Lean hospitals tend to focus on service as the conveyor of customer value: What’s the wait time? How many return visits are required? Is this duplicate information really needed? How long did the procedure take?

But a construction project underway in Akron, Ohio, for Akron Children’s Hospital (ACH) demonstrates that a hospital’s facilities are just as important to delivering the most value at the highest efficiency and lowest-possible cost.

When the Ambulatory Surgery & Critical Care Tower opens in 2015, it will represent a three-year lean design and construction collaboration among builders, architects, trade contractors, healthcare providers, patients, and patient families. The design of both the facility and future operations is being shaped directly by patients and those who care for them. Input from nurses, doctors, therapists, technicians and patient parents heavily influenced design decisions—from incorporating emergency room hallways that protect the privacy of abused children to the number of electrical outlets in each neonatal intensive care room.

The hospital needs the new space to serve a growing patient population, but it’s also viewing the project as a way to “bake in” lean practices and flexibility to adjust to emerging care models and changing patient needs. The project will cost much less than a traditional construction project, too. So far, front-end design teams have trimmed about $20 million in cost by reducing baseline square footage estimates, and the hospital expects another 20 percent cost reduction during the construction phase. ACH has a deeply embedded lean-based operational excellence culture, but this is the first time it is applying lean principles to a new-construction project.

“We’ve never had these kinds of discussions about a construction project at the hospital before,” says Doug Dulin, director of the hospital’s Mark A. Watson Center for Operational Excellence. “We’re asking, “Do we understand our future state? How will we design this building to be flexible and adaptable for the next 20 years? How do we optimize patient movement?

“We’re really interested in the long-term. This project is going to shape the care that Akron Children’s Hospital delivers for the next 20 years.”

| Akron Children’s Hospital at a Glance • Largest pediatric healthcare system in northeast Ohio. • Operating two freestanding pediatric hospitals and offering services at nearly 80 locations. • Pediatric specialties draw half a million patients annually, including children, teens, and adults  Ambulatory Surgery & Critical Care Tower • Estimated to cost $200 million • Six to eight floors A new emergency department with enough capacity to meet current and future demand. Annual visits of more than 60,000 strain the hospital’s resources in a facility built to accommodate 44,000. The emergency department will have three larger trauma bays to quickly care for the most serious medical problems, and about 33 treatment rooms, an increase from 29. A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) located on two floors with about 72 private rooms accommodating 75 infants with three “twin room. This is an increase from 59 neonatal beds (none of them private rooms). The hospital has had to get special permission from the state multiple times during overflow situations in its nationally ranked NICU. Ambulatory surgery center with between six to eight operating rooms designed in response to a more than doubling of outpatient procedures in the past 20 years. In addition, the plan calls for: Assisting in the expansion of a nearby Ronald McDonald House of Akron to accommodate the hospital’s growth; new six-level, 1,200 space parking deck, already under construction; and a new “front door” for the hospital—a child- focused patient and visitor welcome center that will streamline access to the campus. The companies assisting with project management include: The Boldt Company, Appleton, Wis.; Hasenstab Architects, Inc., Akron, Ohio; KLMK Group, Richmond, Va.; HKS Inc., Dallas, Texas; and the Welty Building Company, Akron, Ohio. |

Integrated Lean Project Delivery

ACH chose the Boldt Co. of Appleton, WI., as general contractor because the company offers an option called Integrated Lean Project Delivery System (ILPD)® that is based on lean-design principles (read an interview about ILPD®). The hospital expects the ILPD® system to improve productivity, eliminate waste, enhance the overall patient experience, and reduce costly change orders in the construction phase as well as the project’s overall cost. It should also continue to reduce expenses over the long term because by design, the project team is planning for integration of future medical technology as well as social and demographic changes that will alter demand.

“We are building flexibility into our design so that we can be prepared for the changing healthcare environment,” says Grace Wakulchik, COO of the hospital. “For example, we are designing our new neonatal intensive care units so they can become pediatric intensive care units or even general patient rooms if our patient volumes and patterns change.”

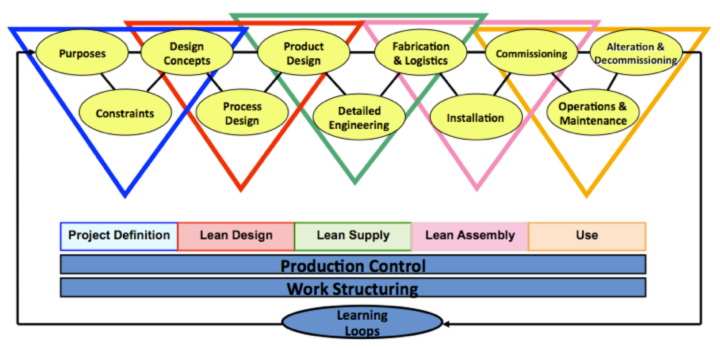

The project started with an implementation process known as Target Value Design (TVD), which proceeds through the five phases of ILPD: project definition, lean design, lean supply, lean assembly, and use. As the project moves through the phases, pressure on cost drives innovative solutions in design, fabrication, and installation, according to Boldt.

Project cost is first defined as “allowable cost,” which is the top figure that the client is willing to pay. The team then develops the “expected cost,” which is a detailed, market-based estimate derived during a validation study of the project. Finally, as design begins, the delivery team and client establish a “target cost” below the expected cost, and everyone works collaboratively toward that target. The target cost is based upon development of stretch goals with an eye toward driving innovation and eliminating waste.

Target Value Design

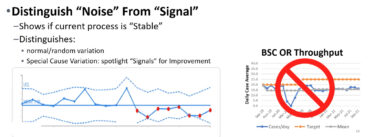

Target Value Design (TVD) is a disciplined management practice that is used throughout project definition, design, detailing, construction, commissioning and activation to assure that the facility meets the operational needs and values of the users, is delivered within the allowable budget, and promotes innovation throughout the process to increase value and eliminate waste (time, money, human effort). TVD is emerging as the “science” of Lean Design, replacing the traditional design process and sequence.

Source: The Boldt Company

Much like lean product design, the process begins with a discussion on feasibility within known constraints, and then moves into an intensive set-based experimentation phase in which a cross-functional team starts with a conceptual design and then experiments to refine the design for maximum value and minimal cost. ACH created a team for each department that will be occupying the tower: emergency medicine, neonatal intensive care, and ambulatory surgery. The teams met multiple times to map their current states, plan their future states, form a conceptual design, and then redesign, test, and redesign more to reach target-cost goals.

Design, Test, Redesign, Test, Redesign

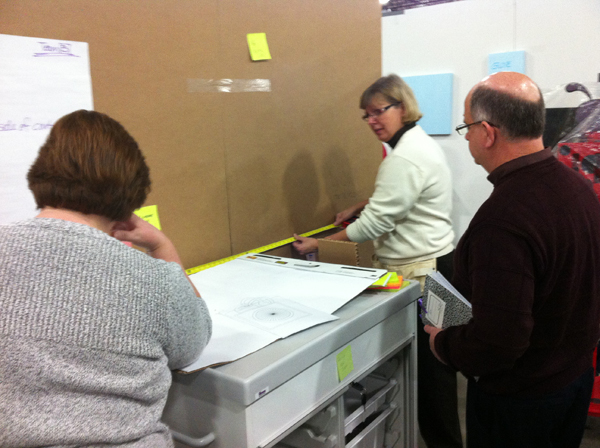

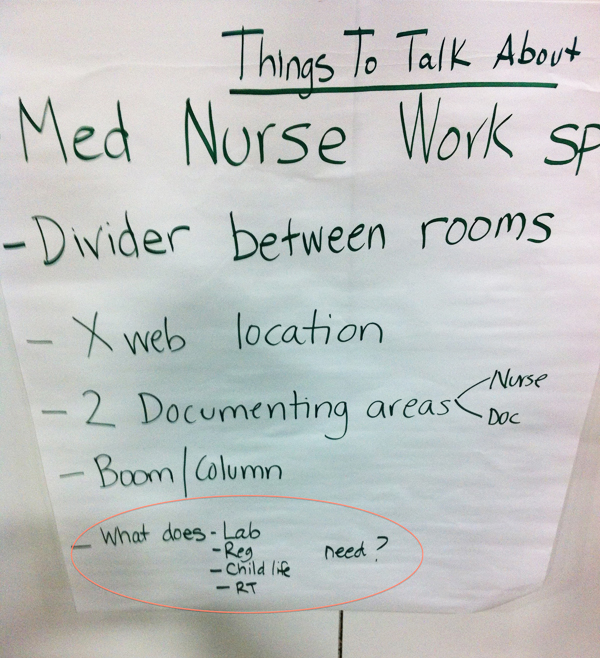

The testing took place at a warehouse outside of Akron and used 2P and 3P fundamentals. Moveable cardboard walls were used to simulate actual walls, and real furniture, equipment and supplies were brought in. Even photos of oxygen ports and electrical outlets were posted on the cardboard walls and up for discussion.

Throughout the testing of these full-scale prototypes, the teams focused on testing the facility for how it would support lean operations. The teams ran multiple scenarios scripted events representing real-life cases—to test the designs layout and configuration. With doctors, nurses, parents and other practitioners assuming “roles,” they ran through a complete visit from check-in to checkout, including hands-on procedures. During the scenarios testing, the team would collect data to evaluate operational efficiency. They would then reflect and discuss challenges such as where to store equipment, how to keep patients and their families comfortable and calm, how to store supplies for efficient use and restocking, how to communicate with one another, and how to plan-in “buffer” space for patient overflows and other unexpected needs.

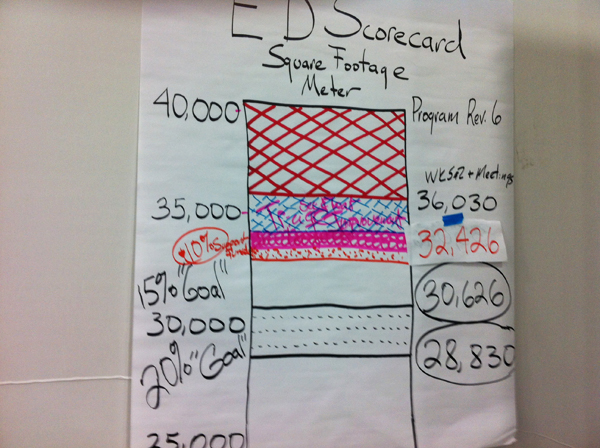

As of the end of 2012, when the teams were going through final testing of their designs, they had reduced baseline square footage by 10% to 20% on each floor, saving the hospital an estimated $20 million in direct cost.

In addition to the cost savings, teams worked to take out other waste and build in level loading of processes. For example, the emergency medicine team set aside 10,000 square feet for a possible “urgent care” area, where non-critical patients could be treated by a doctor and/or nurse practitioner instead of an emergency-medicine specialist.

“That’s 15% to 20% of those patients that could be seen in the urgent care area without hitting downstream processes,” Dulin says. “These are patients being treated for things like sinus infections, so they really don’t need to be seen any further downstream. It’s really going to improve our efficiencies.”

The ambulatory surgery team trimmed 30 minutes out of average wait time as they worked on department design. And in the NICU, the hospital purposely designed private rooms because there’s recent evidence that when a critically ill newborn can stay in a room with its mother and be nursed, both go home three to four days earlier, Dulin says.

The teams took that concept even further during the design phase, and now ACH is in negotiations with a nearby full-service hospital to run birthing suites in the tower so that mothers who know they will be delivering a baby that will need immediate critical care can deliver and recover from delivery while staying as close as possible to their babies.

Learning and Involvement

In addition to the medical professionals, the cross-functional teams included members of support services, such as information technology, procurement, maintenance, and social services; and functional teams also formed as responsible parties for achieving major construction milestones. For example, a Site Team handled permitting and making decisions on questions about site issues, such as storm water management. All of these activities were coordinated through a Master Pull Plan.

Unlike typical design-phase scheduling, the responsibility-based Master Pull Plan focuses the teams on determining the “last responsible moment” for closing an action, which promotes just-in-time decision-making. In traditional schedules, these decision points can become bottlenecks that cause accumulation of waste in the form of waiting. Also, the heightened visibility provided by the pull plan allows the larger team to identify and prepare for those decisions that require integration of work from multiple cross-functional teams. This guards against the rework and overproduction that typically happens without this visibility.

“Our partner teams have constantly looked at taking out cost from construction, such as decisions like whether to build something on site or buy it prefab,” Dulin said. “They’re projecting that we are going to see a 20 percent reduction on the construction side from lean principles.”

Internally, the tower project has increased learning throughout the hospital. Doctors, nurses, technicians, business process managers and executives had already been participating in lean education and benchmarking. Through this process, they’ve learned elements of lean design and have expanded their lean thinking.

“When I initially got involved with this, I thought ‘designing a building,’ and a building is just concrete walls and rooms,” said emergency department doctor Maria Remundo. “What we’ve learned from this is that we’re creating a whole new way of delivering emergency medicine. We can’t build a new emergency room every 10 years, so we had to look at how we are going to meet our current needs as well as our future needs.”

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.