Editor’s note: In the 25 years since Lean made a splash beyond Japan, and in recent years especially, we’ve seen a pull for lean government here in the United States (from both sides of the aisle) and across the globe. From the State of Washington to municipal process improvements in Michigan, Saskatchewan, and the City of Melbourne, to the EPA, public sector agencies are making things better for the public through the application of lean thinking and practice. In addition, communities of practice are self-organizing and beginning to make a meaningful difference. Building on the lessons learned from the ThedaCenter for Healthcare Value’s Healthcare Value Network, the Lean Enterprise Institute will soon be launching the Public Service Value Network in partnership with lean pioneers in the public sector. LEI hopes to improve awareness of how lean thinking and practice can improve the effectiveness, quality, and delivery of public services and accelerate the adoption process. To keep the lean government conversation going, we are sharing Jim Womack’s essay “Lean Government” here, originally published in Gemba Walks (Expanded 2nd Edition).

Editor’s note: In the 25 years since Lean made a splash beyond Japan, and in recent years especially, we’ve seen a pull for lean government here in the United States (from both sides of the aisle) and across the globe. From the State of Washington to municipal process improvements in Michigan, Saskatchewan, and the City of Melbourne, to the EPA, public sector agencies are making things better for the public through the application of lean thinking and practice. In addition, communities of practice are self-organizing and beginning to make a meaningful difference. Building on the lessons learned from the ThedaCenter for Healthcare Value’s Healthcare Value Network, the Lean Enterprise Institute will soon be launching the Public Service Value Network in partnership with lean pioneers in the public sector. LEI hopes to improve awareness of how lean thinking and practice can improve the effectiveness, quality, and delivery of public services and accelerate the adoption process. To keep the lean government conversation going, we are sharing Jim Womack’s essay “Lean Government” here, originally published in Gemba Walks (Expanded 2nd Edition).

About 10 years ago I got a call from the mayor of a major American city who told me he wanted to create the first “lean” city government. What this might mean was unclear to me. I knew nothing about his city and had done no thinking about lean in government at any level. So I went to see him and we had some fun looking at a couple of sample processes: arresting vagrants and processing building permits.

We put a brief effort into taking gemba walks along both value streams, discovering that the best thing to do with vagrants was to create a separate process (a vagrant product family if you will) that was quick, simple, and removed from the arrest process for actual criminals. (This meant the vagrants could be treated more humanely and officers could get back on the streets much more quickly. The important question of whether vagrants should be arrested at all was left for another time.)

By contrast, issuing building permits in this growth-oriented city was straightforward. Rather than asking contractors to come to city hall in the middle of a vast metropolitan area far removed from where buildings were actually being built, it made more sense to create four processing centers in the four quadrants of the city. And instead of sending the permit requests through four different departments, with queues and delays in each department, the countermeasure was to colocate the parts of each department concerned with permits, and pass the applications around a table, pretty much in single-piece flow. It seemed possible to reduce the wait time for a building permit from a month to a day.

So far, so good. But then bureaucracy and politics came into play. The mayor had a limited attention span—I’m being generous—and no one was given responsibility for overseeing the new processes and perfecting the flow of value across different departments. Then, it turned out that resources were needed to do rigorous experiments to test the ideas, and the project had to be put out to public bids—a process that was a nightmare. Ultimately, nothing much could be done or sustained by the earnest line managers without continuing upper-level support and I gave up the effort. It was another interesting gemba walk for me, leading to some great insights on how poorly the existing processes were designed and what might be done to improve things. But nothing was actually initiated or sustained and I moved on to other things.

A few months ago I was asked to spend a day in Australia at the City Melbourne (which is as Manhattan is to New York City, the officetower center of a vast metropolitan area). This time I was also asked to walk two processes—writing parking tickets (and collecting the money) and planning events (like concerts) in city parks. And it was a totally different world.

In each case a team of representatives from all of the departments and divisions involved had mapped the current process, identified the gap in performance, envisioned a better process, and started a series of PDCA cycles to close the gap. Everything was visual, showing clear responsibility for the performance of each value stream and its improvement across departments. I had the strong sense that the progress the teams were making could be sustained, with standardized work for managers and front-line workers.

The one problem that had arisen was that when a city becomes really, really good at ticketing every vehicle that overstays its parking time by more than five minutes, motorists become really, really good at not overstaying their time. As a result ticket revenues were falling even as other objectives for an improved value stream—better availability of parking spaces and a much better system for resolving disputes about broken meters and traffic officer behavior—were being achieved. This was another example of how every countermeasure designed to improve a value stream creates unintended consequences, which must in turn be countermeasured. It is a normal part of any improvement process.

My Melbourne experience, along with a number of recent calls I’ve gotten from state and local governments asking about lean thinking and the fact that governments everywhere are facing growing financial pressures at the same time voters expect better performance, have led me to think again about ways that lean principles and methods might be applied to the activities of governments.

Let’s start with what governments do. What value do they try to create? I think there are really three streams of work: enacting policies (laws) to regulate behaviors or deliver services; designing the enforcement and delivery mechanisms for these policies; and, operating these mechanisms on a continuing basis.

A simple example: A government (legislative plus executive) enacts environmental rules to address a perceived problem, a state agency writes detailed regulations and designs a mechanism for enforcement (e.g., granting permits), and the agency processes permits and proceeds against individuals and organizations who fail to comply with the rules. This is a vast activity, a substantial part of Gross National Product in every country, and one that seems to grow everywhere. (The Code of Federal Regulations in the United States, which records the detailed provisions of each federal law, now has more than 170,000 pages of text. State and local statutes and regulations contribute many times more.)

The first of these activities—enacting laws—is clearly the most problematic. What a wonderful thing it would be if every public discussion of an issue was in the form of an A3! (If Newt Gingrich could run for president in 2012 on the platform of “Six Sigma for Every Government Activity,” perhaps someone in the Lean Community—I’ll pass for lack of attitude or aptitude—should be running for president in 2016 on the platform of “A3 for All?”) The objective would be to describe what every public issue is about in one sentence, assess whether the problem needs to be addressed (or an opportunity needs to be seized), determine the root cause of the issue, detail the most promising countermeasures to test through PDCA, and identify what evidence will be accepted as to the success of the countermeasures.

Most Americans are familiar with the phrase that “the states are the laboratory of democracy” because of their freedom to try different countermeasures for the same problem. And this even more true of local governments. So there are three levels of government available for doing science. The problem is the will to do so.

The way things actually work is that all political debates start with solutions and work backwards to problems. And we can be sure that every solution is being promoted by someone with an emotional stake in the outcome (“save the planet” by regulating greenhouse gases) or with money to gain (for example, by advocating for mandating a new “green” activity in which they have a large financial stake). And sometimes these can be combined, for example mandating the addition of a minimum amount of ethanol in gasoline before it can be sold to the public, which may save the planet and certainly makes money for corn growers.

To be clear: We in the Lean Community have no standing on whether a government should regulate any activity or provide any service. This is a decision for citizens and their lawmakers. We can only make the humble suggestion that better decisions can be reached if the debate starts with a clear statement of the actual problem, followed by a structured process to identify and test countermeasures. For example, we have no voice in whether governments should license drivers. (Some libertarians probably think they shouldn’t; most people think they should.) But if governments are going to license drivers, we can suggest the important questions to ask: What is the best way to design and operate the drivers licensing process? How can we avoid wasting the time of the drivers and government employees while insuring that those who don’t have the skills or wisdom to be on the road are not licensed?

Yet when I look at governments at every level today I observe that most issues are not clearly stated, regulatory and service provision processes are not designed using lean principles, and regulations and services are not administered or provided using lean methods. So what can be done?

A3 for the policy-making process may take a while (although I’m always an optimist about the long run, as we demonstrate the power of this method in nongovernmental activities). So I wouldn’t wait around expecting progress in that area soon. But the prospect for improving the design of regulations and services is much brighter, as is the prospect for improving the actual conduct of regulation and the delivery of services. But, please, no “lean government” programs to be rolled by elected officials early in their terms, supported by a phalanx of consultants or internal staff teams committed to winning the “war on waste” in short order.

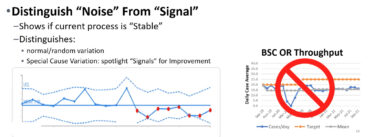

Instead the way ahead is to begin—any place will do—with experiments involving line managers and employee teams (and, yes, the people being regulated or served by the value streams as well). In each experiment make someone responsible for leading the development of an A3 that determines the current performance of a given value stream (for arresting vagrants or issuing building permits or whatever). Post the results – the work, after all, is the public’s business and is the business of the employees as well. Determine the gap in performance on whatever dimension is relevant: cost to the taxpayer, cost in wasted time to the person receiving the service, headaches for the government employees (or contractors) performing the work. Identify the most promising countermeasures. Run experiments with the countermeasures. Measure the results. Reflect on what to do next and, in particular, how to sustain positive results.

If any government at any level is willing to try this simple method for improving its value-creating processes, I will be delighted to take a gemba walk and help publicize the results. I’m sure they will be highly positive.