Once again Tesla is dominating the news cycle, this time by pulling a series of corporate all-nighters, makeshift workarounds, and frenzied finishing touches to reach their long-announced goal of producing 5,000 Model 3’s in one week. Never one to resist an opportunity to crack wise when it comes to dubious operations, LEI founder Jim Womack said of Tesla’s big production push:

“No other car company has ever had the need to do such a thing—in order to reach a promised production level by a certain date to keep investors happy and the founder’s reputation intact,” said James Womack, adding, “So Tesla is now a pioneer in temporary assembly, charting a course no one else will want or need to follow.”

Snap.

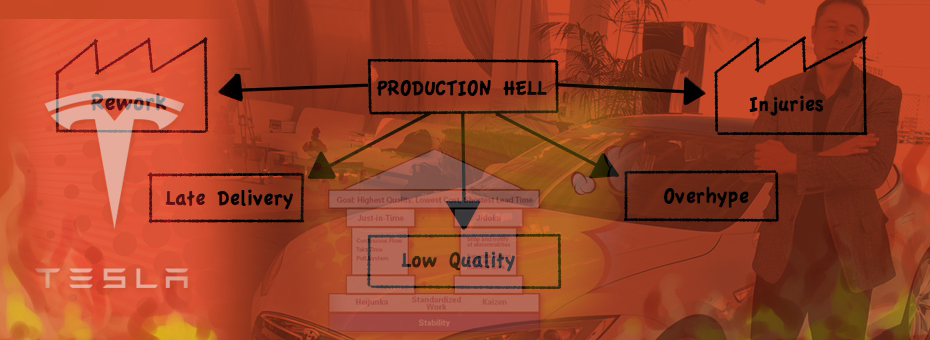

That said, what follows is a relatively schadenfreude-free roundup on Tesla. Tesla today serves as a highly-charged conduit for many a heated debate about the future of manufacturing, mobility, sustainability, innovation, modern business models, this year’s Red Sox team and, what, space travel. This piece examines Tesla though a lean lens. Lean thinking (or in some cases the absence of it) animates many of the key conversations about what can be learned from one of the highest-profile companies today. A brief overview of thoughtful pieces reflecting on Tesla reveal lessons such as:

- Innovation is about driving on the shoulders of giants

- Fix your problems before you start making things

- Accelerate production by leveraging your people rather than your robots

- Heroes cripple heroic campaigns

- Design your operations to optimize learning not outputs

Let’s look at each one a bit more closely:

Innovation Is About Driving on the Shoulders of Giants

Two years ago Mark Donovan debated the “Tesla Way” in a passionate debate with Jim Womack about the viability and legacy of Musk’s spectacular goals. Mark touted Tesla for creating “a sense of great urgency and ‘ludicrously’ high expectations,” noting that “The earth is the burning platform quite literally. Saving the planet and the human race is a pretty compelling call to action.”

Yet random bursts of genius are rarely sufficient to produce a successful venture as bold and ambitious as that which Musk is pursuing. Moreover, while Musk initially tapped into proven lean knowledge in his early launch by partnering with Toyota for advice and even locating his primary factory in the very building that Toyota launched NUMMI, the more that Tesla approached production showtime, the more it shrugged off lessons from others. Noting that Tesla’s initial approach was broadly consistent with lean thinking, Womack said, “By selling vehicles directly to customers and keeping in continuous touch with every customer through the internet, Tesla proposed to create more value with less resources, the essence of lean.”

However, as Tesla ramped up to high volume mode, it veered far from proven operating systems (hello TPS) that demonstrated how to produce high volumes of vehicles with high quality. Instead it increasingly rested on racing at rocket speed to substantiate the wild claims of its chairman. Womack suggested that this business model was not up to the job of scaling to realize bold predictions made by Musk: “The Tesla Way is to go fast (“Let’s try ludicrous mode!”) and hope that genius and adrenaline can compensate for the lack of planning and stability. But I would advise going slower and getting the job done right the first time in accord with the Toyota Way.”

Fix Your Problems Before You Start Making Things

Many articles have detailed the heroic countermeasures (could somebody find Elon some PJ’s for his nights sleeping on the production floor?) Tesla has devised to hit its ludicrous production targets. Yet the question of how well they have scrambled to survive is less important than the one about identifying the source of its problems. The key time to ensure quality production on a scale such as the Model 3 is upstream—at the very beginning, says Jim Morgan in The Road to Production Hell is Paved with Lack of LPPD:

“TPS is an incredibly powerful manufacturing system. But once you are at launch, your tools, fixtures, processes, part designs, interfaces, and requirements – they are all done. The degrees of freedom remaining for the manufacturing folks are now just a small fraction of what they were during the earlier development process. Front loading your development process has long been a fundamental tenant of lean development. And the front end of the development process is where rapid learning cycles through targeted experimentation should take place. Not during the launch, let alone production. While problems may be rich learning opportunities, when it comes to launch the best problems are the ones you never have.”

Accelerate Production by Leveraging Your People Rather Than Your Robots

Earlier this year Jeff Liker questioned the power of Musk’s essentially mechanistic approach towards his production system, taking issue with Musk’s claim that “the factory is going to be the product that has the long-term sustained competitive advantage.” And not just any factory—but the most automated factory, with the most high-end robots know, that would feature the most sophisticated robots known to man (or robots). And in his dream of a “lights-out factory” Musk was not merely harkening back to previous dreamers, but he was under-valuing the role of people as part of this socio-technical system.

“What Elon Musk is missing is exactly the point that has made Toyota so successful. Toyota’s living system approach is exactly what has been missing from Musk’s mechanistic view and needs to be at the center of his vision, not as an occasional response to a crisis. Toyota is a learning organization with a long memory. In 1979, Toyota launched the Lexus LS400 with the most advanced automation in the company at its Tahara, Japan, plant, including robots in assembly doing jobs normally done by people. Sales were below expectations and the plant was underutilized. Toyota’s reflection was that the high capital costs were fixed and could not be adjusted to match demand.”

The company however trudged forward adhering to a simple principle that production equipment would be “simple, slim, and flexible” to work in harmony with people. The people on the line are expected to be the source of learning and improvement; innovations can be automated only after they have been proven to work manually.

As Jeff Rothfeder writes in Fast Company, Toyota is doubling down on its people as the source of continuing innovation in the manufacturing process. The thinking behind TNGA, Toyota’s TPS 2.0, is that innovation emerges from low-tech experiments and problem-solving on the manufacturing line, and learning is captured and then operational-ized from this work:

“Among the more compelling experiments underway in Georgetown is a training exercise meant to infuse the TNGA idea that automation should solely grow organically out of human innovation. To this end, assemblers were given a karakuri assignment–a lean management drill that requires workers to build a Rube Goldberg-inspired contraption that operates under its own force to improve a workspace activity. One team is reengineering the flow rack, the ubiquitous stand next to each assembly station that holds the parts needed for the local task. Currently, as shelves are emptied, workers have to manually set them aside and then replace them with a full bin of parts. The “modernized” version will instead rely on a combination of springs, ropes, and weights to navigate this task after a button is pressed. When this decidedly low-tech device is perfected, Toyota plans to use the prototype as the blueprint for a robot to emulate the process.”

Matt Savas’s article on karakuri elaborated on this idea: “Karakuri demonstrates that Toyota’s working currency is brainpower, grown through rigorous problem-solving and mentors who challenge their students. The wallet takes a backseat to the brain. Toyota’s response to the challenge of increasing kaizen capability wasn’t to find smarter people or more clever machines. Instead, it was to 1) make kaizen more accessible by simplifying engineering and 2) develop people to make work better using the engineering.”

Heroes Cripple Heroic Campaigns

While American business culture is addicted to the heroic role played perfectly by Elon Musk, most superior lean companies thrive because they are led by humble individuals who see their job as stabilizing and improving the core elements of a business—people, process and purpose. Womack notes that the key job of a hero is to dive into a chaotic situation and quickly impose some sense of order. But organizations thrive by restoring basic stability and installing what he calls “farmers”, or value-stream-managers, who continually ask three questions: Is the business purpose correctly defined? Is action being taken to create value, flow, and pull in every step of the process while taking out waste? Are all of the people touching the process actively engaged in making it better?:

“Why do we have so many heroes, so few farmers, and such poor results in most of our businesses? Because we’re blind to the simple fact that business heroes usually fail to transform businesses. They create short-term improvement, at least on the official metrics, but it either isn’t real or it can’t be sustained because no farmers are put in place to tend the fields. Wisely, they move on before this becomes apparent. Meanwhile, we are equally blind to the critical contribution of the farmers who should be our heroes. These are the folks who provide the steady-paced continuity at the core of every lean enterprise.”

Design Your Operations to Optimize Learning Not Outputs

Perhaps one of the most important underlying themes of the unfolding Tesla story has to do with the idea of learning versus optimization. There’s no doubt that Elon Musk is a genius, and many of the doubtiest Tesla doubters rave about the delights of actually driving one. And yet the ongoing woes of the company reveal a built-in aversion to reflection, learning, and adaptation given the premium placed on a brilliant founder racing around fixing an ongoing string of catastrophes. The Toyota Production System, and lean, are about placing self-reinforcing system improvement above the unsustainable practice of eternal point optimization.

The recent book The Lean Strategy argues that Toyota tools serve as frames for learning that enable individuals to better understand a complex situation and find a better way of tackling a problem. In what is known by many as the “Thinking Production System,” point optimization (which rarely leads to deeper systematic gains) takes a back seat towards seeing problems as things to “fix” rather than opportunites to learn. “The TPS is, in essence, a vast mental scaffolding structure to teach people to think differently, working on the assumption that, as John Shook says, you don’t think yourself into a new way of acting, but you act yourself into a new way of thinking,” says Michael Balle, “The TPS defines challenges and exercises to help you understand your own business differently. It’s a learning method, not an organizational blueprint.”

As Michael Balle says in Why Toyota is Still My North Star, “Sadly, while I’m stunned by Toyota’s technical prowess as described by Bertel Schmitt and Ed Niedermeyer I keep having conversations with lean directors in large global companies who want to know how to further deploy their lean programs with their roadmaps, kaizen counts, savings, penetration rate (I kid you not) and other measures of process optimization. I keep asking myself: where did we go so wrong? How could we turn radically new management method based on seeking dynamic performance improvement through the intermesh of product and production engineering into corporate programs for static optimization of existing processes?”

I’d like to close with one question: what lean lessons do you think can be gleaned from Tesla?