Of all the articles in this five-part series, this final article, on the subject of measurement, has taken the longest to write. I’ve gone through many iterations.

Why? Measurement is always a challenging subject, and it requires us to dig deeply into the question of value. What do we measure? Why? What do those measurements really mean? What is their purpose? How do they help us improve? How do they help us drive innovation, so we can stay ahead of the competitive game?

Add to these challenging questions the fact that technology is exponentially increasing the amount and nature of information available to us. This leaves us to wonder, how do we access the right information to help guide us to customer value, not only within the enterprise and its processes, but across the global marketplace?

In the past year I’ve visited five continents, observing and engaging with countless enterprises who are addressing this challenge. The goal of these visits is to help enterprises effectively and efficiently leverage technology’s capabilities to better understand, create, and deliver customer value. Their path to accomplish this goal involves integrating lean IT capabilities fully within their culture, strategy, management systems, and value streams. I come to each of these interactions in a variety of roles –as coach, leader, teacher, researcher, and always, as a learner.

My goal with this final article in the series is to share this learning with you, offering a foundational structure to help you and your teams identify an approach to measurement throughout your enterprise that will guide us towards customer value. I also offer a high-level overview of the role of technology in measurement, both within the enterprise and in the marketplace, showing how carefully selected and applied existing and emerging technologies are greatly expanding our ability to identify and improve customer value and drive meaningful innovation.

Technology’s growing capability plays out in all aspects of value streams, but it is from a perspective of measurement that IT helps us to better understand, develop, and deliver what customers want. A technology-savvy Lean enterprise can make significant gains and achieve real competitive advantage, not only by improving products and services, but also by improving the ability of everyone within the enterprise to listen and learn.

Changing Our Thinking about Measurement

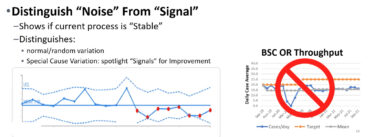

We live in a world where there is no shortage of data, with plenty of fascinating devices that feed us information constantly. But more measurements, and more data, is not necessarily better; we are quickly becoming a generation of information junkies and this overload does not necessarily add value and may obfuscate it. So we must be clear about what is important, else we become overwhelmed by noise.

One of the most common measurements that misleads us in our quest for value is cost. In many enterprises, an inordinate amount of effort is expended to determine what something costs, and to focus on directly cutting those costs — reducing staff, spending, projects, services, education, development, and continuous improvement efforts—in order to improve the bottom line. But without understanding the drivers of value, such indiscriminate cutting can reduce value and harm our relationship with our customers, and ultimately, threaten the very health of the enterprise.

Lean enterprises move beyond this thinking, shifting to reducing waste rather than cutting costs. As a result their costs are usually lower, their quality improves, their capacity increases, and their relationship with their customer improves, leading to growth and innovation opportunities. In my workshops I often lead people on an exercise to distinguish between cost reduction and waste elimination in their own environment. Can you tell the difference? Start with the age-old Hippocratic Oath: First, do no harm.

Another common mistake is to create performance measurements and incentives that aren’t tied to the creation of value. As an example, consider the traditional month-end, quarter-end, year-end sales incentives where salespeople double down to hit their targets and earn their bonuses. This sends customer service and production teams into overdrive, often resulting in mistakes due to hasty hand-offs from sales, and production spikes where quality and cost suffers. Ultimately, a measurement comprised solely of sales volume (or other one dimensional outcomes) can lead to poor quality and customer satisfaction and reduced profits.

The lean approach takes a value-stream view, working with customers, leveling out demand, delivering less more frequently. This requires a new way of looking at efficiency – switching from a mindset of mass production based on high volume and low cost, to an economy of flow, giving the customer just what they want, when they want it.

Here is where IT capabilities can add substantial value to a traditional enterprise that is on the lean journey. Emerging technologies enable us to communicate, and indeed, collaborate with customers on a large scale, easily and efficiently within these value streams. Here too, there is a plethora of data which can easily become waste. The key is gaining an understanding of what these technologies offer and making informed decisions about which to experiment with and integrate directly into your value streams, always with an eye to mining and measuring the right information.

So within this framework of integrated value streams (where technologists and business colleagues work collaboratively) we’ll explore how to take a targeted approach to identifying and measuring what creates value.

The Five W’s

Here is the approach that I propose in order to establish measures that lead us to customer value. Though effective measurement can be a complex issue, by following the tradition of lean we look for simplicity underlying the complexity. In a lean culture, to identify root causes people learn to ask the question “Why” five times. I propose similar simplicity. To create effective measurement approaches, I propose we ask the well known “Five W’s” – Who, Why, What, Where, When. Who represents people – the customers as well as the people who do the work; why represents purpose; what, where and when represent process.

We’ll look at measurements obtained within the enterprise related to internal processes. We’ll also look at measurements obtained in the marketplace, where technology is dramatically changing how we can interact with and learn from our customers.

Who

As always, we begin with the fundamental question of lean: Who are our customers? We should start with the end customer, but as we consider the issue of measurement, we need to look at the entire chain of intermediate customers that play a role in the value stream. This examination may enable us to identify key process drivers (e.g. stakeholders, enablers, constraints, failure modes) where measurement and monitoring can improve the overall value stream.

For some teams, especially those at the front-lines, the end customer is their direct customer. But for many internal teams (such as in IT operations) their direct customer is the downstream recipient of their work. Some teams provide shared services, such as network and communications, or human resources, or facilities management, serving countless internal and end customers. In these cases, often obscure costing and chargeback calculations that attempt to spread the cost of these shared services across the organization further complicate the question of cost and value.

As lean accounting practitioners will tell you, such separation of cost from the value stream rarely leads to informed consumption and investment decisions. So the first order of any measurement system is to understand “who is the end customer” and if the team serves an intermediary customer, the team must develop and understanding of who their internal customers are, and who their customers’ customers are all the way through the entire value stream to the end customer. They must understand how their actions affect them, how value is created. This is what lean practitioners refer to as “line of sight to value.”

Once we’ve identified our customers (and potential customers) the next question to ask is what do we know about them? What should we know? What do we think we know, and how do we validate it? This is where we turn to the marketplace to gain a more nuanced understanding, and this where technology can play a vital role. At the 2012 LEI Lean Transformation Summit I presented a learning session on business intelligence for the lean enterprise: how IT is enabling progressive enterprises to more actively—and effectively—engage with the “virtual voice of the customer.”

Aided by technology, we’re now able to learn not only what customers think of our products and services, but also what they think of our competition, what they’re searching for, what they like, how they use it, and what they might like in the future. We can identify which of our customers are most likely to tell their friends about us—and we can listen to what they say. This is just the tip of the virtual information iceberg of big data analysis and social media listening technologies.

Technology also enables us to talk with our customers in ways we never have before. Through interactive media, something as simple as chat, customers—and potential customers—can learn more about our products and services. They can self-serve, creating the perfect Lean pull for exactly what they want, when they want it. (For an example of lean thinking across a vast supply chain with sophisticated, complex, configurable products and services, visit www.dell.com). We can also invite customers to collaborate with us on a large scale to innovate and improve what we do. (Proctor & Gamble’s open innovation target is to have over half of new product ideas come from outside the company.)

Working together, business and technology colleagues can make informed investment decisions about social media listening, point of sale and big data analysis, mobility, and other emerging technologies. Together they can decide what to listen for, and whom to communicate and collaborate with. All this information, all the measurements mined from a variety of sources, can greatly inform our investment, improvement, and innovation strategies. With the pace of change accelerating, we have to be more innovative about how we innovate. We can’t rely on luck and a handful of “creative people” . . . not anymore.

Can these new technologies be costly and filled with risk and uncertainty? Yes, but they don’t have to be. The key is to develop a hypothesis about a product, a service, a customer . . . and then find the simplest, fastest, cheapest way to test it. Over and over. PDCA accelerated. This is the message of The Lean Startup; you don’t have to be a high-tech startup to think and act like one.

The question of “who” in relation to measurement also relates to who does the work. We’ll address this later, as we near the end of this article.

Why

Consider this statement attributed to Henry Ford. “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said ‘faster horses.'” Understanding why our customers want something—the purpose—can often lead us to true leaps in innovation and value.

Our measurements should reflect that purpose. But when the work is done far from the end customer, or as a shared service for many internal customers, the connection between the work we do and the purpose it serves for the end customer can be obscure.

As we consider the role of technology in measurement, let’s consider for a moment how to effectively measure IT performance itself. Historically, IT has operated as a functional silo (in fact a collection of silos) far removed from the end customer. Consequently, technologists often don’t have clear visibility to the customer, or what the end customer really values. For this reason, meaningful measurement of IT services has been elusive. Within IT, we can produce volumes of measurements, but which of these measurements reflect purpose? Often we’ll measure what IT does in terms of system performance or service level agreements, but those measurements may not correspond to what the customer needs and wants in useful ways to guide our behavior, decisions, and investments.

To help us find the right purpose driven measures for IT services, it’s important to ask another seemingly simple question: what is IT and what is its purpose? This is a simple question, but it has a multi-faceted answer. I propose that IT is defined by the core capabilities that it delivers:

1. Quality information and effective information systems that enable business processes to serve customers

2. Information gathering and analysis to manage process performance and to develop a clearer vision of customer needs and wants

3. Technology-enabled features and functionality that add value to the products and services the enterprise delivers to its customers

4. A medium for information exchange, communication, and collaboration among the enterprise, its customers, and the larger marketplace[1]

When you first mention enterprise IT, the first and second categories of capabilities usually come to mind. But it’s the third and fourth – with the rise of popularity of mobile computing, big data analysis, and collaborative and social tools – that have inspired investment in game changing innovation in many industries. For example, think of the transformational value that (properly implemented) Electronic Medical Records offer in healthcare, and how internet and mobile capabilities are revolutionizing financial services. Suddenly IT is now in the boardroom of many enterprises, informing and often driving strategy. And it’s happening fast – in some cases very fast.

While each of these four categories is considered “IT”, the purpose of each is subtly different, and it is important for each team to understand how their activities contribute to end-customer value in each case. So as we strive to effectively measure IT performance, the data collected—what we measure—should directly reflect (either in its original state or when combined with downstream activity in the value stream) the achievement of one of these four purposes.

Now let’s shift our attention back to measurements of purpose within the marketplace, to how the same technologies we use to identify and learn about our customers can also help us to better understand what these customer value. What are people saying about our products and services? About the features? What are they saying about our competition? If ever you wanted an example of the value and the power of social media in the marketplace, visit Amazon.com and read a few reviews. Here you’ll learn not only how well the product solved the problem—not just the primary problem, but also the smaller, value-adding details that are critical but easy to miss if you’re not paying attention.

Recently I shopped for an inflatable neck pillow for those long airplane rides. When you visit Amazon.com you can find well over a thousand reviews written by people who really care about neck pillows. None of these reviewers talk about how well they were able to sleep on the airplane. What they do talk about are the features that help achieve the purpose—how easy is it to inflate and deflate; how soft is the material against their skin; is it easy to wash; how durable is it; how good is the support?

Does it surprise you that ordinary people like you and I invest so much effort in writing about seemingly mundane products? People are generous when they connect with a sense of purpose, something that is meaningful to them and potentially helpful to others. Why have so many people have given their time to create Wikipedia? Because they care.

Do you know how to tap into your customers and their sense of purpose in this way? What reasons do they have to care about the products and services you offer them? How can you help them find their voice? Think about it, formulate a hypothesis, and test it quickly and cheaply. Don’t just talk with your customers – connect with their purpose.

What

With a clear understanding of who we do the work for, and the purpose of the work, now let’s consider the actual work—what we do. In establishing measurements, teams need to ask how what they do contributes to value for the customer. Is the work increasing reliability, functionality, speed? What is the problem we’re trying to solve, after all? What is it we are doing that solves the problem?

In a manufacturing environment, identifying what to measure may be fairly clear. Building a car—or a neck pillow—is tangible; the work is visible; we can see the flow from beginning through the intermediate steps, to the end customer. But in environments where the work is not visible, such as IT or financial services, identifying what to measure can be more challenging.

IT workflow is often virtual and invisible. As a result, it has become increasingly popular to “instrument and monitor” an excessive scope of events and transactions, creating vast new oceans of data that are supposed to help us improve processes and become more cost effective. But it often doesn’t work that way; just as any other form of excess inventory and over-processing, excessive data capture and exception notifications can be waste (muda). We must be careful what we instrument and monitor, and why. We need to understand flow of value, so we can monitor and address those things that impede it.

In any environment, but especially non-visual environments, the technique of value-stream mapping can be useful as it helps the team to understand and quantify the flow of value so they can identify and prioritize the obstacles in their way. This is one reason why the kanban technique has also become so popular in the world of IT – both in development and operations. Using just a whiteboard and sticky notes, teams can often illuminate and unravel non-transparent and overly complex processes, reducing them to a simple visualization of flow from demand, to backlog, through wait states and blockages, to completion. When demand, velocity, and congestion are visualized then problems become visible, calling attention to themselves without complex monitoring systems.

Visual measurement and management helps teams solve problems and create flow, and often the best measurement system doesn’t need a computer.

Where

Where is the work done? Where does the customer receive value? These locations are known as gemba. Lean practitioners know that work should be done as close to the customer as possible. Why then, is this not practiced when we consider proximity to internal customers?

This is a frequent issue in IT, where often technologists’ offices are located some distance from main campuses, or in another section of the building, or on another continent. I’m beginning to see more and more co-location, creating true cross-functional teams and integrated value streams working together in a shared space. Yes, geographically dispersed teams can use a variety of communication and collaboration tools, but don’t underestimate the value of direct relationships —a quick conversation in the hallway, a short stand-up meeting or problem-solving session in front of a visual display or obeya room. Measuring proximity, latency, and frequency of communication and problem solving among the team and with the customers (direct and indirect) can lead to some valuable insights, and improve speed, quality and cost of project delivery.

Given that, we have to ask, why have many enterprises distributed their IT organizations? Sending development work to far flung locations with low labor costs? Sending data centers and system administration to large outsourcers that promise reliability and low cost? It’s roughly the same calculus that led U.S. manufacturers to outsource their production to low cost countries years ago. What did they learn? That there is much more to consider than just unit labor cost. That is why many are now trying to “re-shore” their production, only to learn that much essential knowledge and skill has been lost. Some large IT organizations (including the “new” General Motors) are reversing this trend, re-shoring their staff, and rebuilding their internal capabilities.

I’m not advocating against outsourcing, offshoring, or strategic partnering in general. In fact, many highly innovative companies are using an open innovation model where partnering across enterprises can introduce powerful multi-disciplinary talent and ideas. I am suggesting that when we partner, it should be on the basis of value and capability development, not simply unit cost reduction. We need to measure total cost of ownership, speed and agility, and product/service lifecycle innovation. We must remember the value of purpose, process and people. In the end, team relationships are both intangible and highly valuable for knowledge work. Once we have streamlined, standardized, and to the degree practical, automated our repetitive processes, we realize it is our knowledge, our shared purpose, and the relationships among ourselves, our partners, and our customers that are key to innovation and sustaining market advantage.

Where the customer receives the value is another often underutilized source of useful measurement. When we engage directly with our customers we can gain a better understanding of purpose, about what our customers really value. This is another area where emerging technology can dramatically improve what information we’re able to obtain and analyze. For example, most automobiles now have on-board computers, and many link directly to satellites or can be downloaded when the vehicle is serviced. Herein lies a wealth of data for measurement about how customers are using the product (and product components) and this information can be shared within the value streams, including supply chain partners, to guide improvement and innovation efforts.

So you’re not a big company with a large budget for this sort of thing? How can you connect with your customers without spending a bundle? Consider this – growth in mobile phone applications surpassed computer-based internet usage over a year ago, and mobility continues on a stratospheric growth path. Many people are now continuously using mobile devices to interact with the world around them, to make decisions about how they buy and use products and services. What can you offer the marketplace to get customers to interact with you? What can you learn from their use of your applications? Here to, this medium can become the “C” of the rapid PDCA cycle as we test in small batches in controlled circumstances in the marketplace.

Keep in mind, this is not about silly gadgetry; this is about connecting with customers and finding new ways to create value for them. And if they have fun, or find a human connection along the way, that’s nice too.

When

When does the customer (both end and internal) want the product or service? How often are we on-time? These are straightforward measures that every Lean enterprise, even non-lean enterprises, employ. The more challenging, and more valuable questions are: When do we measure the process performance? When do we measure the improvement to that process? When do we measure ourselves? The answer is simple: as often as is needed.

A product development team may have a daily standup meeting where they synchronize their efforts and track their progress. In a financial services organization, thousands of transactions may occur every minute, or even every second. While deep in the computing environment of servers, networks and storage, monitoring and feedback cycles may be measured in milliseconds. No matter what the type of work, similar to a Just In Time factory environment, the smaller the batch size and cycle time of every form of work creates more frequent “learning loops” (PDCA feedback cycles) where the process can keep itself within bounds, and tell the value stream team when problems are emerging – but before they arise and cause defects.

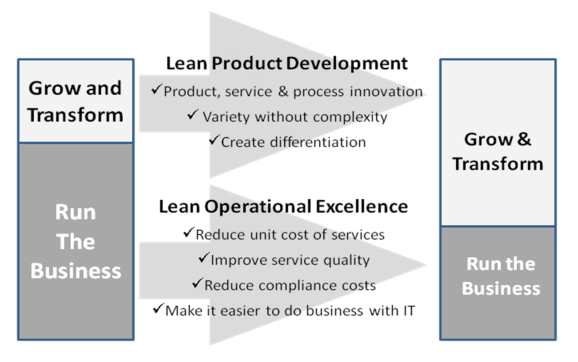

This process-specific cycle time should inform the feedback interval. As any work environment is gradually understood, stabilized, visualized and standardized, the team evolves from reaction and corrective action, to prevention, and ultimately prediction. When a team spends less time reacting to problems and more time anticipating customer needs and wants, this causes a shift in attention (and investment) from operations to innovation, shown in the following figure.

[1] Run Grow Transform: Integrating Business and Lean IT, Appendix A – What Is Lean IT? A Working Definition (Steve Bell, © 2012 Productivity Press)

Image from Run Grow Transform (© Steve Bell, 2012, Productivity Press)

Now let’s go back to a question raised in the beginning of the article: Who does the work? No matter what we do to the process, no matter what technologies we employ, the most valuable resource within our enterprise is our people. One of the most valuable but least used measurements is of how our employees feel about the enterprise, its leadership, and their work. In the long run, the most important factor in the long-term success of an enterprise is whether the people are engaged and able to fully contribute and adapt to changing conditions.

Do they feel a sense of purpose, of pride in what they do and way they do it? Are they able to learn and apply that learning to adapt, to improve, to run, grow, and ultimately, transform? That is the one true key to sustainable competitive advantage, and it cannot be copied by a competitor; it must be developed from within. This is why – though we may endlessly study, reflect, and aspire to be like Toyota, like Southwest Airlines, like Amazon or Google – it makes no sense to imitate them. We must learn to learn like them. That’s purpose, process and people.

Who is the customer and what is the problem we are trying to solve?

As I bring this final installment in this article series to a close, I am reflecting on the strategic importance that IT plays in every enterprise to help people learn and succeed. I am also reflecting on the fact that, since the dawn of business computing in the 1950’s, we have been wrestling with the need to “align and integrate” business and IT. This challenge is suddenly more important and urgent than ever before.

If you have been following this series, or have read Run Grow Transform (just published last month) it should be evident that there is no one thing called “IT”. IT is a set of capabilities around which technical communities, even sub-communities have formed. Over time, these communities have developed their own identities, their own methodologies, their own measurements of success. And often they compete for the same budget. Yet for all their differences, their functions do not exist in isolation, from the business or from each other. They are interdependent, and optimal Lean functioning requires an integrated, holistic view, with everyone working together along value streams, unified in the goal to serve the end customer.

It is the principles of Lean—the purpose, process, and people that enable true collaboration among all value stream stakeholders (including technologists) with a unified focus on True North to improve value to the customer so the enterprise can run, grow, and transform. After all, competitive advantage is a product of how quickly we are able to learn and adapt.

To learn more:

I’ll be talking about these and other concepts at upcoming Lean Enterprise Institute and Lean Global Network events, including:

- Lean IT Workshop – The Lean IT journey depends on continuously improving people, process, and technology, in that order.

Links to previous articles in this series

- Lean Business-IT Integration, Part One: Who Wants to Go Talk to IT About This One?

- Lean Business-IT Integration, Part Two: Obstacles to Value-Stream Transformation

- Lean business-IT integration, Part Three: What is an integrated business-it Value Stream?

- Lean Business-IT Integration, Part Four: The Lean Learning Leader

Steve Bell is a member of the Lean Enterprise Institute faculty, the author of Lean Enterprise Systems: Using IT for Continuous Improvement (Wiley, 2006), co-author of Lean IT: Enabling and Sustaining Your Lean Transformation (Productivity Press, 2010), recipient of the 2011 Shingo Prize for Research and Professional Publication, and author of Run Grow Transform: Integrating Business and Lean IT (Productivity Press, 2012). He is the founder of Lean IT Strategies, a lean leadership education and coaching firm, and Lean4NGO, a non-profit community dedicated to bringing Lean practice to humanitarian organizations.