How well does your budget serve its purpose? Asking this question can lead to a rich and revealing discussion with operational and finance teams alike. In order to gauge the effectiveness of the budget (both the process and the set of outputs or tools), we likely need to start by agreeing what effectiveness is measured relative to. What is the purpose of the budget? Why do we engage in the budget process and produce the outputs it generates? How do we use the budget during the year to check-adjust performance? Who are the end-users of the budget and what are their requirements? How does the budget help us improve customer value – and do our customers care if we have a budget?

I do not intend to be exhaustive in this article; there is an entire body of knowledge around Lean Financial Planning – and the closely related body of knowledge on “Beyond Budgeting.” My hope is to inspire curiosity and provide concrete next steps to explore the opening question – “how well does your budget serve its purpose?” – in your organization.

Let’s start with the purpose. One key purpose of the budget is to provide a target that we can check against and hold ourselves accountable to: are we on track to achieving the financial results we require? Another common use of the budget is to provide a forecast: based on current and planned activities what do we think our financial performance will look like (so we can see if there’s a gap to our requirements, understand the gap and plan adjustments)? Yet another key purpose may be to allocate resources: will we have the right people, materials and tools in the right place at the right time to deliver on customer requirements?

Now let’s talk about how well the budget serves those purposes. In the organization where I played a finance leadership role, the budget was intended to play all of these roles. In developing the budget we forecast revenue and expense, then made adjustments to each of those, incorporating assumptions and initiatives that created an operating plan in support of our financial goals – allocating resources in alignment with the plan, and ultimately used it as a way to track results.

Once the operating year began, however, the tools and process no longer effectively served any of these purposes. We no longer had a true forecast because we adjusted it with assumptions; actual business results varied to a small or large extent from the plan and instead of using them to learn and improve – asking “why the change in performance” – we focused instead on explaining the variance. Most of all, the static budget and control tools and processes associated with it did not support our lean strategy and continuous improvement activities – learning from experiments and then needing to adjust plans, resources and/or timing. The budget process focused us more on what we could impact near-term rather than strategic, value-stream, or continuous daily improvement which benefitted from regular reflection – check/adjust – what did we try, what did we learn, what are the obstacles impeding improved or optimal financial performance (and the root causes) and what will we try next. So we were trying to practice continuous improvement while locked into a financial planning box. In addition to not ideally meeting the purpose, it was very resource intensive, consuming hundreds of hours of operations and finance staff time each year.

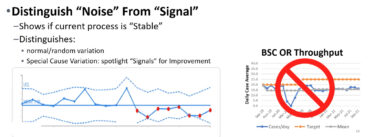

Three years into our organization’s lean journey we chose to step away from the budget and develop alternative processes and tools that could better serve us. We developed a rolling forecast process (typically quarterly) that always looked at least 6 quarters into the future and because it was separate from the target its purpose was to provide an unbiased perspective of future performance that we could then use to problem solve (target-actual-gap-root cause) and inform improvement plans. We worked with operations to understand what key processes drove financial outcomes and used those insights to set up monthly, weekly and daily indicators that operations used to manage and improve the processes that contributed to financial outcomes (as well as quality and delivery). We delved deeply into the Beyond Budgeting literature and got coaching from our lean senseis. Finally, leadership had already adopted lean strategic planning and deployment and we shifted resource allocation (both operating and capital) to our quarterly deployment check-adjust process, allowing the organization to plan and adjust resources intentionally in alignment with strategy.

Now that we had planned and implemented a solution to a problem, the next question became “how will we check?” – so that we would know if we had made improvements. There were a few main ways that we checked. We implemented standard work to regularly assess with end users the utility of the financial driver and key indicator reports that replaced the budget variance reports. A required question in the evaluation was “How does this tool inform your ability to make improvements in customer value?” We also implemented standard work to regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of report production; identifying and eliminating waste to improve first time quality and free up capacity for the finance staff to focus on other important work. For our forecast process, we implemented standard reliability assessment tools to check for bias and inform improvements in our forecast methodology.

The new processes and tools better met our needs and were significantly less burdensome on resources. Just like any process improvement, there was a good deal of experimentation and check-adjust required; some aspects of the new processes worked reasonably well soon after being implemented, others required years of reflection and adjustment. The point of sharing the example is to illustrate the potential value of considering what you most need to accomplish with your financial planning processes and tools (budgets, variance reports, key indicator reports, dashboards, etc) and therefore what is the most effective (meeting end user requirements) and efficient (continually driving out waste) process possible.

Let’s come back to another question I asked at the outset – do our customers care if we have a budget? Our customers care about their ability to get our product or service in way that meets their quality and delivery requirements at a cost that is commensurate with those. So our financial planning tools and processes are non-value added, but necessary for the business to effectively plan, do, check and adjust financial performance. As non-value added but necessary work, we continually strive to make financial planning processes as effective as possible while minimizing the burden on the organization. Many budget processes are neither effective relative to their purpose(s) nor are they minimally burdensome.

I encourage you to take a thoughtful, critical look at your financial planning processes. What purposes do they need to serve and for whom? How can they serve those purposes most effectively and with minimal waste so that operations and finance teams can focus their skills and capabilities on work that has the biggest impact on improving customer value? These questions can lead to productive discussions that result in PDCA of processes and tools that far better meet your financial planning and control needs over time.