“Half my advertising budget is wasted – trouble is, I don’t know which half,” department store magnate and marketing pioneer, John Wanamaker, famously said. That estimate of waste is wildly optimistic, according to lean practitioner Brent Wahba, author of The Fluff Cycle. In the following excerpt he explains why much of what sales and marketing does is waste.

Chapter 6: Why Is He Picking On Us?

(Standing the heat because we own the kitchen)

In the continuous improvement world, there are raging debates about where in the organization to start. Some argue top-down while others prefer bottom-up. Maybe we should start in manufacturing and work our way back upstream to R&D? I’ve never heard anyone suggest starting in Sales & Marketing, though, and that’s too bad. We are part of many problems (note that I’m not blaming here) and very well-placed to start creating real solutions. Sales & Marketing is uniquely positioned between customers, Strategic Planning, Product Development, and Operations (Supply Chain + Manufacturing + Delivery + Service). Other than an occasionally very well-positioned CEO, nobody else in our company is at the center of our organization’s and market’s complicated universe. But for the sake of our cars sitting unprotected in the parking lot, however, we might not want to reveal to our co-workers that the universe really revolves around Sales & Marketing just yet.

Stepping back and thinking about it, shouldn’t all the departments in our company be working toward the same purpose and overall definition of success? Unfortunately, that definition gets broken up into lots of little related but disconnected bits as strategies are rolled out to business units, functions, departments, and eventually individuals. Who determines what customers value? Who owns the brand? What about customer satisfaction? And who is responsible for profit and growth? Everybody! But as a result of our self-focus (not to mention occasional self-importance), we sub-optimize our own function-specific processes and miss the big, important organizational improvement opportunities. Unless “selling” is our true constraint, creating a more effective selling process will often result in less happy customers and fewer sales long-term because we have now made more promises without the capacity in other areas (like order fulfillment) to meet increased demand.

There are reasons why our customers and co-workers don’t like us …

Sometimes it’s hard to truly understand, much less solve, a problem unless we can see it from multiple perspectives. The fact that 77% of companies report disconnects between Sales & Marketing functions (Aberdeen Research study) is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Most of the people in our companies, including our CEOs, often don’t understand what exactly we do in Sales & Marketing, or even why we do it. We rarely have defined processes that they can look at, and we speak in languages that they (not to mention our customers) cannot comprehend. They mostly think we either shoot from the hip, or are stuck in some parallel artsy-touchy-feely universe where logic, science, and measurement don’t apply. Titles like “Chief Loyalty Architect” don’t help much either.

Now from our perspective (or our interpreted customer perspective), we can’t get what we need from everyone else. “Why can’t we deliver on time?” “Why can’t the customer service reps be nicer?” And “Why don’t those geeks in R&D design better products at more competitive prices?” But at the same time, nobody else seems to get what they need from us either. “Why can’t we get an accurate sales forecast so we can stock the right amount of inventory?” “Why did someone promise the customer things we can’t deliver?” “Why can’t Marketing tell us what the customer requirements are before we are locked into a specific design?” And “How the heck do I increase ‘conversations’ and ‘mind share’ by 50%? I have no clue what those even are.” All expected, but not necessarily valid points of view depending on where we sit. And contrary to everyone’s beliefs, few have simple “just do it” solutions.

Real customers, on the other hand, don’t care AT ALL that Sales and Marketing are different functions, with different bosses, and sit on different floors. They don’t know who makes the service quality trade-off decisions, why their toaster doesn’t work as advertised, or what the holdup is for getting their kid a Kung Fu Grip Elmo for Christmas. They only care about solving their own problems and meeting their own needs with little thought and fuss. Unless they have some personal relationship with us (say with a specific salesperson or through some outstanding experience), all customers perceive is a blurry, monolithic company. Despite what we’ve been told, most of us don’t carry on deep personal relationships or even have real conversations with the vast majority of brands we interact with, and we really don’t want to either. Sorry, Tide – it’s not you, it’s me.

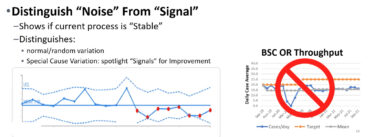

The department store magnate and marketing pioneer, John Wanamaker, is often quoted with “Half my advertising budget is wasted – trouble is, I don’t know which half.” Great insight, but wildly optimistic. If we think about creating value for customers to purchase and consume, most of what we do during the course of our regular activities of meetings, campaigns, sales calls, creative work, status reports, etc. is truly wasted effort. Office processes are typically < 20% value-added and managerial activities < 10%. Before you switch off your Kindle or Nook in a huff, though, I am not suggesting that we are lazy, stupid, or the root of all our organization’s evil. But think specifically about everything we do each day. Is each task truly moving the company forward toward success? Could things be much simpler to accomplish? How much time are we spending fixing others (or our own) supposed screw-ups? Would our jobs be much easier if everyone else simply did their jobs better? Waste adds up quickly and tends to spawn even more waste unless we proactively do something about it. And that brings us back to learning and problem solving.

Waste is a symptom of deeper, more complicated problems. If a multi-million dollar ad campaign has no impact on buyer behavior, or if a sales promotion leads to massive stock-outs and customer complaints, then those are big problems. They’ve generated lots of waste for our company, our suppliers, and our customers (who are now off telling all their Facebook Friends what a jerky company we are). What led to those problems is what we really need to solve – or else those types of events will happen over and over. The benefits of getting into the mud and solving our real problems are thus two-fold: 1) creating more value by better meeting customer needs with our products and services and 2) reducing work, rework, frustration, and cost – leaving us more time, resources, and mental capacity to focus on 1). When we find and fix the root causes of problems, we create better organizational alignment, increase our ability to influence our world, better understand where to invest our resources, and improve our capabilities to evolve faster than our changing world. Change is hard work, but it is impossible work unless we know what specific gaps we need to bridge and how exactly we are going to bridge them. But before we can do all of that, we need to learn a little about the even deeper cause of most of our problems: people and their complicated and often irrational human brains. In the meantime:

- Do our customers get what they need from us? What about others in our organization? Do we get what we need from them too?

- How much of our time is spent on truly value-added activities? Do we ever shake our heads and mutter “what the…?” over a required task?

- What types of problems keep us from being more efficient and effective?

- Does our creative work solve real problems and add value, or is it more for art’s sake and a shot at a CLIO?

For a deeper dive:

Brent Wahba is the author of The Fluff Cycle (And How To End It By Solving Real Sales & Marketing Problems) and the instructor of LEI’s workshops: Lean Fundamentals for Sales Organizations and Lean in Sales & Marketing (two days) .