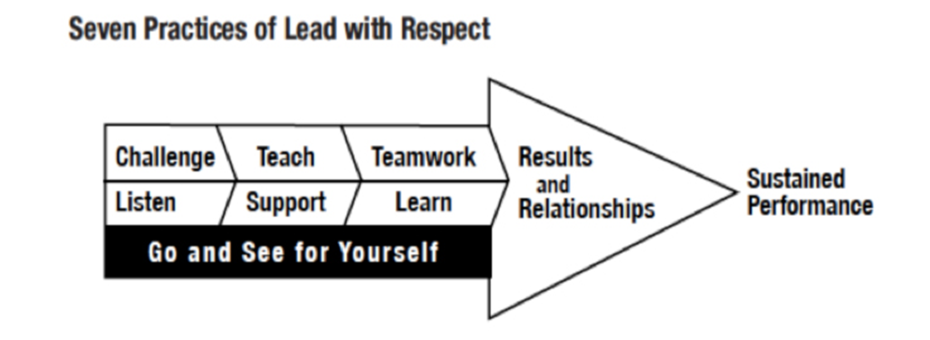

Looking at it case by case, we asked ourselves what distinguished the leaders who “got it” from the ones who didn’t, and came to realize we were asking the question of a leadership standard: is there a lean leadership behavior people could aspire to to deliver lean results? For years, we’d been saying that the first step to lean thinking was to “go to the gemba and see” – but what, exactly, was a leader supposed to do once at the gemba? (We realized that many leaders shunned the gemba because they felt uncomfortable about their role on the shop floor in front of workers’ comments and occasional demands.)

Based on Freddy’s first-hand experience as a supplier to Toyota, we started by interpreting “leadership” as a commitment to achieve objectives through the development of each individual person, as opposed to with the development of people. We realized that developing people was the first imperative: results were to be sought by people development first, not by command-and-control that incidentally develops people. This belief led us to define the main goals of leading by going to the gemba:

- Getting people to agree on the problem before arguing about solutions by focusing on facts and their interpretation – and making an effort to listen to frontline people’s opinions and hear their concerns.

- Day-to-day on the job development through the discipline of pull (JIT and jidoka) – every one learns by solving problems within the job itself by (1) learning standards and (2) solving problems.

- Intensifying collaboration within teams and across functional boundaries by learning to solve problems with colleagues – and thus to improve overall processes through better coordination.

- Encourage initiative and creativity from employees by supporting them in improving their own workplace through suggestions or kaizens.

In the numerous versions of the early drafts (thanks here to our editor, Tom Ehrenfeld, who kept challenging us on the topic), we realized that —

- The leaders who “got it” learned to learn: in supporting kaizen and listening to people they also changed their own understanding of what was important and what less so, occasionally opening the way to true innovations.

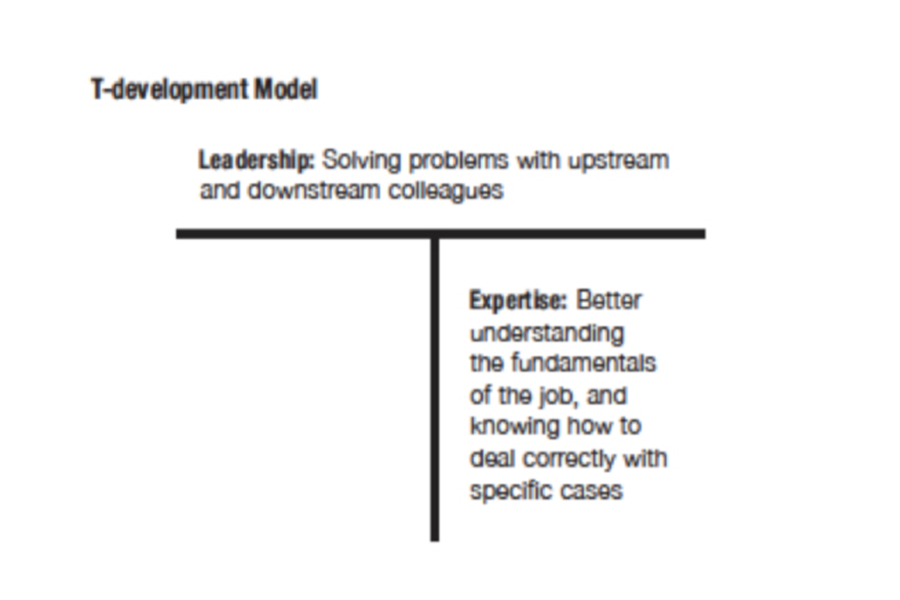

What we then needed to do was to describe more precisely what, exactly, we meant by “developing people” – and the people development underlying Toyota’s approach. Thanks to Toyota Way’s Jeff Liker’s generous help, we came to refine the “T-development” presented in the book:

Finally, by looking back on lean leaders actual behavior at the gemba, we defined a behavioral management model based on improving both the results and the relationship, which is now presented at the beginning of the book as the seven practices of Lead With Respect:

Boring Text Is Muda!

We are the first to admit that these ideas and practices have been at the core of lean practice since the very start: many of these principles can be found inThe principles and practices presented here are specific to lean, and the underlying motivational model is a blend of modern psychology research and lean experience at the workplace. Taiichi Ohno’s writings. What we have hoped to do is focus on a “people first” look at lean, and describe the principles and tools of the people aspects of the lean tradition as precisely as we could .

We believe these core ideas have been present in the TPS tradition, but rarely highlighted as such; and have not hitherto been published in a consistent form. Lead with Respect presents what we hope is a full, self-consistent theory of HR that breaks away from both traditional Taylorist and the Human Relations schools. The principles and practices presented here are specific to lean and the underlying motivational model is a blend of modern psychology research and lean experience at the workplace – this part, for sure, is new.

In the many years we’ve been writing lean novels, Freddy and I have tried to present lean from a fresh perspective each time. The Gold Mine is an introduction to lean thinking and tools in a practical context, with a strong link to the business situation. The Lean Manager is a presentation of a full lean system as a complete way to run one’s business. Lead With Respect portrays on-the-job behaviors of lean leaders which can be learned through practice to fulfill the promise of lean by aligning the company’s success to individual fulfillment. A rather lofty aim, which we tried to make as lively as possible through the lives of the characters (boring text is Muda!) to make it a good summer read as well!

*****

What to do next:

- Michael Balle’s third lean novel Lead With Respect delves deep into the topic of how lean managers can adopt tangible ways of unleashing the human potential for growth. Read Lead With Respect. You can also buy the entire Gold Mine trilogy of all three Shingo-winning books, plus a 135-page study guide, for $75, a savings of $40.