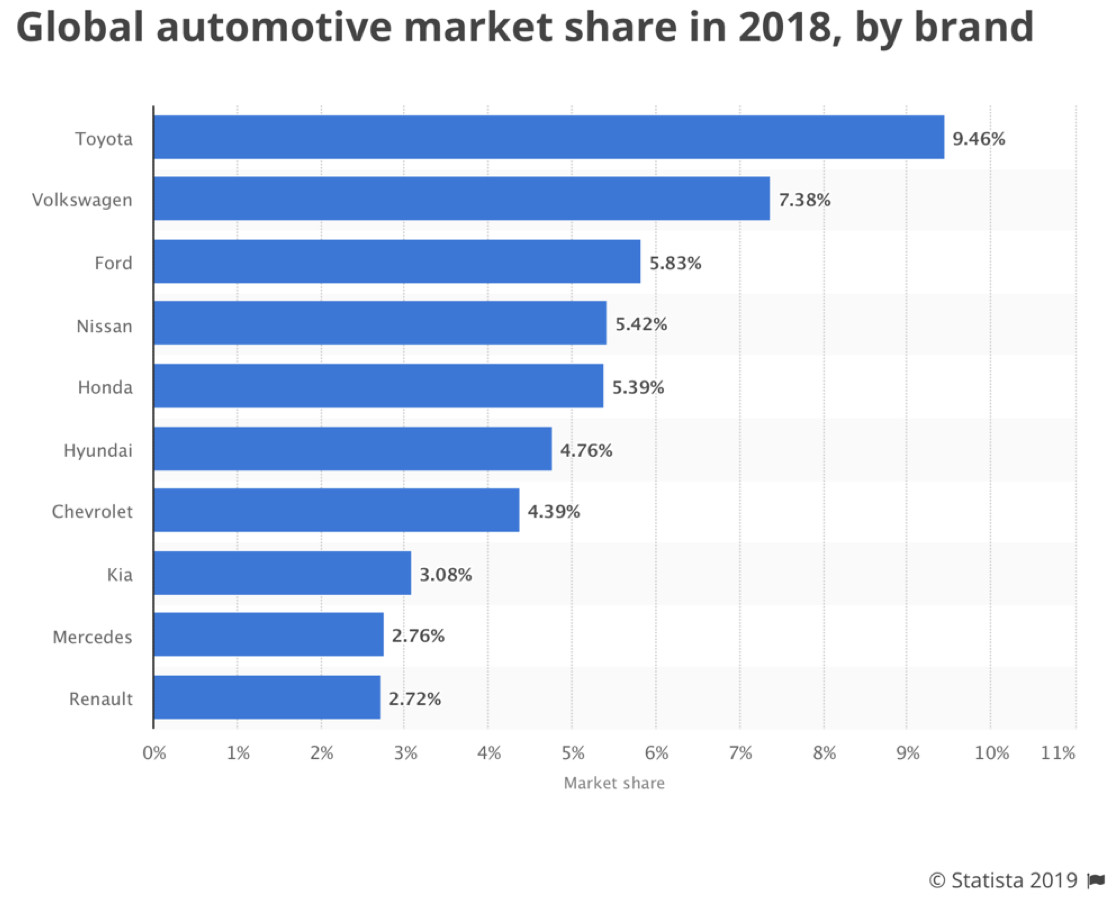

Lean is a product driven strategy. To make things clear, my understanding of lean is “try to figure out what Toyota does different and see if it applies outside of Toyota.” After 25 years of looking into it, I still find Toyota fascinating because they hold the top market share of their industry. This, with a recently reported profit margin of 8.93 %, close to a luxury boutique such as BMW of 8.22% during the same time.

I find this all the more fascinating since it grew steadily from a local, bankrupt automaker in the 1950s to the powerhouse it is today primarily through organic growth in a market dominated by the titans that were then GM, Ford and Chrysler. Toyota is holding to its principles and not indulging in the financial shenanigans that have brought low every other MBA-run company.

As a sociologist, I look at the strength of its company in its beliefs regarding people in both its goals and its organization. If people believe in the goals the institution pursues, find them worthwhile of their personal involvement, and agree to the methods the organization uses while finding them worthwhile of their personal engagement, then the group achieves wonders based on everyone’s willingness: insights, initiatives and inventiveness.

A fascinating aspect of the lean way of doing things is that “making money” is not our primary goal. Indeed, it’s not “the” goal. Toyota’s goal is to make a contribution to society by enhancing quality of life for people everywhere through manufacturing products. Making money is necessary to do so, but it’s a means, not an end. Two of the company’s guiding principles are:

- Dedicate our business to providing clean and safe products and to enhancing the quality of life everywhere through all of our activities.

- Create and develop advanced technologies and provide outstanding products and services that fulfill the needs of customers worldwide. (my italics)

This has far-ranging implications to understand what the company has done differently in the past, when it scaled up facing overwhelming opposition, and how it maintains its position currently. Toyota is not an efficiency-driven company. It’s a product-driven company.

A product is an object, material or digital, that allows its owner to solve a problem autonomously. product helps me to do something without help. There are always limits to that of course, as a product will need consumables, service and maybe even training to use it more efficiently. But the ideal product is one that I use effortlessly, grasping intuitively how it works without needing to talk to anyone else to make it work or maintain it. I’m autonomous.

Humans being humans, the value of a product lies in its practicality (fit in hand, fun to do the job), it’s robustness (lasts long and in varied situations) and its stylishness (I feel good owning it) – we’ve loved adorning ourselves with objects since the dawn of humanity, so no product can avoid a sense of esthetics – which corresponds to the culture of its users. A product also has a price and we look for value for money – a good deal.

Any product can be seen as the balance of service – what you can do with it, in your current context, without asking anyone’s help – and pain points – where the product pinches and frustrates you. Developing products people love (and will be loyal to) rather than just like or tolerate is a matter of maximizing the usefulness, taking away the pain points, and adding a “plus alpha” element that gives the product its own uniqueness. If you learn to do this better than competing offers, you’re away.

The lean approach to growing a solid base of loyal customers starts with product planning:

- A full range: Once a customer, you should find anything you want as your needs evolve within the company’s line-up, from the first car for your kids, to the family sedan, to the luxury coupé you want to treat yourself with just for kicks.

- A flow of products: For a certain range of customers, a product is never mature because not all the pain points (for instance, gas mileage) have been resolved and new value needs to be added as usages evolves (connectivity). Reinventing everything every time risks losing historical value while seeking new value, which is plain silly. By seeing every new product as an iteration in a maturity learning curve, engineers can ask “What do we keep? What do we change?” which leads to offering new benefits whilst not losing what makes the product and the brand great in the first place.

- A product comes out of a value stream: To touch people’s hearts, a product has to be smartly designed (grasping the hierarchy of what is truly important to customers), well-conceived (mastering the physical processes and materials that will make the product perform) with consistency (making every product as good as the engineer first dreamed it, although they come out of a boring production line and a complex supply chain).

In this perspective, someone has to capture what is really important for the next generation of customers and what techniques to use to deliver it – never easy in fast changing cultural markets with fast evolving technologies (well, some fast, some slow). The someone has to be very good at using physical processes to deliver that at the right level of quality every time. And then both these someones have to somehow find ways of doing so at reasonable cost to leave a profit once it’s sold at the market’s price.

Understanding these challenges lead to a unique way of looking at product development, with some very clear differences with the way new products are usually designed.

- Don’t translate customer wishes into a list of new features: Do listen intently to customers expressing their pain points and then think deeply about the value they’re not talking about because they take it for granted. Following customers’ advice is the best way to come up with a product they won’t buy. The real challenge lies in hearing the pain point and solving it in a way that makes the product even simpler to use, not adding more choices and more features – the product is there to make you more autonomous not more despondent. What do you keep, because this delivers the fundamental value? What do you change to adapt to evolving customer tastes and take away pain points? (a great example of this thinking can be found here)

- Understand what the production process can deliver easily: The performance of the product is your promise. Quality is whether you can keep your promise. Some production processes are far from the cliff edge, you can keep your promise easily with those. Others are close to the cliff edge: some of the parts produced are no good, which means that the process struggles. In order to design a killer product, the designer needs to understand very clearly what is easy to build and what is not.

- Change the process where you really need a new feature: Be prepared to adopt new technologies and change the process when you are intent on offering new value to customers, but be also aware a production process is… a production process: it can only handle one change at a time and is rather sticky because all steps are co-dependent, and people need to understand what the new gizmo does, which involves a lot of training and getting it right. This means choosing a few fights carefully.

With this in mind, we can see that 1) production is the testing ground for design, and 2) all the value for customers and costs for the company are set at the design stage. The unique lean insight is that having the most effective, sensitive and reactive plant in the world is essential to designing great products – but not just for the sake of having efficient operations. Kaizen makes sense in the light of creating the best test method for engineering decisions.

Like the drunk looking for his lost key under the lamppost because that’s where the light is, it’s easy to be mesmerized by Toyota’s flexible, hyper-efficient plants – the result of decades of looking for waste and engaging people into kaizen to keep the whole production process reactive. It’s easy to see how a traditional manager obsessed with making money will look at that and think “if I had such efficient delivery systems, I’d reduce my costs and increase my profits.” But the true secret to lean’s success lies in the building where no one is granted access: engineering. The real lean lesson for the world is “lean your production facilities to create a test system to develop ever better products.”

Lean’s trick to developing ever better products is to nurture “chief engineers.” (For more on this, please read the terrific new book Designing the Future by Jeff Liker and Jim Morgan.) Project management are typically held responsible for keeping deadlines. Product managers for the quality of the product and its success with customers. Here we have one special person who is expected to do both – and to negotiate with functional heads of department in charge of technical work. The second trick lies in constant kaizen in functional department to keep them at the top of their profession – achieved through go and see gemba walks, challenging and encouraging voluntary improvement initiatives by junior staffers. This is not a matrix per se as any person only reports to their department head. It’s creating tension to thread through silos by expecting:

- A fit-for-customer better design at every product that both captures de spirit of the times whilst retaining what makes the brand great.

- Continuous improvement and constant innovation in the specialist departments to support the chief engineers in coming out with “wow!” products.

What role does that leave for senior leaders in a product-driven company if all decisions are taken at the interface between chief engineers and department heads? Leaders create the conditions for success, which, in lean terms means:

- Picking the challenges in society that we need to respond to – such as the environment, globalization, digitalization or gender parity.

- Supporting careers to make sure the most talented people are given the opportunity and the training (mostly in the form of challenging roles) to give the best of themselves.

- Banging department heads together to ensure teamwork and that key problems in the company are solved from the point of view of customer value rather than functional glory.

- Invest in off the shelf devopment projects, mainly in new technologies, to explore what future capabilities chief engineers and department heads will need to stay in tune with the times.

This is a radically different vision of leadership, as we have developed in the book The Lean Strategy, because it is about making choices (seeking outcomes), not taking decisions on outputs (seeking outputs – decisions are taken lower in the organization within the scope of the choices made at the top). A lean strategy can therefore be summed up at senior leadership level as:

- Face the right challenges (and don’t do stupid stuff)

- Create a culture of “bad news first” and problem-solving to get every one’s participation

- Use improvement gains to free capacity to develop new products

- Keep products attractive by evolving in to make them fit with the spirit of the times (back to point 1)

To grasp lean thinking, start by changing how you look at a company. I started this piece with the traditional financial outlook of market share, growth and profitability. I should have started with the steady shift of the line-up to hybrid cars and Toyota’s challenge of no CO2 emissions for new vehicles. Don’t look at the accounts first, look at the product line-up: what is on the shelves right now, what is next on offer. Then see if customers reward these products with reasonable margins (and if the company doesn’t squander the cash if gets for its products in wasteful activities). A product is an emotion. Satisfied customers purchase again and tell all their friends. The only sustainable, profitable strategy is to aim to bring a smile to every customers’ face. Lean is all about learning how to do so.

Keep Learning:

- Don’t accept the status quo in product development. Join experienced developers and engineers who are redesigning product development systems to consistently create steady streams of ever-better products. Register today for the 2nd annual Designing the Future Summit, June 27-28, 2019: https://www.lean.org/designfuture2019